An analysis of fragmentary dinosaur fossil remains recovered from Lewisville Formation exposures around the Dallas/Fort Worth area of Texas have provided scientists with a fresh perspective on the theropod fauna of Appalachia during the Cenomanian stage of the Late Cretaceous. Around 95 million years ago, the extreme western edge of Appalachia was home to a variety of meat-eating dinosaurs including a tyrannosauroid and a larger carcharodontosaurid.

Theropods from Appalachia

Although the fossil remains consisting mainly of shed teeth and small portions of bone are highly fragmentary, the researchers are confident that this material confirms for the first time, the presence of a large carcharodontosaur allosauroid in Appalachia.

The researchers conclude that the Lewisville Formation theropod biota was similar in composition to contemporaneous deposits known from Laramidia. This confirms that theropod dinosaur communities were probably very similar across North America during the early Late Cretaceous and extends our knowledge regarding the non-avian dinosaur fauna of Appalachia shortly after the establishment of the Western Interior Seaway that divided the continent into two separate landmasses.

Picture credit: Julio Lacerdo

The researchers who included lead author Christopher Noto (University of Wisconsin-Parkside), examined fossils that had been recently collected from four sites in the Fort Worth/Dallas area of Texas as well as many specimens housed in museum collections.

They found that fossils representing a large-bodied carcharodontosaur and a mid-sized tyrannosauroid were present at a number of locations. This suggests that big, meat-eating dinosaurs roamed extensively over the delta represented by the Lewisville Formation deposits. The fossilised remains of much smaller theropods such as troodontids and dromaeosaurids were in contrast, restricted to just one or two sites.

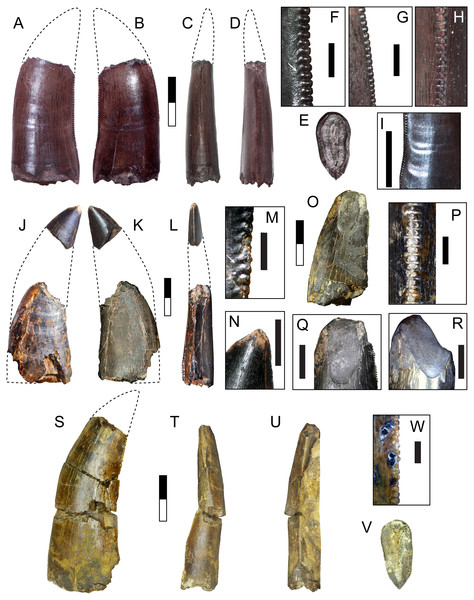

Teeth assigned to the Carcharodontosauria from the Lewisville Formation. Scale bars of unbordered images in A–E are 5 mm, (J)–(V) are 10 mm. Scale bars of bordered images are 1 mm. Picture credit: Noto et al.

Picture credit: Noto et al

The First Evidence of Tyrannosauroidea and Troodontidae in Appalachia

Whilst largely fragmentary, the researchers are confident that the material is sufficiently diagnostic to identify six or seven new taxa representing small, medium and large theropods. As well as recording the first carcharodontosaurid fossil material from Appalachia, the team concluded that there were also specimens representing the Tyrannosauroidea and Troodontidae too, the first occurrence of these groups in Appalachia.

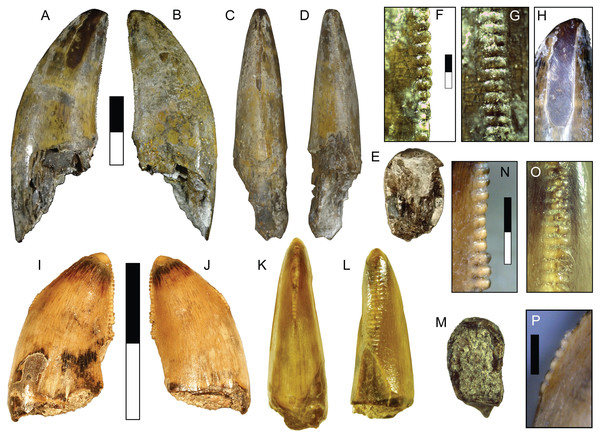

Teeth assigned to the Tyrannosauroidea from the Lewsiville Formation. Scale bars of bordered images are 1 mm, except P which is 0.5 mm. Picture credit: Noto et al.

