Tasmanian Tiger No Sheep Killer

Thylacine Not a Sheep Killer – No “Jaws” for Alarm

The Tasmanian Tiger (Thylacinus cynocephalus) became extinct in 1936 when the last known living specimen died at Hobart Zoo. Scientists believe that the Thylacine had been extinct in mainland Australia for some 2,000 years but populations survived in remote parts of Tasmania up until the early 20th Century. One of the reasons given for this apex predator’s decline was that it was hunted extensively by farmers and land owners in a bid to reduce attacks on their sheep.

Tasmanian Tiger

However, the Thylacine may have been wrongly accused of killing sheep, a new study published in the Zoological Society of London’s “Journal of Zoology” has found that the “tiger” had such weak jaws that its prey was probably no larger than a possum.

Lead author, Marie Attard of the University of New South Wales (UNSW) Computational Biomechanics Research Group stated:

“Our research has shown that its rather feeble jaw restricted it to catching smaller, more agile prey. That’s an unusual trait for a large predator like that, considering its substantial 30 kg body mass and carnivorous diet. As for its supposed ability to take prey as large as sheep, our findings suggest that its reputation was a bit overblown.”

The Thylacine, otherwise known as the “Tasmanian Tiger” was probably a hunter of much smaller prey, other marsupials and flightless birds being cited as typical prey examples, but not the introduced livestock such as sheep, goats and young cattle. A generous bounty was paid for every dead Thylacine and this hunting and trapping led to the rapid extinction of an animal population that was already under considerable stress due to loss of habitat and indigenous prey.

Author Marie Attard with a Thylacine Jaw

Picture credit: Marie Attard

The picture shows Marie holding the skull of a Thylacine, note the wide gape of this predators jaws.

Marie added:

“While there is still much debate about its diet and feeding behaviour, this new insight suggests that its inability to kill large prey may have hastened it on the road to extinction.”

Despite its obvious decline, it did not receive official protection from the Tasmanian Government until two months before the last known individual died (the Hobart Zoo Thylacine).

Advanced Computer Modelling Techniques

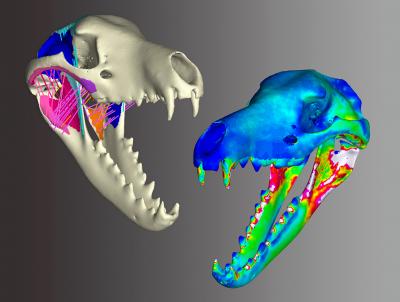

Using advanced computer modelling techniques, the UNSW research team were able to simulate various predatory behaviours, including biting, tearing and pulling, to predict patterns of stress in the skull of a Thylacine and those of Australasia’s two largest remaining marsupial carnivores, the Tasmanian devil and the spotted-tailed quoll.

The Thylacine’s skull was highly stressed compared to those of its close living relatives in response to simulations of struggling prey and bites using their jaw muscles. This indicates that tackling sheep was not on the Thylacine’s menu – the fear of a “tiger” attacking a flock of sheep would be unfounded. There would be no “jaws” for alarm.

A Computer Generated Image Showing the Stress Levels on Thylacine Jaws

Picture credit: Marie Attard

The picture shows the digital stress tests revealing weakness (red/white areas in right-hand image) in the Thylacine jaw.

Director of UNSW’s Computational Biomechanics Research Group, Dr Stephen Wroe stated:

“By comparing the skull performance of the extinct Thylacine with those of closely related, living species we can predict the likely body size of its prey. We can be pretty sure that Thylacines were competing with other marsupial carnivores to prey on smaller mammals, such as bandicoots, wallabies and possums.”

A Stuffed Tasmanian Tiger on Display in a Museum

A Thylacine is included in the Australian mammals part of the gallery (Senckenberg Museum). Picture credit: Everything Dinosaur.

Picture credit: Everything Dinosaur

It seems that the bounty on the Thylacine may have been unjustified, a case of “shoot first and think later” as a member of the Everything Dinosaur team commented.

Dr Wroe added:

“Especially among large predators, the more specialised a species becomes the more vulnerable is it to extinction. Just a small disturbance to the ecosystem, such as those resulting from the way European settlers altered the land, may have been enough to tip this delicately poised species over the edge.”

The Hobart specimen died on September 7th 1936, this date is commemorated in Australia as the National Threatened Species Day, helping to highlight the plight of other endangered species on the continent. Ironically, there are from time to time reports of sightings of Thylacine-like animals both on the Australian mainland and in Tasmania. Many cryptozoologists believe that small populations of this pouched predator may still survive in remote parts of the Australian outback. A few fuzzy photographs and 8mm film footage exist, taken by people who claim to have seen a strange animal, but as yet there has been no real evidence to suggest that the Thylacine is still with us.

To view models of extinct animals: CollectA Popular Range of Prehistoric Animal Models.

Everything Dinosaur acknowledges the assistance of a University of New South Wales media release in the compilation of this article.

The scientific paper: “Skull mechanics and implications for feeding behaviour in a large marsupial carnivore guild: the thylacine, Tasmanian devil and spotted-tailed quoll” by M.R.G. Attard, U. Chamoli, T.L. Ferrara, T.L. Roger and S. Wroe published in the Journal of Zoology.