Fossil Footprints Hint at Decline of Amphibians

The Rise of Reptiles as the World Dried Up

Places like the “Jurassic Coast” of Dorset, or the beaches that surround Whitby (North Yorkshire), might be synonymous with fossil hunting, but surprisingly, even some of our great cities can lay claim to be at the centre of palaeontological research. Take the city of Birmingham (West Midlands), for example, not the sort of place that one would immediately associate with fossils (the exception being the amazing Wren’s Nest site to the north-west of Birmingham, Britain’s first national nature reserve for geology).

Fossil Footprints Studied

However, the study of a series of sandstone slabs, excavated from a quarry a few miles to the north of the centre of Birmingham is helping palaeontologists to plot global climate change some 310 million years ago, that led to the demise of amphibians and provided ideal conditions for the evolution and radiation of reptiles.

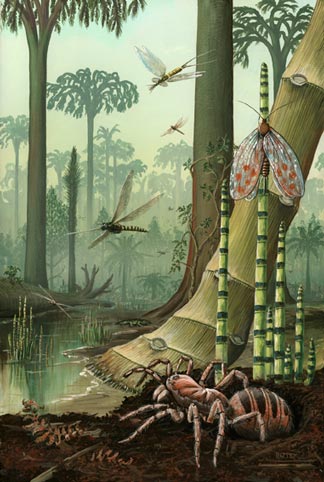

Birmingham, Like Most of the British Isles was once Covered in a Lush Tropical Carboniferous Rainforest

By the Carboniferous the insects were already highly diversified and the lush forests and swamps were dominated by Temnospondyls (primitive amphibians).

Picture credit: Richard Bizley (Bizley Art) for more of Richard Bizley’s artwork visit: Bizley Art.

In 1912, schoolteacher and amateur botanist Walter Henry Hardaker presented a paper to the Geological Society of London detailing the discovery of a series of tetrapod footprints and trackways that he had discovered in a quarry located in the village of Hamstead. Hamstead, itself has long since been swallowed up in the urbanisation of the area as the city of Birmingham expanded. The quarry too, has gone covered up as houses, shops and offices were built, after all, the quarry was located just a stone’s throw from Hamstead railway station.

The sandstones became part of the Lapworth Museum of Geology’s fossil collection at the University of Birmingham. Hardaker, an alumnus of Birmingham University, probably would have been fascinated by the recent research work undertaken by third-year Palaeobiology and Palaeoenvironments MSci student Luke Meade (University of Birmingham) and colleagues as they applied 21st century analytical techniques to reveal a glimpse of the world when reptiles were beginning to take over from the amphibians as the dominant tetrapods.

Funded by the Palaeontological Association

Using funding provided by the Palaeontological Association, the students scanned the twenty or so red sandstone slabs using state-of-the-art photogrammetric technology to provide a three-dimensional analysis of each track. Colour coding of the images permitted the research team to produce topographic maps showing the individual contours of each specimen. These three-dimensional images were then compared to other ichnofossils (trace fossils) to identify the types of animals which produced the footprints.

The footprints and tracks provide a remarkable insight into vertebrate life during the Pennsylvanian Epoch of the Late Carboniferous. These trace fossils were formed as animals crawled over soft mud next to river channels. A subsequent flood event covered these tracks with sand and helped to preserve snapshots in deep time. The red sandstone slabs preserve amazing details, not only of the footprints and tracks but also raindrops and cracks in the mud that were formed as the area dried out.

To read an article on Carboniferous fossils from North Wales: Tropical North Wales 300 Million Years Ago.

The research on these trace fossils indicates that the most common tracks were formed by amphibians, ranging from just a few centimetres in length (Batrachichnus salamandroides) to more than a metre long Limnopus ichnospecies).

Different Creatures Left Trace Fossils

Other types of creature traversed the mud, leaving their tracks, animals such as large pelycosaurs (synapsids distantly related to modern mammals). Although the tracks are much less common, their presence indicates that monitor lizard-sized Reptiliomorphs also roamed the swamps and low lying forest that was eventually to become the West Midlands of England.

The three-dimensional models of the footprints that the team were able to recreate, led to the identification of these tracks having been made by the ichnogenus Dimetropus. Smaller reptilian tracks were identified as having been made by sauropsid reptiles, (Dromopus lacertoides), whose descendants gave rise to the crocodiles, marine reptiles, pterosaurs, dinosaurs and birds.

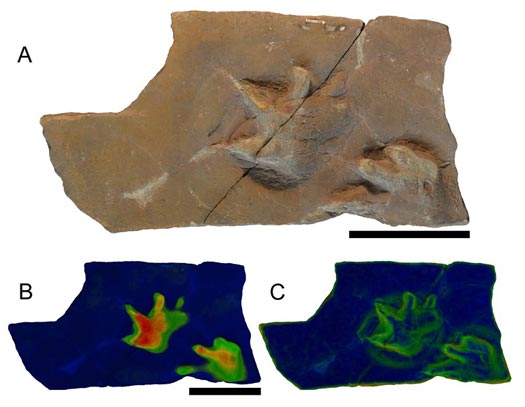

Limnopus Trace Fossils Used in the Study

Picture credit: University of Birmingham/PeerJ

The photograph above shows a well-defined example of Limnopus isp tracks from the Hamstead quarry. The top photograph shows a dorsal view of the fossil material, (B) tracks rendered to show relief with an arbitrary scale, whereas, (C) shows tracks rendered to highlight areas of steep gradient, digitally isolating the outline of the tracks to aid genus recognition and cross comparison.

Scale bar = 10 cm.

For replicas and models of Palaeozoic creatures: Prehistoric Life Models from CollectA.

The Hamstead Trace Fossils

This ichnofauna associated with the Hamstead trace fossils contrasts with the slightly stratigraphically older, more extensive and better-studied assemblage from Alveley (Shropshire), which is dominated by small amphibians with relatively rare Reptiliomorphs and Dromopus tracks are absent. The presence of Dromopus lacertoides at Hamstead, identified from this new study supports the theory that the world was gradually becoming more arid through the Late Carboniferous and different types of reptile were beginning to flourish.

Batrachichnus salamandroides Tracks Preserved in the Red Sandstone of Hamstead Quarry

Picture credit: University of Birmingham/PeerJ with additional annotation by Everything Dinosaur

In the picture above, tracks made by the amphibian Batrachichnus salamandroides are shown, the red line indicates the direction of travel, the long thin lines are tail drag marks.

As the world become drier, so those animals that did not have such a reliance on water compared to the amphibians would have had a distinct advantage. The synapsids and the diapsids being amniotes (they lay eggs on land or retain a fertilised egg within the female), would have had a significant evolutionary advantage over the amphibians that relied on returning to water to reproduce.

The scientific paper: “A Revision of Tetrapod Footprints from the Late Carboniferous of the West Midlands, UK” (PeerJ).

The Everything Dinosaur website: Everything Dinosaur.