Solnhofen Juvenile Pterosaur Bias Mystery Solved in New Study

Two remarkable juvenile Pterodactylus fossils have helped researchers to solve a puzzle concerning the Upper Jurassic deposits at Solnhofen. The Upper Jurassic Solnhofen archipelago of Germany has yielded a pterosaur assemblage that has long underpinned and continues to dominate much of our understanding of these Mesozoic flying reptiles. Pterosaur fossils from this location broadly fit into two categories. Firstly, there are the highly fragmentary fossils of adult, or sub-adults. Often a specimen is represented by a single bone. Secondly, there are the numerous very young pterosaurs* that are preserved almost intact and articulated.

A detailed analysis of two remarkable hatchling Pterodactylus fossils has helped scientists to put forward a plausible theory as to why these two types of fossil preservation, driven by ontogeny occurred. They postulate that these two baby pterosaurs perished in a violent storm. Young pterosaurs were caught in powerful tropical storms. Ironically, these powerful storms also created the ideal conditions to preserve their remains and hundreds more.

Picture credit: Rudolf Hima

The Mystery of the Hatchling and Juvenile Pterodactylus Specimens

The researchers, including scientists from the University of Leicester discovered broken humeri in the fossilised remains of two hatchling pterosaurs. These very young flying reptiles suffered broken wings. The cause of death for these pterosaurs nicknamed “Lucky I” and “Lucky II” by the researchers, has been revealed. Consider this a post-mortem on events that took place in the Late Jurassic around 150 million years ago.

Writing in the academic journal “Current Biology”, the team highlight that the preservation bias for large, more robust specimens was turned on its head in the waters of the Solnhofen lagoon. Small delicate animals such as a juvenile Pterodactylus would rarely make it into the fossil record. However, occasionally nature conspires to produce the conditions that permit the preservation of diminutive pterosaurs.

Lead author of the paper, Rab Smyth (University of Leicester) explained:

“Pterosaurs had incredibly lightweight skeletons. Hollow, thin-walled bones are ideal for flight but terrible for fossilisation. The odds of preserving one are already slim and finding a fossil that tells you how the animal died is even rarer.”

Examining the Tiny Fossils Under UV Light

Examination of the tiny fossils under UV light revealed the presence of broken upper arm bones (humeri) in the two specimens. These details, easily overlooked, provided the evidence that their wings were subjected to a strong twisting force. This was probably caused by a strong gust of wind rather than a collision against a hard surface.

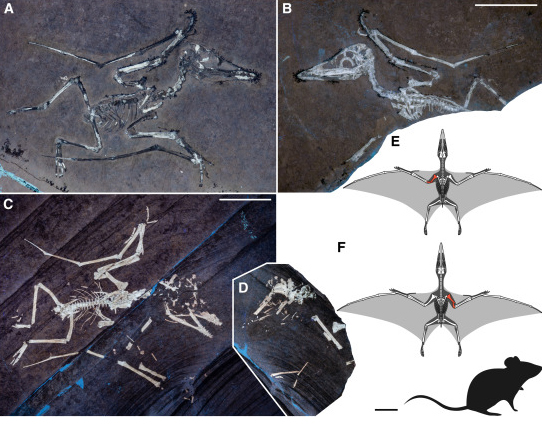

Broken bones offer clues to the perils of pterosaur flight. Skeletal reconstructions of the two Pterodactylus hatchlings are shown in flight position, with broken bones marked in red. UV images reveal clear breaks in the upper arm bones. A silhouette of a house mouse (Mus musculus) is included for scale. Picture credit: Smyth et al (University of Leicester).

Picture credit: Smyth et al (University of Leicester)

The picture (above) shows fossil specimen MBH 250624-07 (Lucky I) as (A) part and (B) counterpart. They are photographed under UV light. The broken left humerus is in a predominantly ventral view, with the skull exposed in lateral view. Images C and D show the part and counterpart of Lucky II (SNSB-BSPG 1993 XVIII 1508 a/b), photographed in ventral view. The fossil has a fractured right humerus.

Skeletal reconstructions of Lucky I (E) and Lucky II (F) along with a silhouette of a house mouse (Mus musculus) to provide scale.

Highlighting how Local Environmental Conditions can Distort the Fossil Record

The skeletons are virtually complete and articulated. Except for one small detail. Both specimens show the same unusual injury – a clean, slanted fracture to the humerus. Lucky’s left wing and Lucky II’s right wing were both broken in a way that suggests a powerful twisting force. The researchers postulate that these unfortunate flying reptiles were caught up in a storm.

