The long neck of the giraffe has often been cited as a classic example of adaptive evolution. Long necks evolved to permit them to access food that other animals could not reach. However, a newly described early giraffe with a toughened skull adapted for head-butting contests suggests that intensive sexual competition may have led to the extremely long neck found in modern giraffes.

Discokeryx xiezhi from the Early Miocene (Junggar Basin)

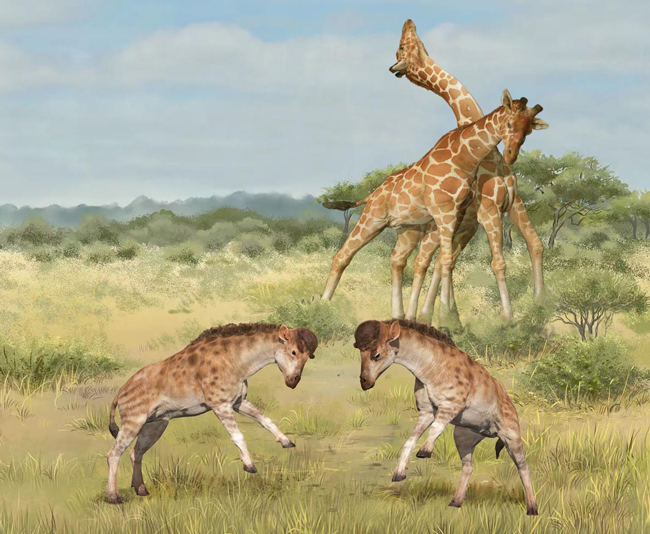

Scientists led by researchers from the Chinese Academy of Sciences have described a new species of ancient giraffe from the northern margins of the Junggar Basin in north-western China (Xinjiang Uygur Autonomous Region). The early giraffoid named Discokeryx xiezhi did not have a very long neck, instead, based on the analysis of an almost complete skull and four cervical vertebrae, this herbivore had a neck and head adapted to absorbing the immense stresses of head-butting combat.

Writing in the academic journal “Science”, the researchers conclude that the neck bones of Discokeryx xiezhi were extremely stout and had the most complex joints between the head and the neck and between the cervical vertebrae of any mammal. The team demonstrated that the complex articulations between the skull and cervical vertebrae of Discokeryx xiezhi were particularly adapted to high-speed head-to-head impact. They found this structure was far more effective than that of extant animals, such as musk oxen, that are adapted for head butting intraspecific combat. The scientists postulate that D. xiezhi may have been the vertebrate best adapted to head impact known to science.

Lead author of the study, Shi-qi Wang of the Chinese Academy of Sciences explained:

“Both living giraffes and Discokeryx xiezhi belong to the Giraffoidea, a superfamily. Although their skull and neck morphologies differ greatly, both are associated with male courtship struggles and both have evolved in an extreme direction.”

Climate Change Driving Morphological Changes

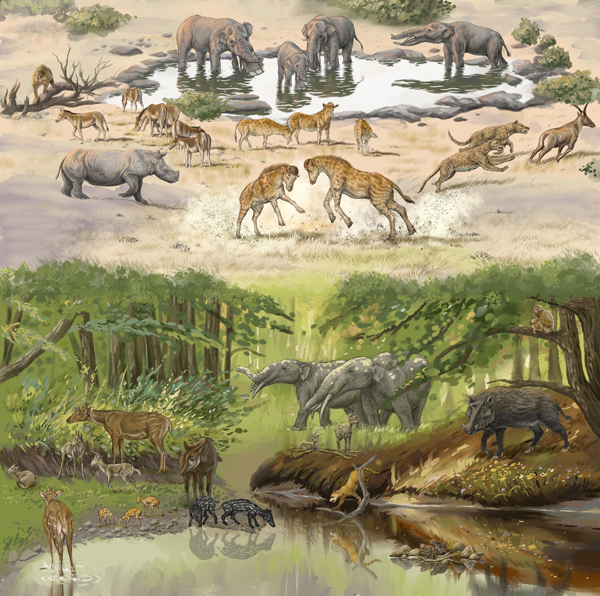

Tooth isotope analysis of fossil teeth indicate that Discokeryx lived in a dry, grassland environment. The habitat was more barren and less rich than forest environments and this may have resulted in increased stress on animal populations and greater competition within species for limited resources. Around 7 million years ago, the environment on the East African Plateau was broadly similar with forests being replaced by savannah. The direct ancestors of extant giraffes had to adapt and it is possible that during this period mating males developed a way of attacking their competitors by swinging their necks and heads. This extreme struggle, supported by sexual selection, thus led to the rapid elongation of the giraffe’s neck over a period of two million years to become the extant genus, Giraffa.

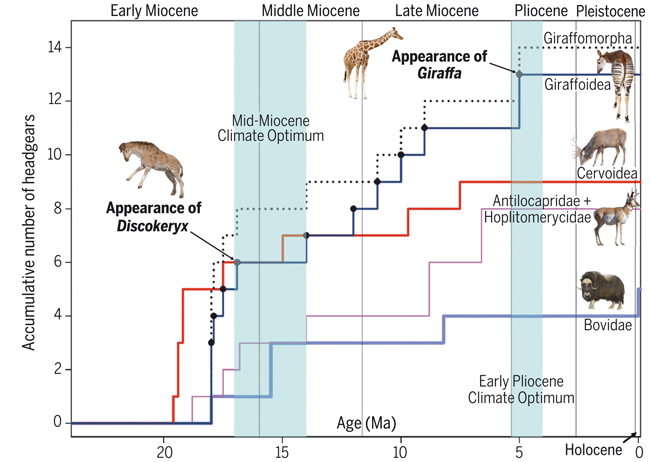

Comparing Horn Morphology

The research team compared the horn morphology of several groups of ruminants, including giraffoids, cattle, sheep, deer and pronghorns. They found that horn diversity in giraffes is much greater than in other groups, with a tendency toward extreme differences in morphology. This suggests that courtship struggles (intraspecific combat) are more intense and diverse in giraffes than in other ruminants.

The research team conclude that the primary driving force for extreme body shape in giraffes was not the benefit of being able to browse on parts of the canopy other herbivores could not reach, but it was the intensive sexual competition that fostered extreme morphologies.

Everything Dinosaur acknowledges the assistance of a media release from the Chinese Academy of Sciences in the compilation of this article.

The scientific paper: “Sexual selection promotes giraffoid head-neck evolution and ecological adaptation” by Shi-qi Wang, Jie Ye, Jin Meng, Chunxiao Li, Loic Costeur, Bastien Mennecart, Chi Zhang, Ji Zhang, Manuela Aiglstorfer, Yang Wang, Yan Wu, Wen-yu Wu and Tao Deng published in the journal Science.

The award-winning Everything Dinosaur website: Prehistoric Animal Models.

Leave A Comment