Fossil finds, new dinosaur discoveries, news and views from the world of palaeontology and other Earth sciences.

New Study Shows Plant-eating Dinosaurs Ate Plants Differently

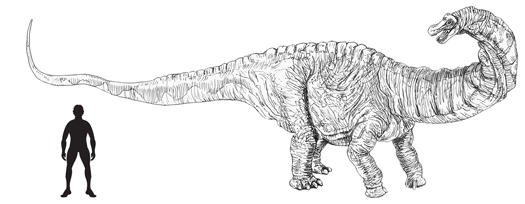

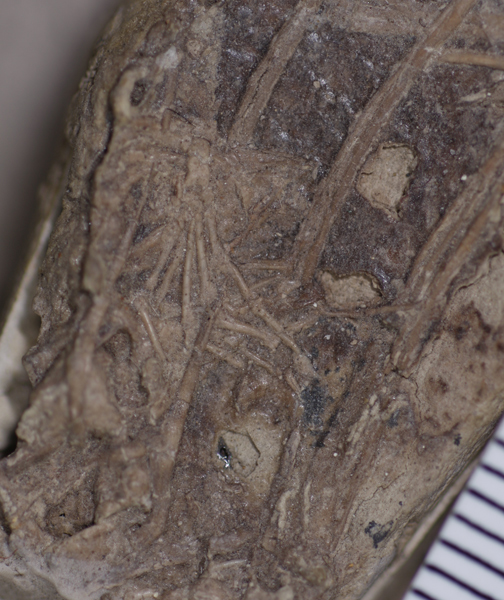

Newly published research demonstrates that plant-eating, ornithischian dinosaurs had different ways of tackling the plants that made up their diet. Scans of the skulls of five, herbivorous dinosaurs, all members of the bird-hipped group (Ornithischia), were used to create three-dimensional models of the skull, teeth and jaws. These computer models were then subjected to a series of stress tests measuring the jaw muscles and calculating bite forces to help palaeontologists understand how different feeding strategies evolved in the Dinosauria.

