Articles, features and information which have slightly more scientific content with an emphasis on palaeontology, such as updates on academic papers, published papers etc.

A New Herrerasaurian Dinosaur from the Upper Triassic of India

Scientists have named and described a new species of herrerasaurian dinosaur from India. The dinosaur which measured around three to four metres in length has been named Maleriraptor kuttyi. It fills a temporal gap between South American herrerasaurid dinosaurs and their younger relatives from North America. Herrerasaurs from South America are around nine million years older than herrerasaurs known from the Northern Hemisphere. The discovery of M. kuttyi shows that herrerasaurs survived in Gondwana at least during the early Norian after the extinction event that led to the demise of the rhynchosaurs.

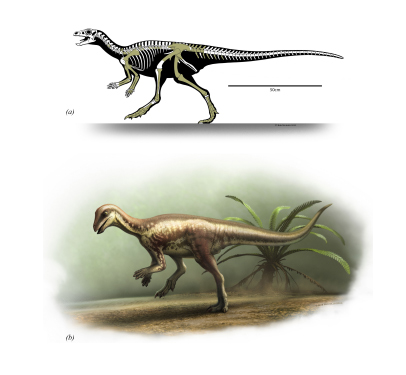

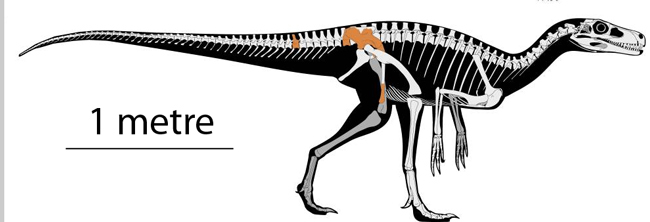

A skeletal drawing of the newly described herrerasaur from India Maleriraptor kuttyi. The shaded bones indicate known fossil material. Scale bar equals 1 metre. Picture credit: Royal Society Open Science (Maurício Silva Garcia).

Picture credit: Royal Society Open Science/Maurício Silva Garcia

Maleriraptor kuttyi

The fossilised remains of Maleriraptor kuttyi were collected more than four decades ago from the Upper Maleri Formation in Pranhita-Godavari Valley, less than half a mile south of the village of Annaram in south-central India. It is known from fragmentary material. The fossil remains consist of the first sacral vertebra, part of the second sacral rib, a vertebra representing a caudosacral element or the first in the caudal series, a single anterior (close to the base of the tail) caudal vertebra. In addition, the right ilium, both ends of the right pubis, and part of the left pubis have been identified.

The genus name is derived from the Upper Maleri Formation, in which the holotype and only known specimen was collected, and the Greek word raptor, meaning thief, which is an ending commonly used for theropod genera. The species name commemorates the late T. S. Kutty, who discovered the holotype and co-authored its preliminary description with some of the authors of the recently published study.

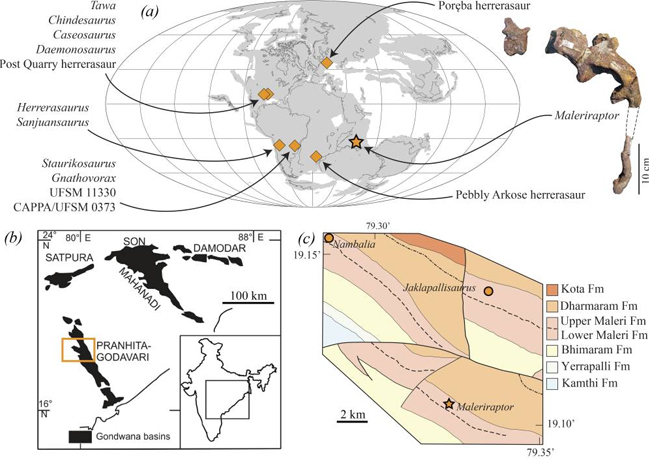

Geographic and stratigraphic occurrence of Maleriraptor kuttyi. Palaeomap of the Late Triassic depicting the occurrences of the herrerasaurs (a). Overview of the Gondwana basins in India (b), with the Pranhita-Godavari valley highlighted and (c) detailed geological map of a portion of the Pranhita-Godavari valley indicating the type localities of the nominal dinosaur species of the Upper Maleri Formation. Picture credit: Royal Society Open Science.

Picture credit: Royal Society Open Science

Herrerasaurids Surviving into the Norian

The deposition of the Upper Maleri Formation probably occurred shortly after the extinction of rhynchosaurs, which are abundantly recorded in the Lower Maleri Formation, but completely unknown from the geologically younger Upper Maleri Formation.

Mike from Everything Dinosaur commented:

“Maleriraptor kuttyi demonstrates that herrerasaurs survived in Gondwana after the extinction event that wiped out the once abundant and geographically widespread herbivorous rhynchosaurs.”

The researchers conclude that this newly described Indian herrerasaur fills a temporal gap between the Carnian South American herrerasaurids and the younger middle Norian-Rhaetian herrerasaurs of North America.

The scientific paper: “A new herrerasaurian dinosaur from the Upper Triassic Upper Maleri Formation of south-central India” by Martín D Ezcurra, Maurício Silva Garcia, Fernando E Novas, Rodrigo Temp Müller, Federico L Agnolín and Sankar Chatterjee published by the Royal Society Open Science.

Visit the Everything Dinosaur website: Prehistoric Animal Models.