New Pterosaur Discovery Announced (Despite the problem with the Car Filler)

Discovery of new Cretaceous Pterosaur Announced

The latest edition of the scientific journal Palaeontology contains a paper on a new type of pterosaur, written by a team of researchers from Portsmouth University. This new type of flying reptile has been named and described, despite the compressed nature of the specimen and the fact that car body filler was used in the excavation to hold all the fragments of bone in place.

New Pterosaur Discovery

The animal has been named Lacusovagus magnificens (means magnificent lake wanderer), a flying reptile with an estimated wingspan of 5 metres and standing as tall as a grizzly bear. Although, a very imposing creature, the hollow bones and other anatomical adaptations for flight would have made this animal extremely light, perhaps weighing less than a 12 year-old child.

Lacusovagus magnificens

The fossil was discovered in the Araripe Basin, in north-east Brazil. This specimen is providing a fresh insight into the evolution and spread of Pterosaurs as this particular creature’s nearest relatives originate from China. The skull material is the most important part of the fossil, allowing palaeontologists to establish taxonomic relationships between different species and genera. Lacusovagus is the biggest Pterosaur of this type found to date, most of the Chinese specimens had wingspans of less than one metre.

An Illustration of Lacusovagus magnificens

Picture credit: Mark Witton/University of Portsmouth

This toothless pterosaur (the technical term for flying reptiles – the name means winged lizard), has been dated to approximately 115 million years ago (Aptian faunal stage), but the pterosaur fossil record dates back much further into the Triassic. These animals were the first vertebrates to develop powered flight. Unfortunately, the remains were first discovered were so fragile that it was decided to protect them by covering them with car filler. This certainly helped strengthen the fossil and aided the recovery process but the preparation of this specimen has proved to be extremely difficult as researchers tried to remove filler so that they could study the fossil bone.

The Car Filler Problem

The car filler was so difficult to remove, that the research team had to make do with examining the small pieces that were exposed out of the limestone and car filer matrix and rely on CAT scans of the block of stone to reveal more internal detail.

Mark Witton, the University of Portsmouth academic who identified the specimen, broke several tools trying to cut through the filler, unfortunately, this is not the first time an inappropriate material has been used in the fossil preservation process. Another Brazilian fossil, this time of a dinosaur from strata dating from the the later Albian faunal stage proved extremely difficult for the scientists to research properly. A skull of an unknown type of dinosaur was researched by British palaeontologist David Martill, also from the University of Portsmouth. Unfortunately, the 80 cm skull had been doctored, with bits of filler and plaster added to make the specimen look more exciting and hence more valuable. So frustrated by the “extra bits” added by the finder hoping to make more money from the sale, that the team reflected their angst in the naming of this particular dinosaur – it was called Irritator.

Commenting on the preservation status of this new pterosaur find, Mark Witton stated:

“The specimen was quite fragile so the guys who were collecting it – probably quarrymen – very sensibly decided to put a large slab of limestone underneath to strengthen it. Unfortunately, they used car body filler as the glue. The infernal car filler was a real cow to get through. I don’t know how many tools I broke trying to cut it”.

Unlike the Irritator case, Mark does not believe that these people intended to defraud.

“I’m sure it was used with the best of intentions but the person who did it perhaps hadn’t thought it through,” he added.

Interpreting the Fossil Specimen

Further problems in interpreting the remains were encountered because the skull was misshapen and compressed. The distorted skull fragments make interpretation very difficult, the position of this fossil in the matrix was quite unusual and this added to the preparation problems.

“Usually fossils like this are found lying on their sides, but this one was lying on the roof of its mouth and had been rather squashed, which made even figuring out whether it had teeth difficult.”

The skull of this particular flying reptile was much wider than is usual for pterosaurs and Mark Witton has suggested that it had a wide throat, which would have vastly increased the range of prey available to it. pterosaurs are widely thought of as fish-eaters, but he said it was likely that the new species would have eaten small dinosaurs, which it would have swallowed whole. The toothless beak and wide throat would have enabled it to catch and swallow various prey animals – perhaps moving in groups across the fern plains flushing out lizards, mammals and even small dinosaurs a bit like the lifestyle of the Marabou stork in Africa.

This particular habit has been proposed for pterosaurs before. In an earlier blog article we reported on Mark Witton’s work on the Late Cretaceous pterosaur Quetzalcoatlus and speculation about these extremely large creatures having a more terrestrial lifestyle than previously thought.

To read this article: Getting stalked by a flock of Quetzalcoatlus.

For Mark and his team, fossils such as this one from Brazil are providing new insights into these amazing animals.

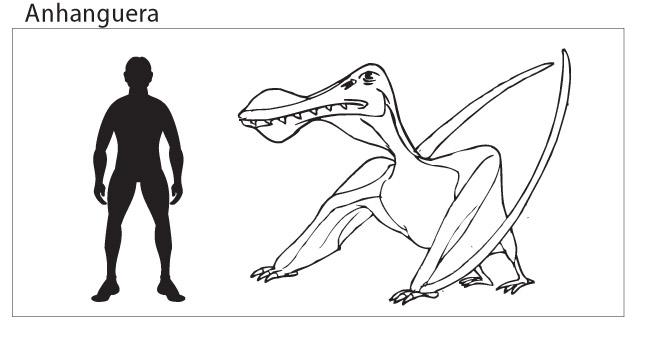

Brazil is becoming quite famous for pterosaur finds, a number of new genera have been identified from the Santana Formation of Brazil, a series of rock strata dating from the Early Cretaceous. Both toothless and toothed types of pterosaur have been found in the upper layers of the Santana Formation, including the toothed flying reptile Anhanguera (name means old devil). Those pterosaurs with teeth in their beaks were probably fish-feeders, swooping low over the sea (the early Atlantic ocean) and catching fish in their toothed beaks.

An Illustration of Anhanguera (Toothed Pterosaur)

Picture credit: Everything Dinosaur

To view models of pterosaurs and flying reptiles: Pterosaur and Prehistoric Animal Models.