Parmastega aelidae – Hunting Like a Crocodile

A fascinating new paper has just been published in the journal “Nature” that suggests that some of the very first animals with backbones that were capable of terrestrial locomotion may have never left the water. Instead, these creatures distantly related to animals that walk on land today, including ourselves, hunted rather like extant crocodiles and ambushed animals on the shore. That is the conclusion of a group of international scientists that have studied the fossils of Parmastega aelidae, a needle-toothed early tetrapod that lived around 372 million years ago.

A Tropical Lagoon 372 Million Years Ago – P. aelidae Hunting Behaviour

Picture credit: Mikhail Shekhanov for the Ukhta Local Museum

What are Tetrapods?

Tetrapods include all living and extinct amphibians, reptiles, birds and mammals. They are predominantly terrestrial, although some animals, whales for example, are entirely marine but had land-living ancestors. Most tetrapods have four limbs, although some such as snakes have lost their limbs, but evolved from four-limbed ancestors.

These types of animals evolved from lobe-finned fishes (Sarcopterygii), during the Middle to Late Devonian. Recent fossil discoveries have greatly increased the number of tetrapods known from Upper Devonian strata, but most genera are still only described from very fragmentary remains. Most of what palaeontologists know about this extremely important group of vertebrates is based on the better known and more complete fossil specimens representing Ichthyostega and Acanthostega.

A Life Reconstruction of the Late Devonian Tetrapod Ichthyostega

Picture credit: Julia Molnar

A Gap in the Fossil Record

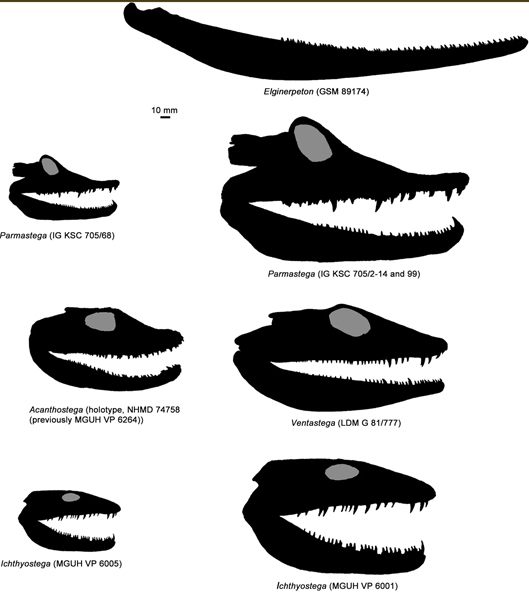

Trouble is, both Ichthyostega and Acanthostega along with the less complete but partly reconstructable genera Ventastega and Tulerpeton date from around 365-359 million years ago (late Famennian age of the Devonian), but palaeontologists have found tantalising fragmentary fossils that are at least ten million years older and the oldest known tetrapod footprints date from nearly 395 million years ago – read about their discovery here: Footprints from a Polish Quarry Suggest Land Vertebrates 35 Million Years Earlier than Previously Thought.

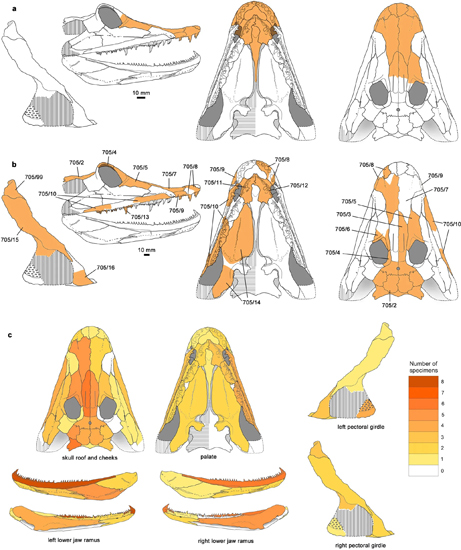

In this newly published paper, the researchers that include Jennifer Clack (University of Cambridge) and Pavel Beznosov (Russian Academy of Sciences), describe Parmastega aelidae, a tetrapod from Russia dated to the earliest Famennian age (about 372 million years ago), represented by three-dimensional material that enables the reconstruction of the skull and shoulder girdle.

The raised orbits, lateral line canals and weakly ossified postcranial skeleton of P. aelidae suggest a largely aquatic, surface-cruising animal. Phylogenetic analysis supported by Bayesian statistics indicates that Parmastega might represent a sister group to all other tetrapods.

Skull Bones of Parmastega – Numerous Skull Bones Have Allowed Palaeontologists to Reconstruct the Skull

Picture credit: Nature

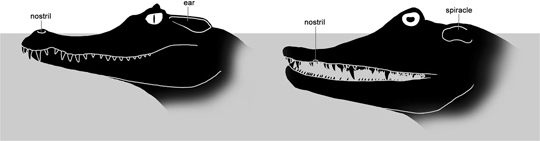

Parmastega aelidae Comparisons with a Crocodile

The fossil material representing several individual animals comes from north-western Russia. This area in the Late Devonian was a large tropical lagoon on a coastal plain, inhabited by many types of ancient fish including placoderms. The unusual suite of anatomical features identified in Parmastega include elasticated jaws, slender needle-like teeth and eyes located towards the top of the head so that it could keep a look out for prey whilst remaining almost totally submerged. These anatomical features are reminiscent to those found in today’s aquatic ambush predators such as crocodilians.

Comparing the Skull of Parmastega to that of a Caiman

Picture credit: Nature

The scientists also discovered that part of Parmastega’s shoulder girdle consisted of cartilage, and its vertebral column and paired limbs could also be made of cartilage, indicating it probably spent most or all its time in water. The large concentration of the fossil remains also suggests that it may have lived in large groups.

An Analysis of Sensory Canals

Co-author of the scientific paper, Professor Per Ahlberg (University of Uppsala, Sweden) stated that clues as to the lifestyle of Parmastega were found by analysing sensory canals identified in the fossil bones. These sensors probably helped Parmastega to detect vibrations in the water, a trait inherited from its sarcopterygian ancestors.

Professor Par Ahlberg stated:

“These canals are well developed on the lower jaw, the snout and the sides of the face, but they die out on top of the head behind the eyes. This probably means that it spent a lot of time hanging around at the surface of the water, with the top of the head just awash and the eyes protruding into the air. We believe there may have been large arthropods such as millipedes or ‘sea scorpions’ to catch at the water’s edge. The slender, elastic lower jaw certainly looks well-suited to scooping prey off the ground, its needle-like teeth contrasting with the robust fangs of the upper jaw that would have been driven into the prey by the body weight of Parmastega.”

Parmastega aelidae Fossils

Dr Marcello Ruta from the University of Lincoln, a co-author of the paper added:

“These fossils give us the earliest detailed glimpse of a tetrapod: an aquatic, surface-skimming predator, just over a metre in length, living in a lagoon. The evolution of tetrapods is one of the most important events in the history of backboned animals, and ultimately led to the appearance of our own species. Early in their history, tetrapods evolved many changes in their feeding strategies, movement abilities, and sensory perception, but many of these are still shrouded in mystery.”

Comparing the Head Morphology of Late Devonian Tetrapods

Picture credit: Nature

Everything Dinosaur acknowledges the assistance of a press release from the University of Lincoln in the compilation of this article.

The scientific paper: “Morphology of the earliest reconstructable tetrapod Parmastega aelidae” by Pavel A. Beznosov, Jennifer A. Clack, Ervīns Lukševičs, Marcello Ruta and Per Erik Ahlberg published in the journal Nature.

The Everything Dinosaur website: Everything Dinosaur.

Leave A Comment