Scientists find Kayentatherium wellesi Fossil Along with Young

The Order Mammalia has a number of distinguishing characteristics when compared to the other vertebrates. For example, mammals tend to have bigger brains and tend to produce some of the smallest numbers of offspring per litter. Mammals evolved from reptiles and at some point in their evolutionary history, larger brains developed and smaller broods became the norm. Scientists writing in the academic journal “Nature”, have published details of the discovery of the fossilised remains of a Jurassic stem mammal, one that was found in association with thirty-eight babies.

The fossilised specimens might help palaeontologists to work out how mammals developed a different approach to reproduction when compared to their reptilian ancestors.

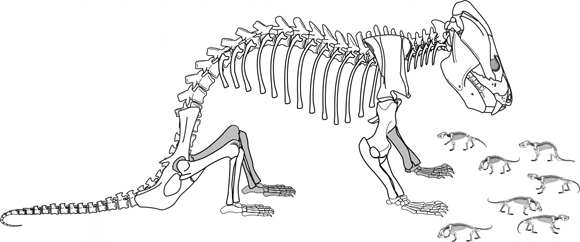

A Skeletal Reconstruction of the Probable Mother (Kayentatherium wellesi) and Offspring

Picture credit: Eva Hoffman/The University of Texas at Austin

Jurassic Stem Mammal Kayentatherium wellesi

The fossils represent Kayentatherium wellesi, a cynodont, it was only as the specimen was being prepared that the researchers realised that this was an exceptional fossil. The find of a 185-million-year-old K. wellesi with offspring are the only known fossils of baby stem mammals with what is believed to the mother.

The presence of so many offspring, probably only recently hatched from their eggs when they died, indicates that these types of stem mammal had litters more than twice the size of any living member of the Mammalia. The size of the brood is akin to the breeding strategy of extant reptiles

Lead author of the study, Eva Hoffman (who studied the fossils whilst a graduate student at the University of Texas at Austin), commented:

“These babies are from a really important point in the evolutionary tree. They had a lot of features similar to modern mammals, features that are relevant in understanding mammalian evolution.”

The Kayenta Formation of Arizona

Hoffman co-authored the study with her graduate adviser, Jackson School Professor Timothy Rowe, who collected the specimen during fieldwork exploring the Early Jurassic sediments of the Kayenta Formation in Arizona, more than eighteen years ago.

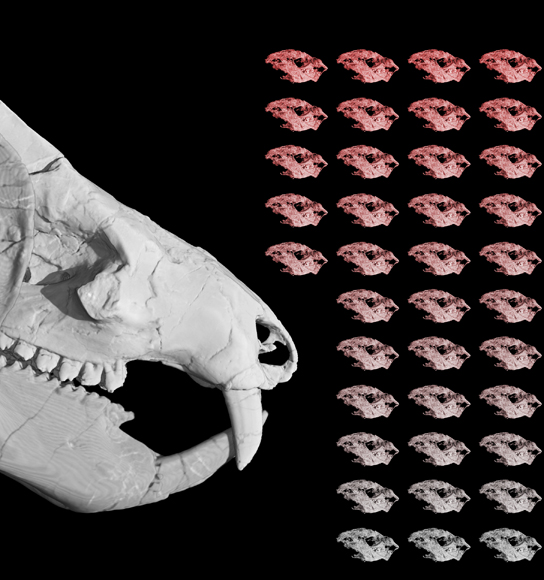

Computerised tomography was used to reveal the bones inside the matrix back in 2011. However, advances in CT-scanning finally permitted researchers at the University of Texas at Austin to reveal the babies, including complete skulls and partial postcranial material.

Advances in Computerised Technology Over the Last Seven Years Permitted the Fine Details of the Babies to be Discerned

Picture credit: Eva Hoffman/The University of Texas at Austin

The Skulls of the Babies – The Same as the Adult’s Only Smaller

The highly detailed computer-generated images permitted the researchers to verify that the tiny bones were Kayentatherium wellesi, the same as the adult. The analysis revealed that the skulls were scaled-down replicas of the adult, only ten percent the size of an adult skull, but otherwise proportional. This contrasts with extant mammals, as their babies are born with shortened faces and large skulls to accommodate a big brain. The brain of mammals is a very energy demanding organ, for example, in humans the brain needs more energy than any other organ of the body.

It has been estimated that the brains of human beings require around 20% of the total energy needed by our bodies each day. Breeding and producing offspring also requires a lot of energy. The discovery that Kayentatherium, a stem mammal, had a tiny brain and many babies, despite otherwise having much in common with extant mammals, suggests that a critical step in the evolution of the Mammalia was trading large litters for large brains. This evolutionary change is therefore likely to have taken place more recently than 185 million-years-ago.

Professor Rowe explained:

“Just a few million years later, in mammals, they unquestionably had big brains and they unquestionably had a small litter size.”

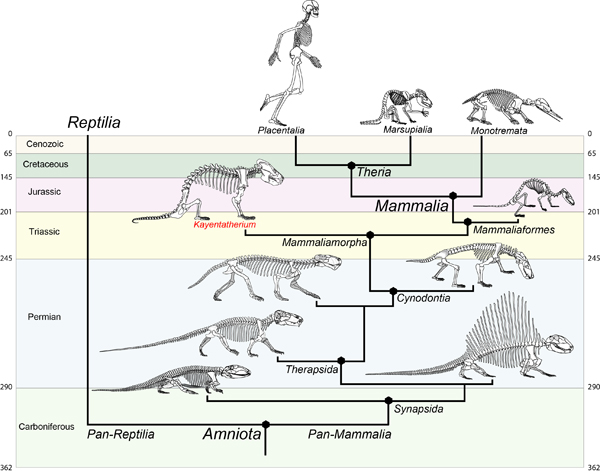

Where does the Jurassic Stem Mammal Kayentatherium Sit on the Mammalian Evolutionary Tree?

Kayentatherium was very probably endothermic (warm-blooded) and the skeleton shows a number of anatomical traits associated with modern mammals.

The Place of Kayentatherium on the Mammalian Family Tree

Picture credit: Eva Hoffman/The University of Texas at Austin

The mammalian approach to reproduction directly relates to our own species development (Homo sapiens), including the development of our own brains. By looking back at our early mammalian ancestors, we can learn more about the evolutionary process that helped shaped the development of humans.

Professor Rowe added:

“There are additional deep stories on the evolution of development and the evolution of mammalian intelligence and behaviour and physiology that can be squeezed out of a remarkable fossil like this now that we have the technology to study it.”

The scientific paper: “Jurassic Stem Mammal Perinates and the Origin of Mammalian Reproduction and Growth” by Eva A. Hoffman and Timothy B. Rowe published in Nature.

Everything Dinosaur acknowledges the assistance of a press release from the University of Texas at Austin in the compilation of this article.

The Everything Dinosaur website: Everything Dinosaur.

Leave A Comment