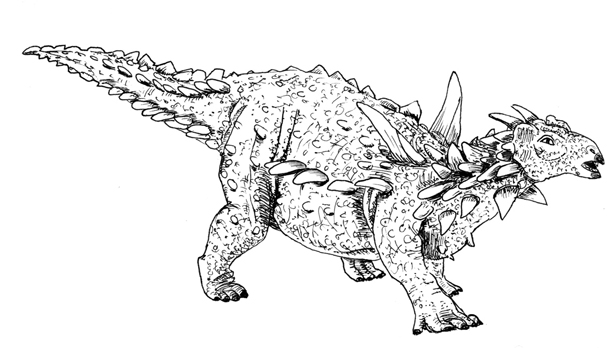

Picture credit: Everything Dinosaur

Plant-eating Dinosaurs

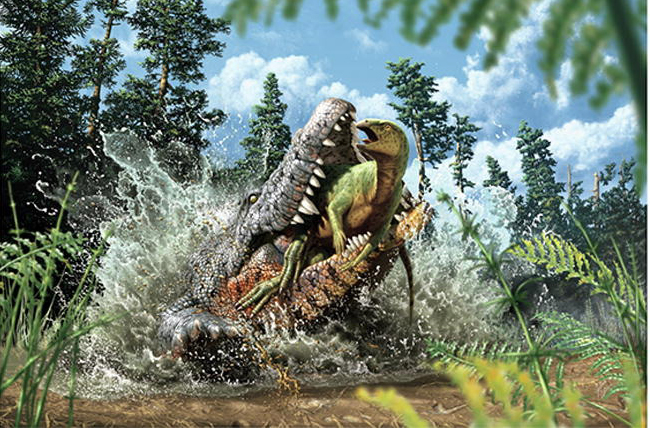

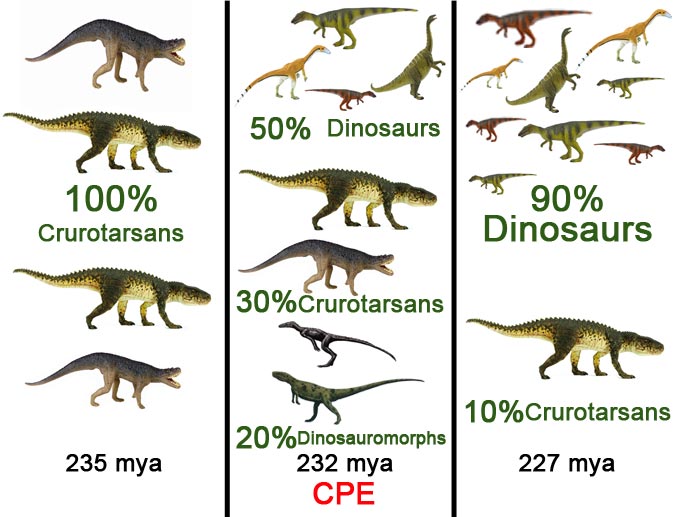

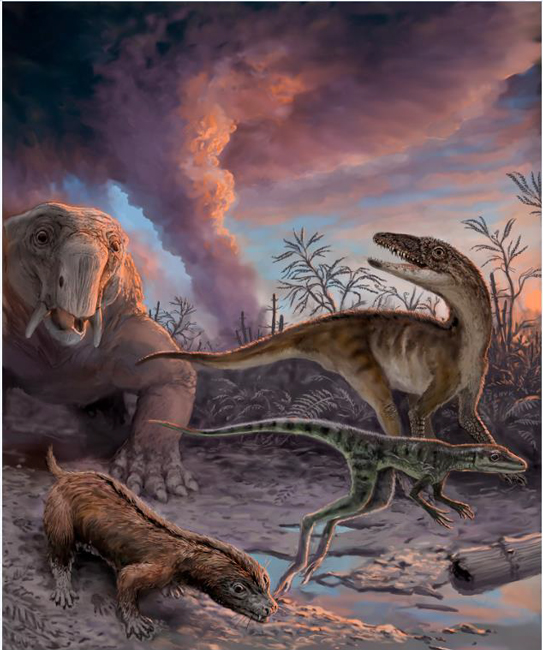

It is thought that the very earliest dinosaurs were carnivorous. However, quite early in their evolutionary history, the Dinosauria diversified and new forms with different diets (herbivory and omnivory) evolved.

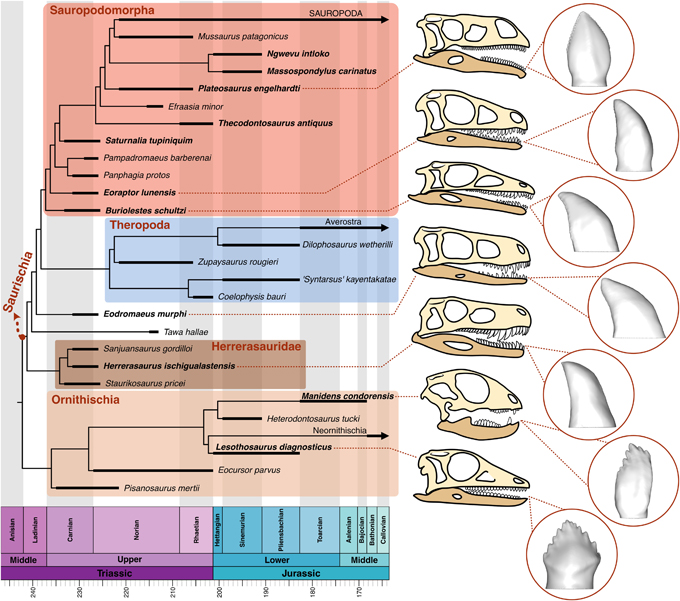

In a recently published study (December 2022), analysis of dinosaur tooth shape suggested that the ancestors of the huge, herbivorous sauropods were meat-eaters, whilst many groups of plant-eating, ornithischian dinosaurs were ancestrally omnivorous.

To read Everything Dinosaur’s blog post about this research: Tooth Shape Helps Shape Dinosaur Diet.

