Dinosaur Mummies an Alternate Fossilisation Pathway According to New Research

Research into a beautifully preserved Edmontosaurus fossil suggests that dinosaur mummies might be more common than previously thought. The Edmontosaurus specimen found by Tyler Lyson when exploring Slope County (North Dakota) and Hell Creek Formation exposures contained therein is providing palaeontologists with an insight into the fossilisation process that might produce a “dinosaur mummy”.

A mummified dinosaur was thought to require two mutually exclusive taphonomic processes in order to form. Firstly, to have the carcase exposed on the surface for a considerable portion of time to permit the remains to dry out and become desiccated. Secondly, rapid burial and deposition to preserve what remains of the corpse.

The taphonomy of the Edmontosaurus specimen (NDGS 2000), suggests that there may be other circumstances the lead to the mummified remains of dinosaurs.

Dinosaur Mummies – Hooves and Fingers (E. annectens)

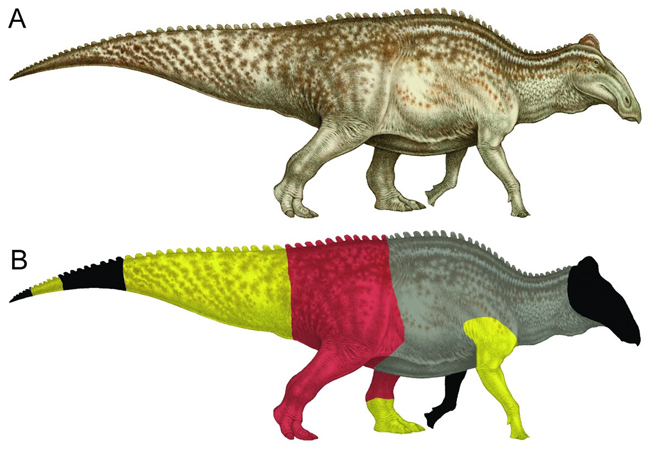

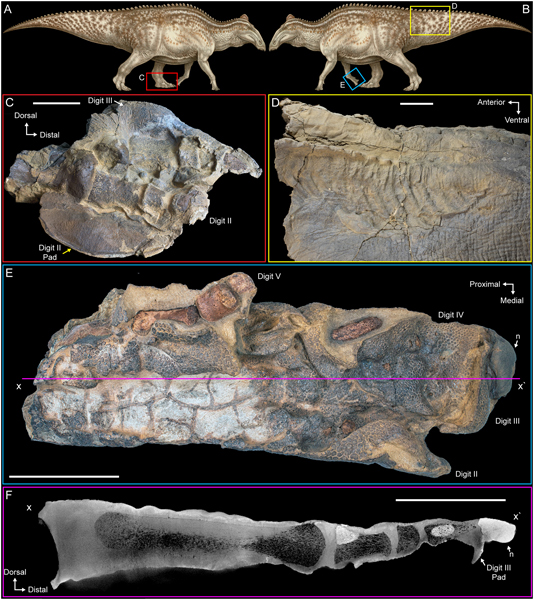

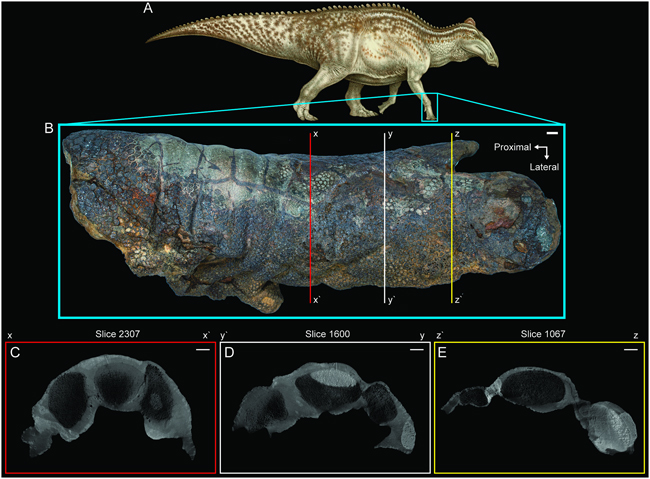

A team of scientists, including researchers from University of Tennessee–Knoxville, Knoxville, Tennessee and the North Dakota Geological Survey team, writing in the academic journal PLoS One propose a new explanation for how such fossil specimens might form. Large areas of desiccated and seemingly deflated skin have been preserved on the limbs and tail. Such is the degree of preservation of the front limb, (manus) that palaeontologists have discovered that Edmontosaurus (E. annectens) had a hoof-like nail on the third digit.

