Sometimes serendipity and palaeontology combine, for example, a sharp-eyed field team member spotting a hadrosaur fossil specimen eroding out of a small hill in the Dinosaur Provincial Park (Alberta, Canada). The fossils could represent a rare skeleton of a juvenile and there is evidence that skin impressions have been preserved.

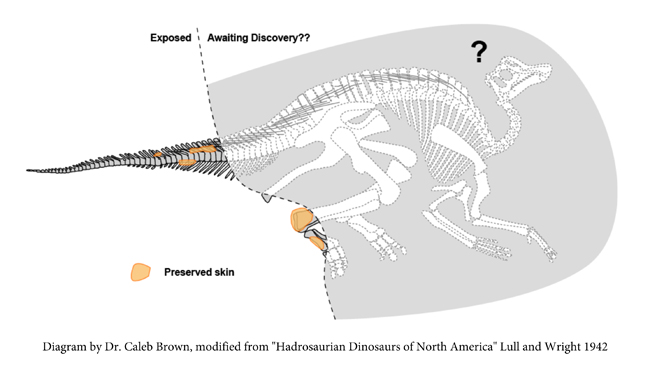

Whilst hadrosaur fossils are relatively common in this part of southern Alberta, the animal’s tail and right hind foot are orientated in the hillside to suggest that the entire skeleton may still be preserved within the rapidly eroding mudstone.

Potentially a Very Significant Fossil Discovery

Whole dinosaur skeletons are extremely rare, this specimen tentatively referred to as a “dinosaur mummy” could provide important new information on juvenile hadrosaurs and the ontogeny of duck-billed dinosaurs.

Spotting a Hadrosaur

The exposed caudal vertebrae (tail bones) show preserved skin impressions as does the exposed right ankle. The size of the bones and the distance between the tail and the astragalus (ankle) suggest that these are the fossilised remains of a young hadrosaur.

Discovering a Duck-billed Dinosaur

During a field school scouting visit in 2021 to look for possible excavation sites, Dr Brian Pickles (University of Reading) was leading a small team examining one location when volunteer crew member Teri Kaskie spotted the fossil skeleton protruding from the hillside.

The first international palaeontology field school is taking place, involving academics and students from the University of Reading and the University of New England in Australia. In collaboration with researchers from the Royal Tyrrell Museum (Drumheller, Alberta), the team are working together to excavate the skeleton and ensure the material that remains in the hill is protected from the elements.

The first part of the conservation work involves coating the fossil site in a thick layer of mud, to help conserve the delicate fossils and to prevent erosion.

An Exciting Fossil Discovery

Commenting on the significance of this hadrosaur fossil find, Dr Pickles stated:

“This is a very exciting discovery, and we hope to complete the excavation over the next two field seasons. Based on the small size of the tail and foot, this is likely to be a juvenile. Although adult duck-billed dinosaurs are well represented in the fossil record, younger animals are far less common. This means the find could help palaeontologists to understand how hadrosaurs grew and developed.”

Vertebrate palaeontologist from the Royal Tyrrell Museum, Dr Caleb Brown added:

“Hadrosaur fossils are relatively common in this part of the world but another thing that makes this find unique is the fact that large areas of the exposed skeleton are covered in fossilised skin. This suggests that there may be even more preserved skin within the rock, which can give us further insight into what the hadrosaur looked like.”

A Substantial Project

Collecting the entire skeleton is going to take many months and the site will have to be closed down and secured as the weather worsens towards winter. It may take several field seasons to complete this work. Once the specimen has been removed from the field, it will be delivered to the Royal Tyrrell Museum’s Preparation Laboratory, where skilled technicians will work to uncover and conserve the fossilised bones.

At this time, the scientists are unsure as to how complete the specimen is and which genus the fossils represent. Species identification will only be possible if a substantial proportion of the skeleton, including skull material can be recovered.

Which Hadrosaur?

Several different types of hadrosaur are known from the Dinosaur Provincial Park Formation (Campanian faunal stage). Lambeosaurines are represented by Corythosaurus, Parasaurolophus and Lambeosaurus whilst members of the Saurolophinae subfamily represented include Gryposaurus and Prosaurolophus. As more of the skeleton is prepared, the researchers are hopeful that they will be able to confirm the species.

Everything Dinosaur acknowledges the assistance of a media release from Reading University in the compilation of this article.

Leave A Comment