Pictures of fossils, fossil hunting trips, fossil sites and photographs relating to fossil hunting and fossil finds.

Researchers Indentify the Last Meal of a Young Gorgosaurus

A newly published scientific paper has highlighted the diet of juvenile tyrannosaurs. Writing in the academic journal “Science Advances” the research team report that a young Gorgosaurus consumed the hind limbs from a pair of caenagnathid dinosaurs (Citipes elegans). This is the first time that stomach contents have been found in association with a tyrannosaur specimen.

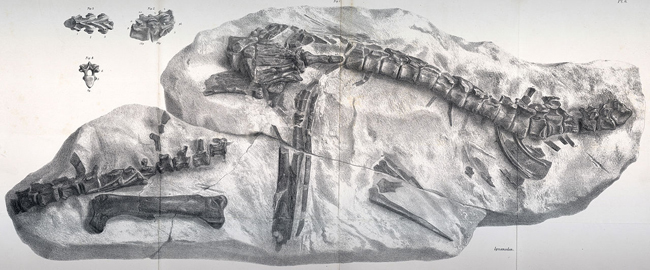

A superb, well-preserved Gorgosaurus libratus specimen was found by Royal Tyrrell Museum of Palaeontology staff in the Dinosaur Provincial Park in 2009. The specimen is a juvenile, thought to be between five and seven years of age. When it died this dinosaur weighed around 335 kilograms, only about 13% of the mass of an adult Gorgosaurus.

