New European Meat-eater Discovered – One Lump or Two?

Early Cretaceous Hunchbacked Hunter from Spain

A discovery of a bizarre theropod (meat-eating dinosaur) announced in the scientific journal “Nature” has led scientists to re-examine current theories about the evolution of feathers and the dinosaur/Aves link. This new genus of predatory dinosaur with bony bumps on its arms and a strange lump on its back may provide evidence that feathers evolved earlier than previously thought. The dinosaur has been named Concavenator corcovatus.

This new species is just one of a number of amazing Early Cretaceous vertebrate fossils discovered at the Las Hoyas site in Spain, in the Iberian Mountain Ranges of Cuenca Province. Due to the exceptional state of preservation, Las Hoyas, like the Liaoning area in China, is one of the world’s most important fossil sites for understanding the transition from dinosaurs to birds.

Palaeontologists have unearthed from the finely grained sediments, many thousands of well-preserved fossils of birds, most of these have been found in slightly younger strata than the rocks from which this new theropod comes from, however, this new species of meat-eating dinosaur with its strange arms may shed new light on the dinosaur/aves relationship.

Concavenator corcovatus

The new species has been named Concavenator corcovatus (the name means “humpbacked hunter from Cuenca”), although just one fossil specimen is known, it is remarkably complete and represents (we think), only the second case of a theropod dinosaur from the Calizas de la Huerguina Formation. In fact despite the superb quality of other vertebrate specimens recovered from Las Hoyas, very few fossils of Dinosauria have been found at the site.

Perhaps the most famous dinosaur discovered in this region of Spain is Pelecanimimus polydon, the first theropod dinosaur to be found. P. polydon is believed to be an ornithomimid, a fast running dinosaur that some scientists have suggested may have fed on fish.

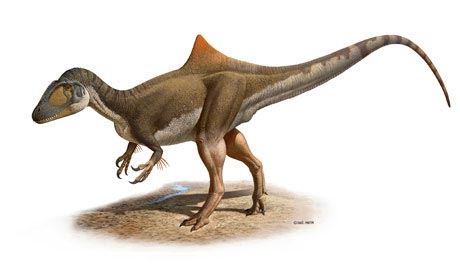

Concavenator was definitely a hunter, measuring about 4 metres long, this agile dinosaur may have preyed upon other small vertebrates that shared its environment. It has been dated to around 130 million years ago (Barremian faunal stage). Although, the Las Hoyas area today is a hot and arid area, back in the Early Cretaceous the site was a lush, tropical, wetland paradise with many rivers leading to a large, shallow lake.

An Artist’s Interpretation of Concavenator corcovatus

Picture credit: Raul Martin

A European Hunter

The discovery of a new type of European meat-eating dinosaur is exciting in itself, but what has got the researchers really in a flap is that this new specimen may shed further light on the evolutionary link between the theropods and the birds we see around us today. For palaeontologist Francisco Ortega of the National University of Distance Learning in Madrid, who led the research, the strange bumps on the forearms could provide evidence of feathers in a dinosaur belonging to a branch of the dinosaur family tree not known for their feathered forms.

To view a model of this dinosaur and other dinosaur models: PNSO Age of Dinosaurs Models.

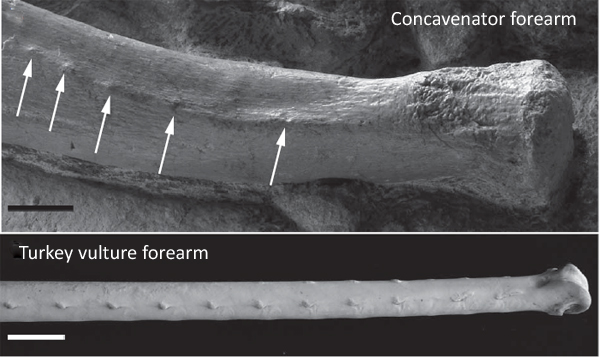

The research team think that the bumps and nodes on the forelimbs may have been part of structures that anchored the quills in proto-feathers to the arms of Concavenator.

Feathered Theropod

A feathered theropod is not that unusual, for example, a number of types of meat-eating dinosaur are believed to have been feathered, but they all belong to one particular clade within the Sub-Order Theropoda – the Coelurosauria. This part of the theropod family tree contains clades such as Maniraptoriformes and the Dromaeosauridae types of dinosaur such as Bambiraptor, Dromaeosaurus and Velociraptor that many scientists now believe were feathered.

Analysis of the fossilised skeleton of C. corcovatus suggest that this dinosaur was not a member of the Coelurosauria, but more akin to an allosaur (Allosauroidea), a clade of dinosaurs not known for their feathers. The allosaurs are in essence a different branch of the theropod family tree.

Commenting on the research, Professor Mike Benton, of the department of vertebrate palaeontology at the University of Bristol, (United Kingdom) stated that the bumps on Concavenator’s arms:

“look exactly like the insertions of rather massive flight feathers on bird wings.”