This discovery led to a substantial revision of Edmontosaurus limb anatomy in prehistoric animal replicas, as epitomised by the recently introduced CollectA Deluxe 1:40 scale Edmontosaurus.

To read a blog article that contains a video review of the Edmontosaurus and explains more about the “dinosaur mummy” research: Everything Dinosaur Reviews the CollectA Deluxe Edmontosaurus Dinosaur Model.

Evidence of Scavenging

The research team identified bite marks from carnivores upon the dinosaur’s skin. These are the first examples of unhealed carnivore damage on fossil dinosaur skin, and furthermore, this is evidence that the dinosaur carcass was not protected from scavengers by being rapidly buried, yet it became a mummy nonetheless.

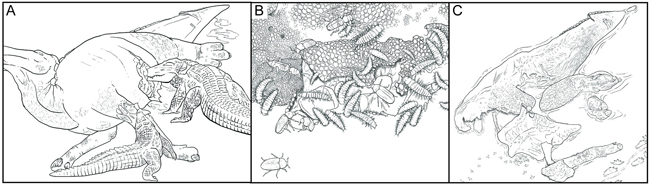

Many of the marks suggest bites from the conical teeth of crocodyliforms, although pathology associated with the tail is more difficult to interpret. The researchers suggest that some of the “V-shaped” patterns identified suggest that flexible, clawed digits rather than more rigidly fixed teeth, may have been responsible for these injuries. Perhaps these marks were caused by feeding deinonychosaurs (Dakotaraptor steini) or perhaps a juvenile T. rex.

Examining the Decomposition of Carcases

If the carcase was scavenged, then it was not buried rapidly and one of the supposed pre-requisites for “dinosaur mummification” did not occur with this fossil specimen. Instead, the researchers propose an alternative route for the creation of such remarkable fossils, a theory that has been influenced by what is observed in the world today. When scavengers feed on a carcase, they rip open the body and feed on the internal organs. Punctures made in the body allow fluids and gases formed by decomposition to escape, thus permitting the skin to dry out, forming a desiccated, dried out husk.

Dinosaur Skin More Commonly Preserved

The research team postulate that if the more durable soft tissues can persist some months prior to burial to permit desiccation to occur, then dinosaur skin fossils, although rare, are possibly, more commonly preserved than expected.

A New Theory on How “Dinosaur Mummies” Could Form

It is important to make clear that what a palaeontologist refers to as a “dinosaur mummy” is not the same as the mummified remains of an Egyptian deity. The skin and other soft tissues are permineralised, they are rock, although it is noted that molecular sampling of this Edmontosaurus specimen yielded putative dinosaurian biomarkers such as evidence of degraded proteins, suggesting that soft tissue was preserved directly in this specimen.

Generally, the two presumed prerequisites for mummification, that of being exposed on the surface for some time to permit the corpse to desiccate and rapid burial are incompatible. So, the researchers propose a new theory on how a “dinosaur mummy” could form:

- A corpse is scavenged creating puncture marks to allow fluids and gases to escape.

- Smaller organisms such as invertebrates and microbes exploit these punctures to access the internal organs and other parts of the skeleton.

- Consumption from within in conjunction with decomposition allows the skin to deflate and to drape over the underlying bones that are more resistant to feeding and decay.

The scientists hope that this new paper will help with the excavation, collection and preparation of fossils. The presence of soft tissues and biomarkers such as degraded proteins demonstrate that rapid burial may not be a pre-requisite to permit their preservation. As a result, such evidence as skin, soft tissue and biomarkers may be more common in the fossil record than previously thought.

The scientific paper: “Biostratinomic alterations of an Edmontosaurus “mummy” reveal a pathway for soft tissue preservation without invoking ‘exceptional conditions'” by Stephanie K. Drumheller, Clint A. Boyd, Becky M. S. Barnes and Mindy L. Householder published in PLoS One.