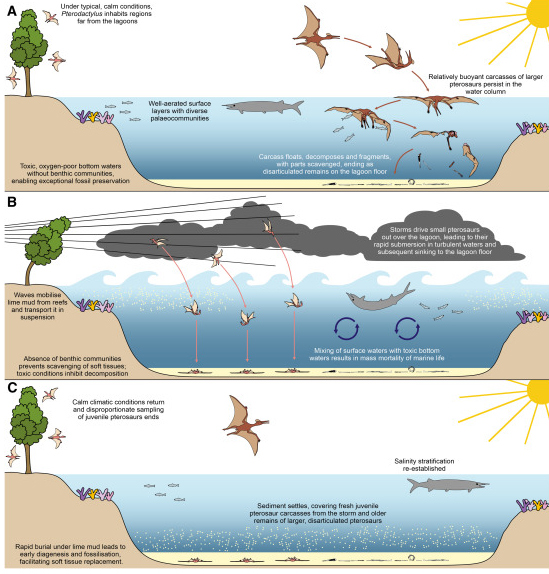

Pterosaur fossil preservation in the Solnhofen deposits. (A) Most of the time, pterosaurs stood little chance of becoming fossils. Decaying larger individuals sometimes left behind scattered bones that reached the lagoon floor, but smaller pterosaurs were usually lost without trace. (B) Storms, however, created very different conditions. Powerful winds and waves dragged the bodies of small and young pterosaurs into deeper waters. At the same time, these storms stirred up salty water from the lagoon floor. This water contained almost no oxygen, and when it mixed with the surface waters, it triggered sudden die-offs of marine life. These toxic waters acted as a barrier to scavengers and decay, allowing pterosaur bodies to sink largely untouched. The final step came when lime-rich mud, carried by the storm, rapidly buried the remains. This quick covering not only protected soft tissues from decay but also preserved fragments of larger pterosaurs that had been deposited earlier. Together, these rare conditions explain why fossils from Solnhofen are so well preserved. Picture credit: Smyth et al (University of Leicester).

Picture credit: Smyth et al (University of Leicester)

Catastrophically injured, the pterosaurs plunged into the surface of the lagoon, drowning in the storm driven waves and quickly sinking to the seabed where they were rapidly buried by very fine limy muds stirred up by the violent storm events. This rapid burial allowed for the remarkable preservation seen in their fossils. The researchers have highlighted how local environmental conditions can lead to distortions in the fossil record.

Ironic Names for Juvenile Pterodactylus Fossils

Lucky I and Lucky II are ironic nicknames for these pterosaur fossils. These animals may only have been a few days or weeks old when they perished. There are many other small pterosaurs preserved in the Solnhofen limestone deposits. These too, might present very young flying reptiles. They may not demonstrate obvious signs of skeletal trauma but they could have met a similar fate as Lucky I and Lucky II. Unable to resist the strength of storms these young pterosaurs were also flung into the lagoon. This discovery may explain why smaller fossils are so well preserved – they were a direct result of storms – a common cause of death for pterosaurs that lived in the region.

Larger, stronger individuals, it seems, were able to weather the storms and rarely followed the Luckies stormy road to death. They did eventually die though but likely floated for days or weeks on the now calm surfaces of the Solnhofen lagoon, occasionally dropping parts of their carcasses into the abyss as their bodies slowly decomposed.

Rab Smyth added:

“For centuries, scientists believed that the Solnhofen lagoon ecosystems were dominated by small pterosaurs. But we now know this view is deeply biased. Many of these pterosaurs weren’t native to the lagoon at all. Most are inexperienced juveniles that were likely living on nearby islands that were unfortunately caught up in powerful storms.”

The researchers conclude that catastrophic storm sampling explains the high numbers of small, potentially juvenile pterosaurs preserved in the Solnhofen deposits. This study also has implications for the perceived flight abilities of very young flying reptiles. Wing injuries in neonatal pterosaurs were likely caused by violent storm events and this research supports precocial flight ability.

A “Lucky” Break

Co-author of the paper, Dr David Unwin (University of Leicester) commented:

“When Rab spotted Lucky we were very excited but realised that it was a one-off. Was it representative in any way? A year later, when Rab noticed Lucky II we knew that it was no longer a freak find but evidence of how these animals were dying. Later still, when we had a chance to light-up Lucky II with our UV torches, it literally leapt out of the rock at us – and our hearts stopped. Neither of us will ever forget that moment.”

*very young pterosaurs – there is some debate over whether the fossils all represent hatchlings or very young animals. In addition, describing these two specimens as representatives of the taxon Pterodactylus has drawn criticism. It has been suggested that this study could have included a detailed phylogenetic analysis rather than assign the two fossil specimens to what has been referred to as a “taxonomic wastebasket”.

Everything Dinosaur acknowledges the assistance of a media release from the University of Leicester in the compilation of this article.

The scientific paper: “Fatal accidents in neonatal pterosaurs and selective sampling in the Solnhofen fossil assemblage” by Robert S.H. Smyth, Rachel Belben, Richard Thomas and David M. Unwin published in Current Biology.

The award-winning Everything Dinosaur website: Everything Dinosaur.