An Enlarged Image of the Foreman of Concavenator compared to an Extant Bird Species

Picture credit: Nature

If Francisco and his co-workers have interpreted the “bumps” correctly, this implies that dinosaurs showed feather-like structures much earlier than previously thought. Unless the development of proto-feathers within members of the Allosauroidea is evidence of convergent evolution (the acquisition of the same biological features by unrelated lineages), this Spanish based research suggests that the common ancestor of both the Coelurosauria and the Allosauroidea may have sported primitive feathers.

Evidence of “bumps” on the ulna bones of dinosaurs have also been discovered. In an analysis of Velociraptor material; a sequential line of bumps and nodes was found along the ulna, these too were interpreted as being evidence to suggest that Velociraptor was feathered, although no fossils indicating feather impressions have been associated with this genus.

To read more about the analysis of the ulna of Velociraptor: Evidence of feathers on the arms of Velociraptors.

Ortega went on to suggest that a member of the Neotetanurae (new stiff-tailed theropods), the common ancestor of both these two predatory dinosaur branches:

“could have been feathered.”

Feathered Dinosaurs

This hypothesis is really pushing back the date at which the first feathered dinosaurs may have evolved. The Neotetanurae are associated with the Middle Jurassic such as the Bajocian and the Bathonian faunal stages (170 to 160 million years ago), many millions of years before the Coelurosauria are believed to have evolved.

Francisco Ortega added:

“We’re pushing back the time when bird-like structures appear.”

The scientists have been puzzling over another aspect of this, most definitely cursorial (despite the potential feathers) dinosaur, it had a strange hump on its back, The eleventh and twelfth vertebrae stick out about twice as far from the animal’s body as the rest. This does not seem to be pathology (evidence of an injury or disease), but some sort of support for a structure, like a hump or a fin of some kind. Unlike the long flowing sails of Spinosaurus or indeed the extravagant appendage of the Ourannosaurus, C. corcovatus seems to have a short crest.

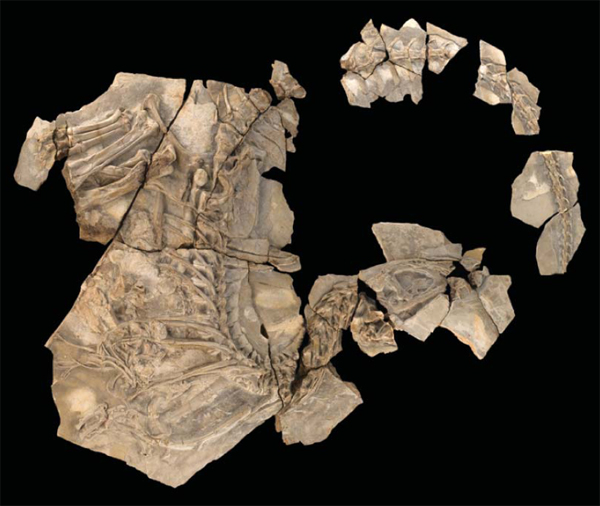

The Prepared Fossil Skeleton of C. corcovatus

Picture credit: Nature

The picture shows the prepared fossil skeleton of Concavenator, displayed showing the typical “death posture” of a meat-eating dinosaur. As the carcase lies on the surface undisturbed, it dries out and the tendons in the neck and tail contract leading to an arching effect as the tail and head bend towards each other.

Scientific opinion is divided as to what the crest could have been used for, perhaps it was used for visual communication between individuals or members of a hunting pack, or it could also have been used to help this relatively small dinosaur to regulate its body temperature (thermo-regulation). If this dinosaur was feathered, or at least partly feathered; the feathers could have helped insulate the animal and keep it warm, aiding the thermoregulation offered by the crest. Alternatively, if the crest was predominately used for display then the feathers on the arms may also have helped in the visual displays.

One thing is for certain, until more fossils of this type of dinosaur are found, the role of the crest will remain disputed, however, Professor Benton summed up this new genus very concisely when he stated that”

“We can’t say anything about it other than: isn’t it weird?”

This new dinosaur discovery poses another question in relation to bird biology according to Professor Benton:

“What is the range of feather-like structures among dinosaurs which don’t exist in any birds today?”

The bumps on Concavenator’s arm evoke those on feathered birds, but may have been anchors for other structures such as bristles built from keratin, the same protein that makes up feathers, fur and nails. There may be other evolutionary dead ends like strange bumps on the arm of this Spanish dinosaur among dinosaurs that modern-day bird biologists would like to know about, the Professor added.

The research leader Francisco Ortega agrees that there is probably a great deal more to learn about the evolutionary relationship between Dinosauria and Aves.

He went on to state:

“We’re going to have to conceive of more dinosaurs as being more like birds. Most allosaurids are depicted as plodding animals, quite distant from birds. What this tells us is that they may have included more bird-like species too.”

The scientific paper: “A bizarre, humped Carcharodontosauria (Theropoda) from the Lower Cretaceous of Spain” by Francisco Ortega, Fernando Escaso and José L. Sanz published in the journal Nature.