Fossil Claw Indicates Giant Arthropods of the Devonian

Spiders can be quite frightening, especially at this time of year when some particular types of spider, such as the Wolf Spider take up residence in your house to avoid the wintry weather. Suddenly, seeing one of these animals scuttling along the living room floor can be enough to make anyone jump, but scientists in Germany have come across a fossil to really put the wind up anyone with a slight fear of arthropods.

Giant Sea Scorpion

Markus Poschmann of the Mainz museum, in Germany has found a 390-million-year-old fossil claw from what could be the biggest arthropod known to date. The fossil was found in a quarry near the town of Prum in western Germany. The fossil is part of a claw of a sea scorpion species named Jaekelopterus rhenaniae, this species had been described and named from other German finds last century but this new find reveals that this particular sea scorpion was a giant of the Devonian seas, reaching lengths in excess of 2.5 metres,

Based on the size of the claw, which is 46 cm long scientists have calculated that this animal would have grown to at least 2.5 metres in length, making it a contender for the largest ever arthropod. Certainly, based on these measurements this new find puts J. rhenaniae up alongside the likes of Pterygotus, another huge sea scorpion (known as Eurypterids).

Jaekelopterus rhenaniae

Jaekelopterus rhenaniae was probably a top predator during this part of the Devonian period, feeding on other arthropods, including smaller sea scorpions and fish. Markus and co-author Simon Braddy, a palaeobiologist from Bristol University have just had their work published in Biology Letters, a scientific journal.

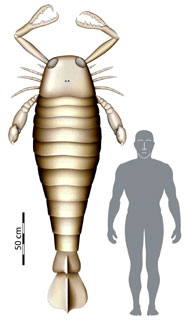

A Scale Drawing of Jaekelopterus (J. rhenaniae)

Jaekelopterus scale drawing. Life reconstruction of Jaekelopterus. Picture credit: Markus Poschmann.

Picture credit: Markus Poschmann

Lived in a Marine Environment

Based on other fossils of J. rhenaniae it can be seen that the limbs were relatively weak and would not have supported the weight of this huge animal without the assistance of water, so the scientists have speculated that this animal spent the vast majority of its life in a marine environment. It would have been a ferocious ambush predator, tackling any animal smaller than itself that ventured within reach. Once captured the powerful claws would have simply torn the victim to pieces, which could then have been passed up to the animal’s mouth on the underside of its heavily armoured head.

Despite this animal’s terrible appearance, it was no terror of the deep. Instead it would have patrolled the shallow coastal areas, where there would have been a greater congregation of potential prey. This theory is borne out by evidence from the matrix from which the fossil was taken. The rocks reveal that the claw was buried by sediments laid down in a coastal swamp or probably a river delta.

With arthropods this size swimming around its no wonder that the vertebrates decided to give living on land a go.

To view models and replicas of Palaeozoic invertebrates: CollectA Prehistoric Life Models.

It’s big…