New Study Suggests Late Cretaceous Southern United States Had “Raptors” Too

Dineobellator notohesperus – A Velociraptorine with Extra Attitude!

Scientists have described a new species of “raptor” from the Late Cretaceous of New Mexico. Described from fragmentary remains, this two-metre-long carnivore was related to Velociraptor. It may have been roughly the same size as the Mongolian genus, but it probably was even more agile with a stronger grip. Its discovery suggests that the dromaeosaurids were diversifying right up to the end of the Age of Dinosaurs.

Life Reconstruction Dineobellator notohesperus (Maastrichtian of New Mexico)

Picture credit: Sergey Krasovskiy

Dineobellator notohesperus

Writing in the academic journal “Scientific Reports”, the researchers from The University of Pennsylvania and the New Mexico Museum of Natural History and Science, describe a partial, skeleton excavated from the Bisti/De-na-zin Wilderness of New Mexico, found within a few metres above the base of the Naashoibito Member. The coarse sandstone deposits are notoriously difficult to date, these sediments were deposited towards the end of the Cretaceous between 70 and 66.3 million years ago (Maastrichtian faunal stage).

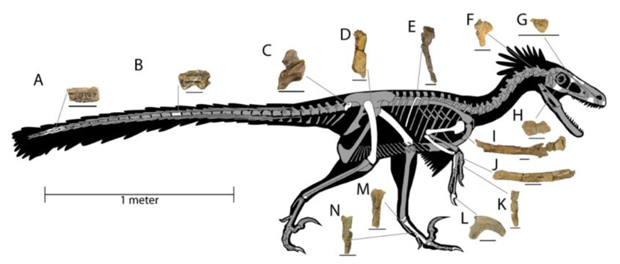

Fossil material includes parts of the skull, elements from the jaws, fragments of vertebrae, tail bones (caudal vertebrae), one rib with other pieces of rib and limb bones including a nearly complete right upper arm bone (humerus) and a nearly complete right ulna (bone from the forearm). The first fossilised remains were found in 2008, subsequent field work carried out in 2009, 2015 and 2016 yielded more fossil material, mostly very fragmentary in nature. It is believed all the fossil material, including a claw from the right hand, represents the remains of a single dinosaur.

A Skeletal Reconstruction of Dineobellator notohesperus

Picture credit: Jasinski et al/Scientific Reports

A Small but Dangerous Dinosaur

Dineobellator notohesperus is the first dromaeosaurid to be described from the southern United States. It would have lived in the south of the Cretaceous landmass of Laramidia. Although no evidence of feathers has been found, the ulna shows evidence of a row of small rounded pits in the bone, interpreted as anchor points for large feathers on the arm (ulna papillae). Analysis of the forelimbs suggest that Dineobellator had stronger arms with a more powerful grip. A study of the tail bones suggest that the tail had greater movement which would have made this dinosaur adept at making sharp turns and agile changes of direction.

The researchers suggest these anatomical traits provide an insight into how this small theropod hunted and behaved.

The researchers, which include Dr Steven Jasinski (Department of Earth and Environmental Science, University of Pennsylvania), postulate that Dineobellator was an active predator that occupied a discrete ecological niche in the food chain whilst living in the shadow of Tyrannosaurus rex.

The newest North American “raptor” Dineobellator notohesperus is pronounced dih-nay-oh-bell-ah-tor noh-toh-hes-per-us and the genus name comes from the native Navajo word “Diné”, a reference to the Navajo Nation and the Latin word “bellator” which means warrior. The trivial name has been erected to acknowledge the location of the fossil find. The word “noto” is from the Greek meaning southern and “hesper” the Greek for western. This is an acknowledgement that Dineobellator roamed the south-western part of the United States. In addition, Hesperus is a reference to a Greek god, the personification of the evening star (Venus) and by extension “western”.

Dr Jasinski has already had a considerable impact on the Dromaeosauridae family. Back in 2015, Everything Dinosaur reported on the formal description of Saurornitholestes sullivani, a dinosaur named by Steven Jasinski whilst a PhD student at the University of Pennsylvania. To read more about S. sullivani: Sniffing Out a New Dinosaur Species.

An Illustration of Saurornitholestes sullivani

Picture credit: Everything Dinosaur

A Tough Life for a Tough Dinosaur

A phylogenetic analysis undertaken by the research team places Dineobellator within the Velociraptorinae subfamily of the Dromaeosauridae. Other Maastrichtian “raptors” known from North America are few and far between (Acheroraptor and Dakotaraptor – both from the Hell Creek Formation). The discovery of Dineobellator suggests that dromaeosaurids were still diversifying at the end of the Cretaceous and as an velociraptorine, its fossils lend further weight to the idea that faunal interchange between Asian and North American dinosaurs took place sometime during the Campanian/Maastrichtian.

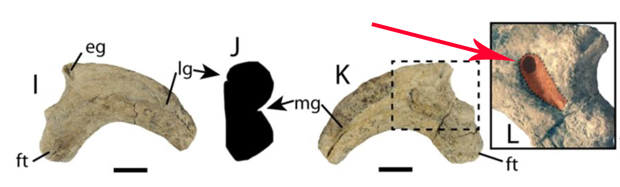

It is not known whether Dineobellator notohesperus was a pack hunter. The fossilised remains do indicate that this was one very tough dinosaur but it did not have everything its own way. A rib shows a deformity, suggesting that this bone was broken, but the animal suffered this trauma a while before it died as the break is healed. Intriguingly, the scientists identified a prominent gouge mark preserved on the hand claw (manual ungual). This gouge mark, which measures nearly a centimetre long, terminates in a small depression.

The scientists suggest that this damage was not caused by disease or by any process associated with the preservation of the fossil bones. The team suggest that this was an injury that occurred close to, or at the time of this dinosaur’s demise.

Injured in a Fight?

The researchers speculate that this Dineobellator received an injury in a fight with another Dineobellator or perhaps this damage to its hand claw was inflicted upon it by another type of predatory theropod.

Views of the Hand Claw of Dineobellator notohesperus Showing Damage Interpreted as a Wound Inflicted by Another Theropod Dinosaur

Picture credit: Jasinski et al/Scientific Reports with additional annotation by Everything Dinosaur

The scientific paper: “New Dromaeosaurid Dinosaur (Theropoda, Dromaeosauridae) from New Mexico and Biodiversity of Dromaeosaurids at the end of the Cretaceous” by Steven E. Jasinski, Robert M. Sullivan and Peter Dodson published in Scientific Reports.

The Everything Dinosaur website: The Everything Dinosaur Website.