Stomach Contents Preserved in a Young Gorgosaurus

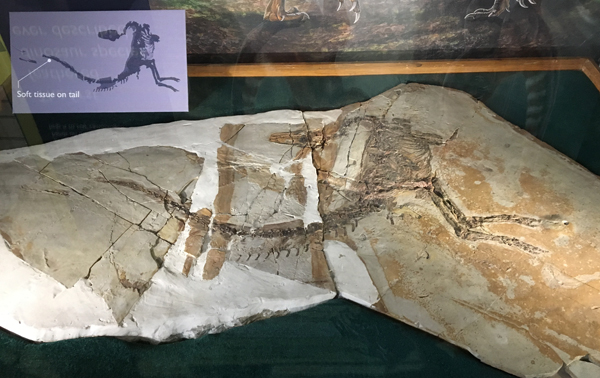

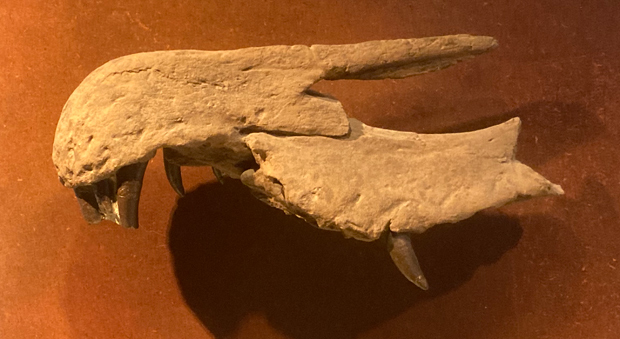

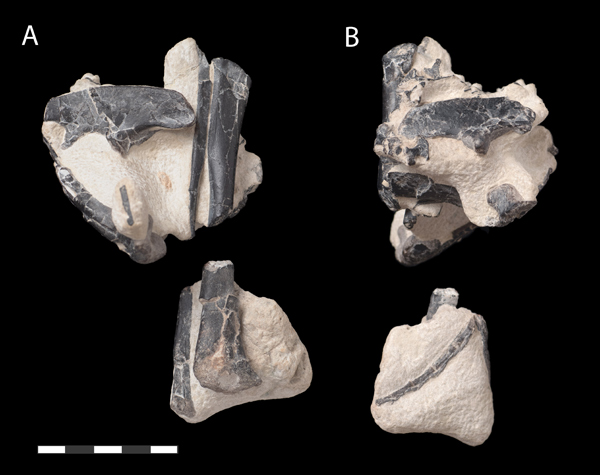

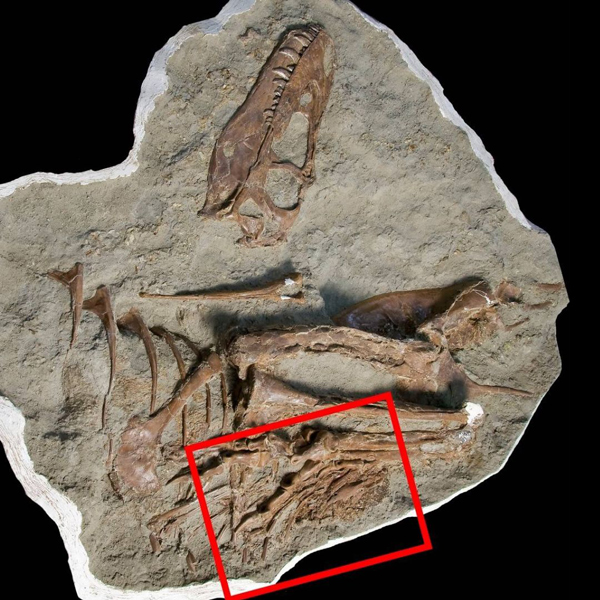

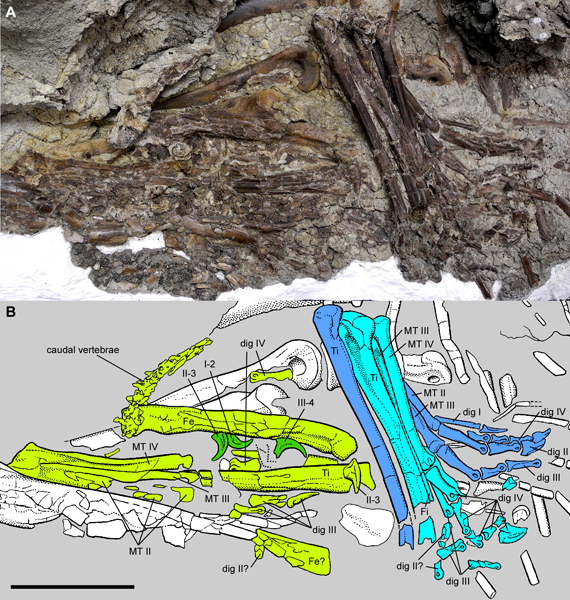

Whilst being cleaned and prepared at the Royal Tyrrell Museum of Palaeontology (Alberta, Canada), the partial remains of two small theropods were discovered inside the stomach cavity. The research team determined that this juvenile tyrannosaur ate the hind limbs of two caenagnathids. Rather than consuming the whole animal, the young tyrannosaur only ate the hind limbs (the meatiest parts of the body).

Analysis of the Citipes remains demonstrated that they were young animals, perhaps twelve months old. Alongside the Citipes limb bones caudal vertebrae were discovered. This suggests that there was preferential consumption of the Citipes hind quarters.

The elements highlighted in green in the illustration (above) are the remains of the first Citipes individual the gorgosaur consumed. The elements highlighted in blue are fossilised bones from the second Citipes individual eaten.

The Same Meal but Consumed at Different Times

As the elements of the two Citipes individuals are at different stages of digestion, the researchers were able to conclude that the gorgosaur’s stomach contents represent two different meals. These two juvenile Citipes could have been ingested hours or days apart. The presence of two dinosaurs of the same species and age in the stomach contents, ingested at different times, suggests that young caenagnathids may have been among the preferred prey of juvenile gorgosaurs.

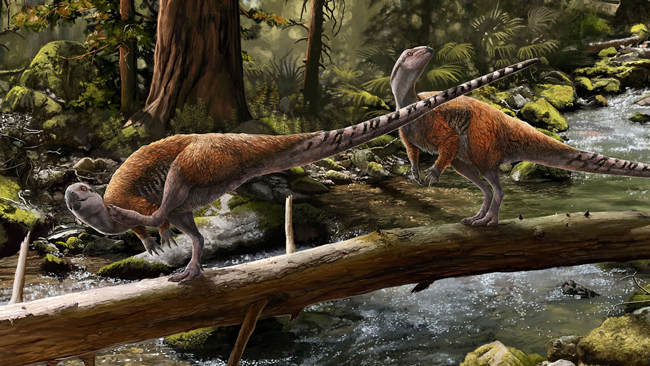

This specimen is the first to provide direct evidence that young gorgosaurs had different diets than their adult counterparts. When fully grown Gorgosaurus would have been an apex predator. Feeding traces preserved on fossil bones indicate that Gorgosaurus fed on ceratopsians and duck-billed dinosaurs.

This evidence suggests that tyrannosaurs occupied different ecological niches over their lifetime. As young tyrannosaurs grew and matured, they would have transitioned from hunting small and young dinosaurs to preying on large herbivores. This dietary shift likely began around the age of eleven, when their skulls and teeth started becoming more robust.

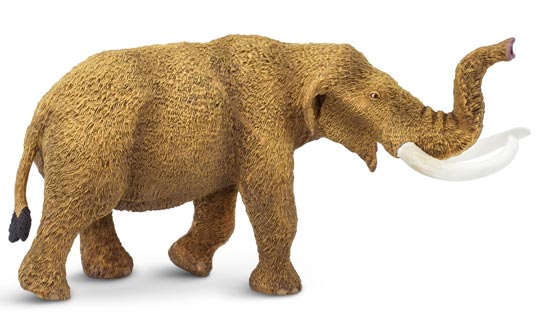

Picture credit: Everything Dinosaur

The picture (above) shows a replica of an adult Gorgosaurus. The skull is much more robust and powerful and the teeth proportionately larger. The model is from the PNSO Age of Dinosaurs range.

To view this range of prehistoric animal figures: PNSO Age of Dinosaurs Models and Figures.

A Way of Reducing Intraspecific Competition

Dietary differences are seen in animals at different ontogenic stages in modern ecosystems. These differences in diet provide a competitive advantage by lessening intraspecific competition for resources. Therefore, such a shift may have allowed juvenile and adult tyrannosaurs to coexist in the same environment with reduced conflict.

Being able to occupy different ecological niches during their lifespan was probably a key to the evolutionary success of the Tyrannosauridae.

Everything Dinosaur acknowledges the assistance of a media release from the Royal Tyrrell Museum of Palaeontology in the compilation of this article.

The scientific paper: “Exceptionally preserved stomach contents of a young tyrannosaurid reveal an ontogenetic dietary shift in an iconic extinct predator” by Francois Therrien, Darla K. Zelenitsky, Jared T. Voris, Gregory M. Erickson, Philip J. Currie, Christopher L. Debuhr and Yoshitsugu Kobayashi published in Science Advances.

Visit the award-winning Everything Dinosaur website: Everything Dinosaur.