Special Silver Jubilee for Royal Tyrrell Museum (Alberta, Canada)

Royal Tyrrell Museum in Drumheller Celebrates 25 Years

This weekend marks the 25th anniversary of the opening of the Royal Tyrrell Museum in Drumheller (Alberta, Canada), a museum dedicated in the main to dinosaurs and the specimens to be found in the amazing strata of the Canadian province of Alberta.

Royal Tyrrell Museum

The Tyrrell opened on September 25th 1985, it did not get the “Royal” status until 1990, this museum, adjacent to numerous outcrops and exposures of Upper Cretaceous strata, has done much to put Canada “on the map” as it were when it comes to palaeontology and related disciplines.

Don Brinkman, Director of Preservation and Research at the museum, recalls that in the early 1980’s scientists began working on an extensive horned dinosaur bone-bed, at the time a very ambitious excavation. The project to build a museum in the area of Drumheller was already underway when he joined in 1982.

He recalled:

“We had three years for designing the building, building the building and collecting the specimens. Looking back it was phenomenally ambitious, but we were all very young and we had no idea that a project [of that size] should take ten years.”

At first the staff worked out of offices in Edmonton, but the first museum director, David Baird decided that to work best, the scientists needed to be in and amongst the fossils, so the young Don Brinkman found himself working in a converted Co-op grocers in Drumheller, with colleagues and facilities scattered around the town. From the beginning, he knew that working for the “Tyrrell” would be very different.

As the Royal Tyrrell staff emphasise, this museum was never going to be simply a collection of fossilised bones. The museum is named after the famous Canadian geologist Joseph Burr Tyrrell (1858-1957), who discovered the skull of Canada’s first meat-eating dinosaur (Albertosaurus) whilst prospecting for coal on behalf of the Geological Survey of Canada. The name is pronounced with the onus on the first syllable, as in “squirrel”.

Discussing the culture and ethos of the museum, Don added:

“It was decided that the focus would be on palaeobiology. We wanted to understand the animals as they were living. The foundation of palaeobiology is the fossil, but now we’ve taken an object and created a world around it.”

He admits it wasn’t a widely followed approach:

“It was viewed as wishy-washy, because there hadn’t been the scientific rigour for that kind of observation. One of the most important things over the museum’s 25 years has been the development of this type of approach as rigorous science.”

This philosophy explains why today, although most of the galleries feature dinosaurs, there are also extensive exhibits on life on Earth over the last 300 million years or so. The museum has experts on dinosaurs, and also geologists, palaeobotanists, and other specialist all helping to take care of over 110,000 fossil specimens and over the twenty-five years of the museum – ten million visitors.

When people visit the museum, as Don Brinkman says:

“They are seeing dinosaurs in the context of where they lived and how they interacted.”

We at Everything Dinosaur have been lucky enough to visit the museum on several occasions. We have worked on some of the dig sites and helped in the huge fossil store rooms, indeed we would wager that there are a number of new species awaiting to be discovered, once the staff at the museum get round to studying all the fossils that have been placed with them after their excavation.

The museum really is an amazing place and very user friendly, full of helpful staff. It is one of our favourite museums in the world.

Dr Don Brinkman, Preservation and Research Director at the Royal Tyrrell Museum, is delighted to preside over the 25th anniversary of the museum’s opening. It is difficult to say exactly what the exhibit is in the background, but we assume it is a specimen of Albertosaurus sarcophagus, the same type of dinosaur the Joseph Burr Tyrrell discovered.

A number of special events and programmes are planned to mark the silver jubilee. Twenty-five specimens form part of a special exhibition that tells the story of the history of the museum, one exhibit for each year of the museum’s existence. Together they tell the story of Royal Tyrrell, chronicling the stories, the people and the events.

One of the stars of the show is the exquisitely preserved T. rex fossil known as “Black Beauty” (TMP 81.6.1), one of only two T. rex fossils found in Alberta. The fossil specimen is jet black and represents about 25% of the entire animal, including a substantial amount of cranial material. The jet black colour of the fossil is a result of manganese deposited by local groundwater penetrating and coating the fossil.

Senior science educator Megan McLauchlin explains that the colour is not the only thing that is special about this particular tyrannosaur fossil. It is a fossil of a sub-adult animal, she went onto state:

“When you’re studying fossils, you really want a range of ages in the specimens.”

The specimens in this special exhibit tell uniquely local stories of scientific advancement. The block of duck-billed hadrosaur eggs and embryos found at Devil’s Coulee in southern Alberta, for example, featured a new species of Hypacrosaurus, and helped to advance theories about how these dinosaurs cared for their young and about population dynamics.

The braincase of the Troodon, a small, meat-eating dromaeosaur, helped convince Dr Philip Currie, one of the world’s most famous palaeontologists, of the link between dinosaurs and birds.

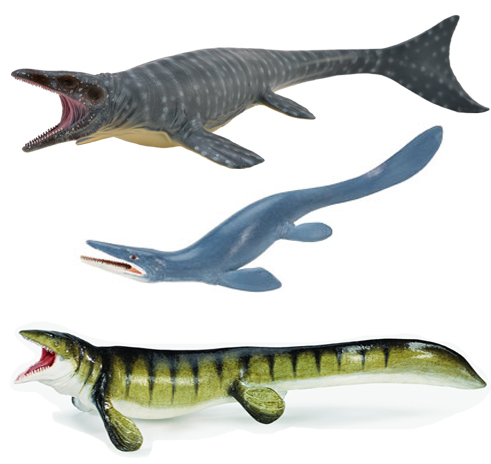

The almost complete mosasaur skeleton, a monstrous marine reptile, included its last meal of sea turtles and large fish, a key discovery about its diet.

Example of Mosasaur Models

To view a model of a Mosasaurus, marine reptile figures and dinosaur models: Safari Ltd. Wild Safari Prehistoric World.

And that’s the secret, McLauchlin says, behind Alberta’s success in the world of palaeontology.

She added:

“We had not only great conditions for the dinosaurs to live in, but also great conditions for them to die in and then be buried.”

The parched, streaked cliffs behind her may not look like the forested, riverine plain of the Centrosaurus herd, but she says you just have to know how to read the rocks. White sandstone indicates the fast-moving waters of oceans and rivers; darker mudstone represents slower moving swamps and lakes; black coal was once deep plant growth; and ironstone, look for the petrified wood chunks, speaks of a swampy forested environment.

And those cliffs are still talking, as Dr Brinkman says:

“We keep going back to places like Dinosaur Provincial Park because there’s high erosion there and there’s lots to be found. Last year was one of our best years yet in terms of significance of specimens.”

Much of what we now know about the Late Cretaceous, particularly the Campanian faunal stage is down to the scientific projects and field work carried out by Royal Tyrrell staff and volunteers. We wish them the very best for their 25th anniversary celebrations and perhaps we can get over to Alberta again ourselves soon.

Everything Dinosaur Team Members at a Dig Site (Royal Tyrrell Field Work)

Picture credit: Everything Dinosaur

Everything Dinosaur team members doing their bit for the Royal Tyrrell collection. The pictures shows team members taking a break during a hadrosaurine excavation.