Picture credit: Noto et al

Size Assessment Based on Komodo Dragon Tooth Research

The body size of each dinosaur was estimated using a formula based on the size of the serrations (denticles) found on the teeth of Komodo dragon lizards of various sizes, D’Amore and Blumenschine (2012). The researchers hope that more body fossils will be found to provide a clearer picture of the theropod biota of Appalachia during the early Late Cretaceous.

A List of the theropod taxa with maximum size based on Komodo dragon tooth comparisons stated:

- Carcharodontosauria maximum body length 5.7 metres*

- Tyrannosauridae maximum body length 4.8 metres*

- Dromaeosaurinae (a theropod potentially similar to Deinonychus or Utahraptor) maximum body length 5.1 metres*

- Dromaeosauridae maximum body length 1.9 metres*

- Troodontidae

- Coelurosauria maximum body length 1.6 metres*

- Indeterminate theropod maximum body length 2.6 metres*

Maximum body length* based on D’Amore and Blumenschine (2012).

Text in green indicates new taxa for Appalachia.

Transitional Fauna

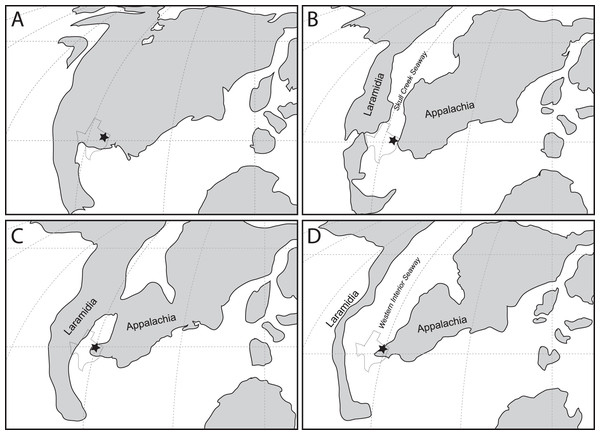

Comparison with other, roughly contemporaneous fossil assemblages across North America supports the presence of a cosmopolitan fauna throughout the Early Cretaceous. These theropod fossils from south-western Appalachia are remarkably similar to contemporaneous deposits known from Laramidia to the west. However, the opening up of the Western Interior Seaway led to a considerable divergence in the composition of dinosaur dominated terrestrial communities between Laramidia and Appalachia.

Palaeogeographic maps showing North America in the late Early Cretaceous and early Late Cretaceous (A) Albian stage approximately 110 million years ago, with (B) the late Albian approximately 105 million years ago. During the late Albian the first vestiges of the Western Interior Seaway began to form separating North America into two landmasses, Appalachia to the east and Laramidia to the west. Early Cenomanian approximately 100 million years ago, showing short-term regression of the shallow seaway that led to the two landmasses being connected once again. Finally (D), middle Cenomanian approximately 95 million years ago depicting the establishment of the Western Interior Seaway separating the landmasses once again. The black star marks the location of the Lewisville Formation. Maps redrawn from Scotese (2021). Picture credit: Noto et al.

Picture credit: Noto et al

By the Late Cretaceous distinctive dinosaur faunas had evolved on the two North American landmasses. The Lewisville Formation documents the transitional nature of Cenomanian coastal ecosystems in Texas while providing additional details on the evolution of Appalachian communities shortly after Western Interior Seaway extension. These fossils indicate that the faunal transition between Early and Late Cretaceous dinosaur groups was already underway around 95 million years ago (early-middle Cenomanian).

The scientific paper: “A newly recognized theropod assemblage from the Lewisville Formation (Woodbine Group; Cenomanian) and its implications for understanding Late Cretaceous Appalachian terrestrial ecosystems” by Christopher R. Noto, Domenic C. D’Amore, Stephanie K. Drumheller and Thomas L. Adams published in PeerJ.

Visit the Everything Dinosaur website: Dinosaur Toys.

Leave A Comment