A Reappraisal of our Closest Cousin

The Neanderthal (Homo neanderthalensis) is our closest relative on the hominin family tree. As our own genome has become better understood, geneticists and anthropologists have been able to appreciate just how closely related we are to Neanderthals.

However, since the first description of the Neanderthal (based on fossil remains from the Neander Valley in Germany), back in 1863, H. neanderthalensis has had quite a bad press. For most of the last 150 years or so, since we have known about this hominin species, the Neanderthals have been depicted as dim-witted, brutal ape-men. We now live in more enlightened times, our perception of the Neanderthal has changed. There is considerable evidence to indicate that this species of human, one that died out around 28,000 years ago, just a blink in geological time, was smart, strong and had a sophisticated culture.

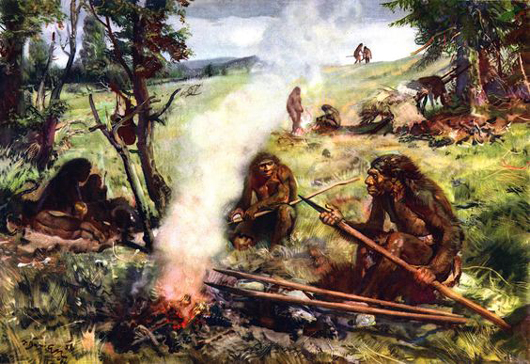

Many 20th Century Artists Depicted Neanderthals as “Ape-men”

Picture credit: Zdenek Burian

Neanderthals May Have Used Plants as Medicine

In a new study, published this week in the journal “Nature”, researchers from the University of Liverpool in collaboration with colleagues from the University of Adelaide’s Australian Centre for Ancient DNA (ACAD) and Dental School suggest that Neanderthals may have had quite a remarkable knowledge of medicine, even using penicillin, some 40,000 years before Sir Alexander Fleming. An analysis of ancient DNA found in the dental plaque of Neanderthals has provided further evidence that this species of hominin was intelligent and resourceful, using plant-based medicines and moulds to treat a variety of complaints.

The research also reveals dietary differences between different Neanderthal populations.

Commenting on the study, lead author Dr Laura Weyrich (ACAD) stated:

“Dental plaque traps micro-organisms that lived in the mouth and pathogens found in the respiratory and gastrointestinal tract, as well as bits of food stuck in the teeth, preserving the DNA for thousands of years. Genetic analysis of that DNA ‘locked-up’ in plaque, represents a unique window into Neanderthal lifestyle, revealing new details of what they ate, what their health was like and how the environment impacted their behaviour.”

Partial Neanderthal Skull Showing Jaw Bones

Picture credit: University of Liverpool

The scientists analysed and evaluated dental plaque samples from four Neanderthals found at the cave sites of Spy (Belgium) and El Sidrón (Spain). The four samples range in date from 50,000 years ago to 42,000 years ago approximately. The samples represent the oldest dental plaque to be genetically analysed.

The Spy Cave Neanderthals were found to have a largely carnivorous diet, consuming Coelodonta (Woolly Rhinoceros), wild sheep and foraged mushrooms. In contrast, the Neanderthals from the El Sidrón Cave site, showed no evidence of meat consumption, appearing to have had a largely vegetarian diet, consisting of moss, tree bark, mushrooms and pine nuts.

A spokesperson from Everything Dinosaur commented:

“Based on this dietary information, it can be assumed that these two groups of Neanderthals had very different lifestyles. One group seem to have been active hunters, trapping, ambushing and killing animals, whilst the other group seem to have been foragers within a forest environment. The dental plaque analysis leads to the inference that different groups of Neanderthals had different behaviours and ultimately, different strategies for survival.”

Surprising Self-medication

Evidence for self-medication was detected in an El Sidrón Neanderthal with a dental abscess (identified from scarring left on the jaw), this individual (most likely a male), also suffered from a chronic gastrointestinal pathogen (Enterocytozoon bieneusi). He would have been suffering from a severe bought of diarrhoea. The intestinal parasite was identified through studying DNA in the ancient dental plaque. However, further analysis revealed that he had been chewing the bark of the Poplar tree, which contains the natural pain killer salicylic acid (the active ingredient in modern aspirin). The scientists could also detect a natural antibiotic mould (Penicillium) not found in the other Neanderthals examined within this study.

From this, the team concluded that Neanderthals may have possessed a substantial knowledge of medicinal plants and their various anti-inflammatory and pain-reliving properties.

One of the researchers stated:

“Our findings contrast markedly with the rather simplistic view of our ancient relatives in popular imagination.”

The El Sidrón Neanderthal provided another intriguing insight into our Neanderthal evolutionary relationship. It seems that we shared several disease-causing microbes, including the bacteria that cause gum disease and dental caries. The scientists were able to identify the oldest microbial genome yet sequenced, a gum rotting bacteria called Methanobrevibacter oralis. The microbial genome is estimated to be around 48,000 years old.

The researchers also noted how rapidly the oral microbial community has altered in recent history. The composition of the oral bacterial population in Neanderthals and both ancient and modern humans correlated closely with the amount of meat consumed in the diet, with the Spanish Neanderthals grouping more closely with chimpanzees and our forager ancestors in Africa. The Belgian Neanderthal bacteria, in contrast, were similar to early hunter gatherers, and quite close to modern humans and early farmers.

Dental plaque and its microbial treasures are providing an extraordinary window on the past, giving geneticists and anthropologists new ways to explore and understand our evolutionary history through the micro-organisms that lived in us.

Visit the Everything Dinosaur website: Everything Dinosaur.

Leave A Comment