A fossil specimen found in a cupboard at the Natural History Museum (London) proves that there were modern lizards in the Triassic. The Squamata (lizards and snakes), were thought to have had their evolutionary origins in the Middle Jurassic, but analysis of this previously undescribed specimen pushes back the origins of this Order by tens of millions of years.

A Gloucestershire Quarry

The fossil was collected along with other reptile specimens from a quarry near to Tortworth in Gloucestershire, it was labelled “Clevosaurus and one other reptile”. Clevosaurus material, whilst not common, is well-known from Triassic-aged rocks from the south-west of England, particularly in Avon and Gloucestershire. Clevosaurs are members of an ancient Order of reptiles called the Rhynchocephalia, of which there is only one extant genus today, the Tuatara. Although they may resemble lizards, they are distinct and not members of the Squamata.

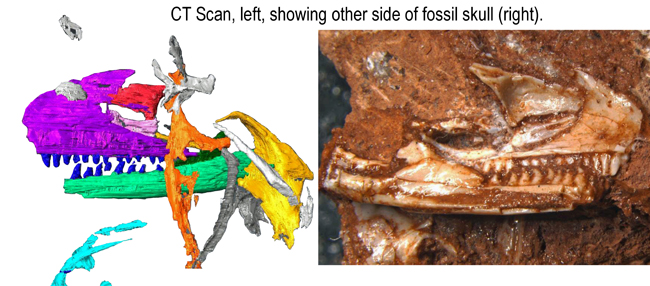

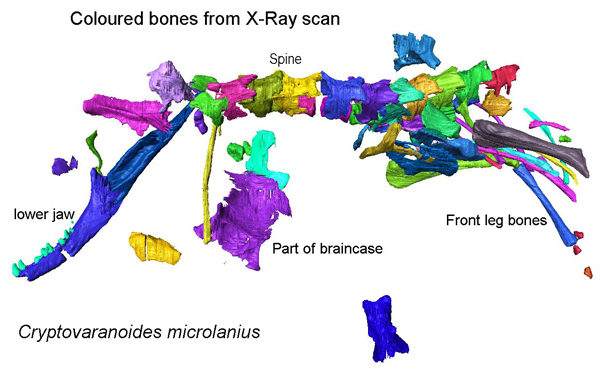

X-ray Scans and Computer Models

At the time the fossil was collected, the technology did not exist to permit scientists to investigate the specimen in detail. Writing in the academic journal “Science Advances” the researchers conclude that based on the detailed X-ray scans (computerised tomography) of the fossil and the computer-generated models that resulted, the fossil represents a basal member of the reptilian lineage that would lead to modern snakes and lizards.

This fossil indicates that the origin of lizards and snakes (Squamata) was much further back in geological time than previously thought.

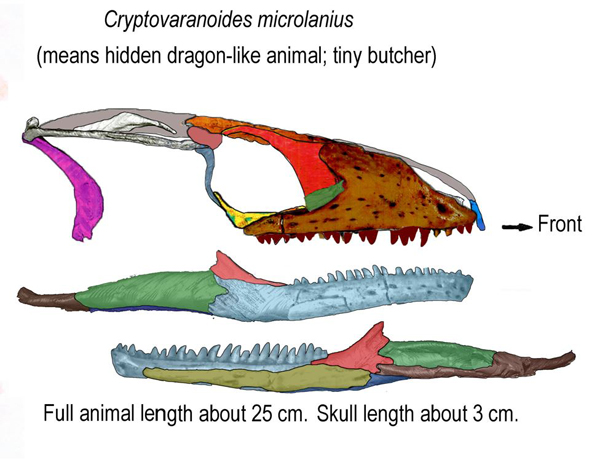

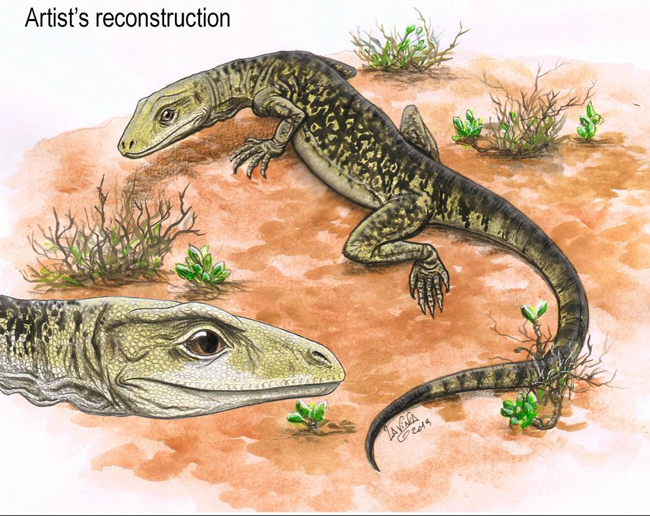

The research team, led by Dr David Whiteside of Bristol University’s School of Earth Sciences, have named their incredible discovery Cryptovaranoides microlanius which means “small butcher” in tribute to its jaws that were filled with sharp-edged slicing teeth.

Explaining the significance of this research Dr Whiteside stated:

“I first spotted the specimen in a cupboard full of Clevosaurus fossils in the storerooms of the Natural History Museum in London where I am a Scientific Associate. This was a common enough fossil reptile, a close relative of the New Zealand Tuatara that is the only survivor of the group, the Rhynchocephalia, that split from the squamates over 240 million years ago. As we continued to investigate the specimen, we became more and more convinced that it was actually more closely related to modern day lizards than the Tuatara group.”

Modern Lizards

Cryptovaranoides is clearly a squamate as its anatomy differs from the Rhynchocephalia. The braincase is different, it had different neck vertebrae and the anatomy of the shoulder girdle is more reminiscent of a modern lizard than a Tuatara. The scientists identified only one major primitive feature not found in modern squamates, an opening on one side of the end of the upper arm bone, the humerus, where an artery and nerve pass through.

Other Primitive Characteristics

Analysis of the Cryptovaranoides material revealed that this crown squamate does have some other, apparently primitive characters such as a few rows of teeth on the bones of the roof of the mouth, but experts have observed the same in the living European Glass lizard and many snakes such as Boas and Pythons have multiple rows of large teeth in the same area. Despite this, it is advanced like most living lizards in its braincase and the bone connections in the skull suggest that it was flexible.

Co-author of the paper Professor Mike Benton (University of Bristol) added:

“In terms of significance, our fossil shifts the origin and diversification of squamates back from the Middle Jurassic to the Late Triassic. This was a time of major restructuring of ecosystems on land, with origins of new plant groups, especially modern-type conifers, as well as new kinds of insects, and some of the first of modern groups such as turtles, crocodilians, dinosaurs, and mammals.”

Dr Whiteside paid tribute to the late Pamela L. Robinson who recovered the fossil from the quarry and did a lot of preparation work on the specimen, however, with no access to CT scanning technology, she was not able to perceive the significance of her discovery.

Everything Dinosaur acknowledges the assistance of a media release from the University of Bristol in the compilation of this article.

The scientific paper: “A Triassic crown squamate” by Whiteside, D. I., Chambi-Trowell, S. A. V., and Benton, M J. published in Science Advances.

Leave A Comment