Earliest Representatives of Major Ornithischian Groups

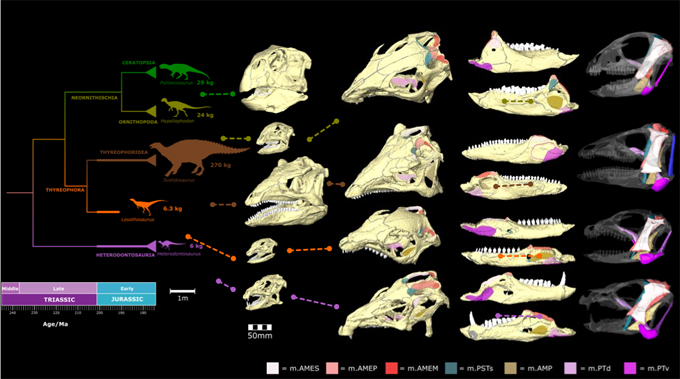

The skull and jaw muscles of some of the earliest representatives of major families within the Ornithischia were studied namely:

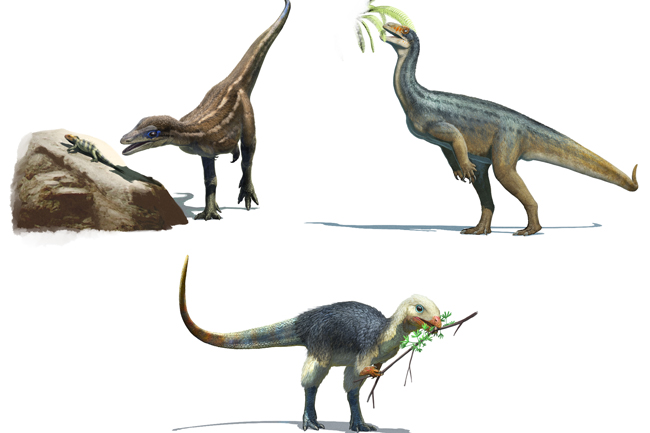

- Heterodontosaurus – Heterodontosauridae family from the Early Jurassic.

- Lesothosaurus – A basal ornithischian known from the Early Jurassic, possibly part of the early ornithopod lineage or perhaps an ancestor of armoured dinosaurs (Thyreophora).

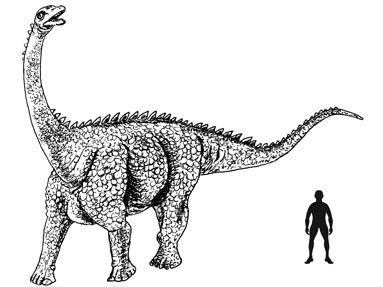

- Scelidosaurus – An early member of the Thyreophora (Early Jurassic).

- Hypsilophodon – Regarded as a basal ornithopod (Early Cretaceous).

- Psittacosaurus – A basal member of the Marginocephalia clade (Early Cretaceous) which includes horned dinosaurs (ceratopsids) and the bone-headed dinosaurs (pachycephalosaurs).

Writing in the academic journal “Current Biology”, the research team, which included scientists from the University of Birmingham, the London Natural History Museum and Bristol University, conclude that these herbivorous dinosaurs evolved very different ways of tackling their diet of vegetation.

Skull Morphology and Jaw Musculature Reveal Different Feeding Strategies

Using computer models and finite element analysis to assess the impact of stress on the skull and bite forces the team discovered that Heterodontosaurus had disproportionately large jaw muscles in relation to the size of its skull. It had a powerful bite. As it was able to generate a higher bite force this would have helped it to consume tough plants. Scelidosaurus had a similar bite force, but relatively smaller jaw muscles compared to the size of its skull. Hypsilophodon, in contrast, had proportionately smaller jaw muscles, it could bite more efficiently but with less force.

Co-author of the study, Dr Stephan Lautenschlager (University of Birmingham), commented:

“We discovered that each dinosaur tackled the problems posed by a plant-based diet by adopting very different eating techniques. Some compensated for low eating performance through their sheer size, whilst others developed bigger jaw muscles, increased jaw system efficiency, or combined these approaches. Although these animals looked very similar, their individual solutions to the same problems illustrates the unpredictable nature of evolution.”

