The recently aired television documentary series “Prehistoric Planet” depicted giant azhdarchid pterosaurs such as Quetzalcoatlus and Hatzegopteryx as competent aeronauts extremely proficient at flight and capable of travelling huge distances without ever having the need to land. This idea has been challenged in newly published research that suggests Quetzalcoatlus was more suited to short-range flights.

The Schleich Quetzalcoatulus figure in resting pose. Quetzalcoatlus takes to the air. A new study suggests that Quetzalcoatlus and other super-sized azhdarchid pterosaurs were probably short-range fliers. Picture credit: Everything Dinosaur.

Picture credit: Everything Dinosaur

The picture (above) shows a Schleich Quetzalcoatlus figure.

To view the Schleich range of models in stock at Everything Dinosaur: Schleich Prehistoric Animal Figures.

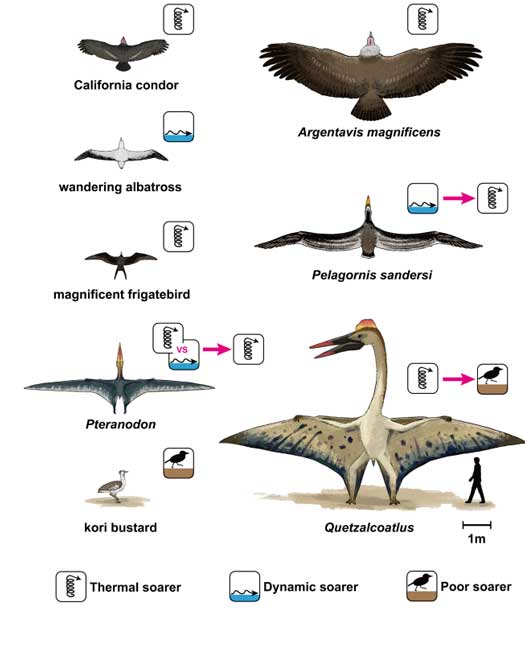

The Largest Known Flying Animals

A number of vertebrates are volant (capable of powered flight). Amongst this diverse and eclectic group consisting of bats, birds and pterosaurs are some giants. For example, Pelagornis sandersi*, a pelagornithid bird from the Late Oligocene of Southern Carolina had an estimated wingspan of about 7 metres. Argentavis magnificens was an enormous condor from the Late Miocene of Argentina. It had a wingspan in excess of 6 metres and it was very much larger than its extant, distant relative the California condor (Gymnogyps californianus).

During the Late Cretaceous enormous pterosaurs dominated the skies. Pteranodon was thought to be one of the biggest, but over the last fifty years or so, evidence has emerged of the Azhdarchidae – a family of Late Cretaceous flying reptiles, some members of which such as Hatzegopteryx, Quetzalcoatlus, Arambourgiania and the recently described Thanatosdrakon* were the largest flying animals known to science.

Comparing Today’s Large Birds with Ancient Flyers

A new study, led by Dr Yusuke Goto from Nagoya University (Japan), along with researchers from the Centre d’Etudes Biologiques de Chizé (France) and the University of Tokyo (Japan), calculated and compared the ability of some of these ancient flyers to the capabilities of large, extant birds such as the Wandering albatross (Diomedea exulans), the California condor, the Magnificent frigatebird (Fregata magnificens) and the Kori bustard (Ardeotis kori). The Kori bustard has a bodyweight in the region of 10-18 kilograms, it is the heaviest flying bird alive today.

The team set out to quantify the soaring performance of these animals using a combination of potential speed of flight, soaring efficiency and the wind speed and conditions required to sustain aerial activity.

They analysed two types of soaring behaviour:

- Thermal soaring – which uses updrafts arising from the land or ocean to ascend and glide. A method of flight observed in eagles and frigatebirds.

- Dynamic soaring – which uses wind gradients over the ocean, as demonstrated by albatrosses and petrels.

Scientists set out to examine the soaring abilities of extinct giant birds and giant pterosaurs including the taxa Pteranodon and Quetzalcoatlus. The giant Argentavis magnificens was a thermal soarer like the extant California condor, whilst Pelagornis sandersi, thought to have used wind currents over bodies of water to stay aloft was found to be better suited to thermal soaring. Analysis of the wings of Pteranodon suggest thermal soaring capacities whilst in this study the giant azhdarchid Quetzalcoatlus was thought to be more adapted to a terrestrial existence and flew short distances with a similar flight habit to the Kori Bustard, the heaviest, living volant bird.The icons indicate dynamic soarer, thermal soarer, and poor soarer, and summarize the main results of this study. The pink arrows indicate the transition from a previous expectation or hypothesis to the knowledge updated in the study. Image credit: Goto et al.

Image credit: Goto et al

The Soaring Abilities of Pteranodon

The scientists concluded that Pteranodon, fossils of which are associated with marine environments, was probably an ocean dweller, excelling at soaring flight using updrafts over the sea. The predicted flying style of Pteranodon was similar to that seen in extant, ocean-going frigatebirds.

Picture credit: Zdeněk Burian

Challenging Perceptions About Quetzalcoatlus

This analysis challenges perceptions about the flight capabilities of Quetzalcoatlus. The team concluded that this azhdarchid was not well adapted for soaring flight, even when wind speeds and atmospheric conditions were favourable.

Previous studies had proposed that Quetzalcoatlus was capable of travelling hundreds if not thousands of miles without having the need to land, this study showed that its thermal soaring abilities were much lower than that seen in living birds.

The idea that large azhdarchids were terrestrial hunters has been proposed previously, but the research team go further suggesting that Quetzalcoatlus and other giants were short-range flyers and did spend most of their time on land. The Kori bustard is proposed as a modern-day analogue for the biggest members of the Azhdarchidae. It is largely terrestrial and only flies relatively short distances.

Arambourgiania philadelphia (giant Pterosaurs) squabble over a small theropod dinosaur. Picture credit: Mark Witton.

Picture credit: Mark Witton

The research team’s results corroborated the findings of previous studies examining the flying abilities of Argentavis magnificens. They found that it was well suited to thermal soaring. In contrast, the team found that Pelagornis sandersi was better suited to thermal soaring, although earlier studies had proposed dynamic soaring.

To read Everything Dinosaur’s article from 2014 about the discovery of P. sandersi: The Largest Ever Flying Bird Pelagornis sandersi.

Everything Dinosaur’s recent article (May 2022), on Thanatosdrakon: The Dragon of Death.

The scientific paper: “How did extinct giant birds and pterosaurs fly? A comprehensive modeling approach to evaluate soaring performance” by Yusuke Goto, Ken Yoda, Henri Weimerskirch and Katsufumi Sato published in the PNAS Nexus.

The award-winning Everything Dinosaur website: Pterosaur Models.

Leave A Comment