Kapes bentoni Saved by a Scan

The fossilised remains of a little reptile that roamed the land we now know as Devon has helped make links with the prehistoric vertebrate fauna of the Middle Triassic of Russia. Thanks to the use of computerised tomography (CT) scans, palaeontologists have had the rare opportunity to study the skull and postcranial elements of a procolophonid reptile. The fossil was found by co-author of the scientific paper, Dr Rob Coram of Swanage in November 2014, from a foreshore exposure of the Pennington Point Member of the Otter Sandstone Formation located close to the town of Sidmouth on the south Devon coast.

The Triassic sandstone deposits in these cliffs, which ironically form part of the famous UNESCO World Heritage site the “Jurassic Coast” contain vertebrate remains, but they are quite rare and often show signs of extensive weathering and transportation prior to burial and fossilisation.

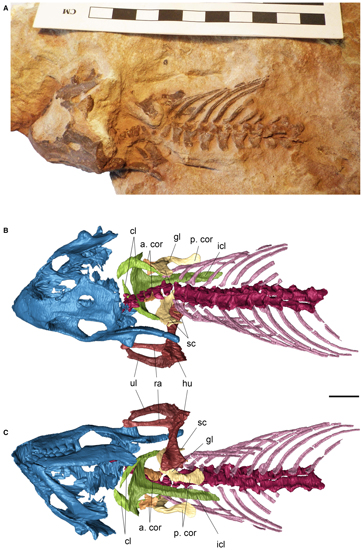

The Fossil Specimen (BRSUG 29950-13) and Two Computer Generated Images

Picture credit: Bristol University/Papers in Palaeontology

Procolophonid Reptiles (Procolophonidae)

The reptile has been identified as an example of Kapes bentoni, several species are included in this genus, all of which, including the type species K. amaenus, which was named in 1975, come from Russia. Procolophonids looked superficially like lizards, but they are not closely related to the Squamata. They are parareptiles, which evolved in the Permian and had a wide distribution during the Triassic, before becoming extinct shortly before the Triassic came to an end. When Dr Coram tried to clean and prepare the fossil, he found that the fossil material was too fragile and conventional preparation techniques would have resulted in permanent damage to the fossil bones.

Dr Coram commented:

“I tried everything I could. I have had a lot of experience of removing rock from fossils using a fine needle and working under the microscope, but this was a nightmare. When I touched it with a needle, small pieces of bone fell off.”

CT Scanning the Devon Fossil

In order to allow the fossil to be studied, Dr Coram contacted colleagues at Bristol University and a CT scan of the small fossil was organised. The job of interpreting the scans and the resulting computer generated images was given to PhD student Marta Zaher, who was at the Bristol University for a few months, normally she is based in Zagreb (Croatia). The three-dimensional scans of the skull and postcranial material turned out to be far better than the scientists had hoped. Even wear facets on the tiny teeth of the Kapes specimen could be discerned and studied.

Once all the scans had been compiled the researchers could examine the procolophonid fossil in great detail. Most of the procolophonid fossils from England are highly fragmentary, but the scans revealed the presence of a skull, cervical vertebrae, the shoulder girdle, forelimbs and the front half of the torso.

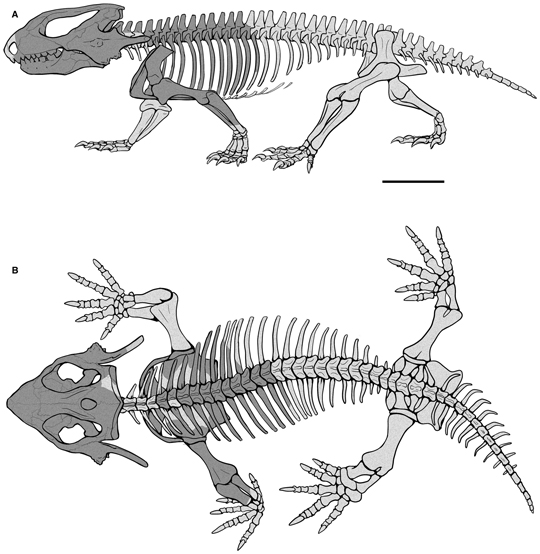

An Illustration of the Skeleton of Kapes bentoni (Lateral and Dorsal Views)

Picture credit: Bristol University/Papers in Palaeontology

Spectacular CT Scans of a Triassic Specimen

Student Marta explained:

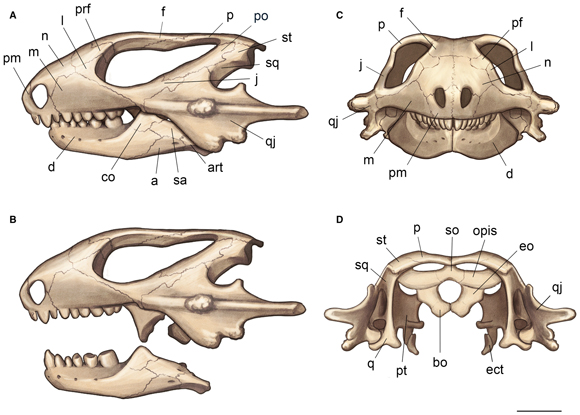

“The scans are amazing. They show every detail of the tiny, five-centimetre (two inch) long skull. You can see each tooth, and even the wear patterns. Almost all the tiny bones of the palate and braincase are there.”

She added:

“This identifies the animal without question as a procolophonid. These lived worldwide at the time, and they were important plant-eaters, with broad teeth fused to their jaws, and which wore down under grinding from the tough plant food.”

Several years ago, less complete specimens of the procolophonid had been found in the Devon rocks, and two academics then at the University of Bristol, Patrick Spencer and Glenn Storrs, had suggested the Devon animal was the same as Kapes from central Russia.

A spokesperson from Everything Dinosaur commented:

“Thanks to the use of computerised tomography, the researchers were able to get an unprecedented insight into the anatomy of an anapsid. This non-destructive technique has helped scientists to identify that this Devon specimen is very closely related to other reptiles, fossils of which come from the terrestrial red beds of Russia.”

A Diagram of the Skull Produced from the CT Scan Data

Picture credit: Bristol University/Papers in Palaeontology

Co-author of the scientific paper published in “Papers in Palaeontology”, Professor Mike Benton (Bristol University) stated:

“The new study confirms that the two animals are very close relatives, two species of the genus Kapes. This is most unusual, to have evidence of a biogeographic connection over thousands of kilometres. In the Middle Triassic, there was dry land in the UK and in Russia, but the area in between was filled with the Muschelkalk Sea, covering Germany and much of central Europe.”

Kapes bentoni

Many of the early procolophonids were insectivorous, however, Kapes bentoni was a plant-eater. This idea is reinforced by the heavy wear on the teeth as observed in the CT scans from this study. K. bentoni had a short, stocky body and it may have been fossorial (lived in a burrow). The spines on the skull have provided the scientists with a bit of a puzzle. It has been suggested that these spines had a defensive function, making the reptile seem bigger and more intimidating to a potential predator. The spines would also have obstructed any predator attempting to swallow Kapes head-first.

A Life Reconstruction of the Procolophonid Kapes bentoni

Picture credit: Marta Zaher

The scientific paper: “The Middle Triassic Procolophonid Kapes bentoni: Computed Tomography of the Skull and Skeleton” by Marta Zaher, Robert A. Coram and Michael J. Benton published by Papers in Palaeontology.

Everything Dinosaur acknowledges the assistance of a press release from Bristol University in the compilation of this article.

The award-winning Everything Dinosaur website: Everything Dinosaur.

Leave A Comment