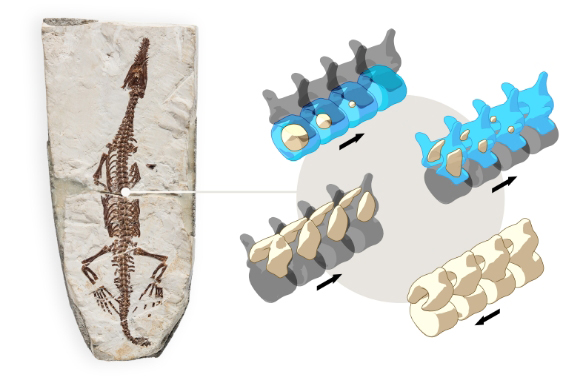

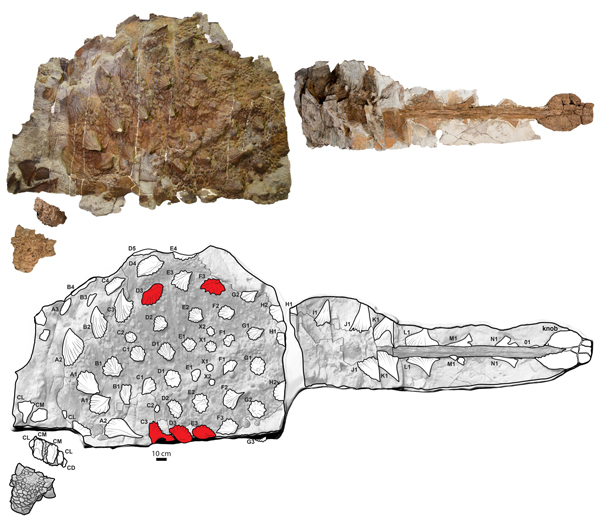

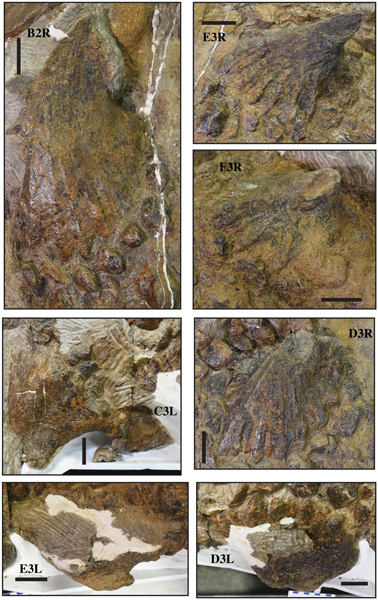

Compared to Birds and Crocodilians

The jaw muscles were reconstructed on the model skulls using extant archosaurs as templates (birds and crocodilians). Finite element analysis was then conducted to determine the potential bite force of each dinosaur. Finite element analysis involved dividing the skull into thousands of individual parts (called elements). The bite force these muscles can generate is calculated based on their size and arrangement.

Heat maps showed the different stress levels generated throughout each skull as the biting motion was simulated. The results revealed that although all of these dinosaurs were eating plants, each type of dinosaur had a different way of doing it.

Professor Paul Barrett (London Natural History Museum), explained that it was essential for palaeontologists to understand how dinosaurs evolved to feed on plants in so many ways. This diversity in feeding strategies helps to explain how these animals came to be the dominant primary consumers in terrestrial food chains for millions of years.

Lead author of the study, Dr David Button (University of Bristol) explained:

“When we compared the functional performance of the skull and teeth of these plant-eating dinosaurs, we found significant differences in the relative sizes of the jaw muscles, bite forces and jaw strength between them. This showed that these dinosaurs, although looking somewhat similar, had evolved very different ways to tackle a diet of plants.”

Dr Button went onto add:

“This research helps us understand how animals evolve to occupy new ecological niches. It shows that even similar animals adopting similar diets won’t always evolve the same characteristics. This highlights how innovative and unpredictable evolution can be.”

These differences in feeding strategy identified in this research demonstrates that each of these types of ornithischian dinosaur evolved a distinct solution to feeding on plants.

Everything Dinosaur acknowledges the assistance of a media release from the University of Birmingham in the compilation of this article.

The scientific paper: “Multiple pathways to herbivory underpinned deep divergences in ornithischian evolution” by David J. Button, Laura B. Porro, Stephan Lautenschlager, Marc E. H. Jones and Paul M. Barrett published in Current Biology.