Tooth Reveals New Dog Species

A PhD student at the University of Pennsylvania has identified a new species of prehistoric dog based on the analysis of a single tooth found by an amateur fossil hunter exploring a beach on the Maryland coast. The tooth provides new evidence to help support the scarce fossil record of carnivores from the Middle Miocene of eastern North America and it extends the fossil record of these types of canids in the United States by several million years.

Fossil Dog

An Illustration of a Prehistoric Dog Similar to the New Species (Cynarctus wangi)

Picture credit: Mauricio Antón from “Dogs, Their Fossil Relatives and Evolutionary History.”

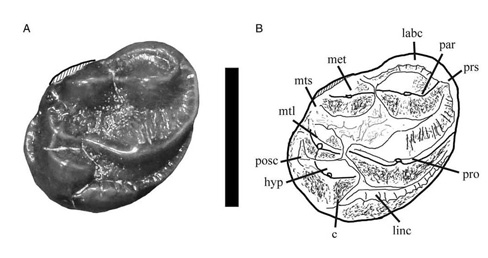

Fossil Tooth from a Prehistoric Dog

The fossil tooth, thought to be second molar from the right side of the upper jaw. comes from a type of prehistoric dog that would have been roughly the same size as an English Springer Spaniel. It was a member of the extinct subfamily of the Canidae called the Borophaginae. These dogs are referred to as “bone crushing dogs” as they possessed short, but very strong jaws and they probably could deliver a very powerful bite. The species name erected honours Xiaoming Wang, the Curator at the Natural History Museum of Los Angeles County and an expert on extinct mammalian carnivores of the northern hemisphere.

Lead author of the scientific paper published in the “Journal of Paleontology”, student Steven Jasinski, explained the shape of the dog’s jaw:

“In this respect they are believed to have behaved in a similar way to hyenas today.”

The Choptank Formation

The fossil tooth was found on a beach which underlies cliffs representing the Choptank Formation, (part of the Chesapeake Group), it was stored at the Smithsonian Institute. Measuring a little over one centimetre in length it had not been studied in great detail, however, the fine details on the surface of the tooth (the biting surface) enabled the researchers to distinguish this tooth from the fossils of another, older member of the Borophaginae known as Cynarctus marylandica.

A Picture and Accompanying Line Drawing Showing the Fossil Tooth

Picture credit: The University of Pennsylvania/Journal of Paleontology

Working in collaboration with co-author Professor Steven C. Wallace (East Tennessee State University), Jasinski was able to establish that their initial assumption about the tooth being from an already described species of prehistoric dog was incorrect.

Tooth Indicated a New Species

They had presumed that the tooth represented material from another borophagine dog called Cynarctus marylandica, fossil teeth of which had been found in the same area but from much older strata (the Calvert Formation, also part of the Chesapeake Group). C. marylandica is only known from teeth associated with the lower jaw. It was when the researchers compared the features on the occlusal surfaces (the biting surfaces) of the teeth, where the top and bottom teeth would have met, they found significant differences, enough to suggest that, in all probability this tooth from the upper jaw was an entirely new species.

Speculating on the importance of their research, Steven Jasinski said:

“It looks like it might be a distant relative descended from the previously known borophagine.”

The Demise of the Borophaginae

Once widespread in North America, the fossil record of the Borophaginae covers a period of approximately twenty-eight million years (Oligocene Epoch to the Late Pliocene). Once a diverse sub-family of the Canidae, represented by numerous species, it seems that the migration of predatory cats into North America from Asia along with the evolution of modern canids, the ancestors of today’s wolves and domestic dogs may have led to the decline and eventual extinction some 2.5 million years ago.

The shape of the tooth and from what has been inferred from other borophagine fossil material, it is likely that this prehistoric dog was not entirely reliant on meat to sustain itself.

The student stated:

“Based on its teeth, probably only about a third of its diet would have been meat. It would have supplemented that by eating plants or insects, living more like a mini-bear than like a dog.”

PhD Student Steven E. Jasinski Working on a Fossil Site

Picture credit: The University of Pennsylvania

This new borophagine canid expands the sparse fossil record of this group in north-eastern North America and extends further our knowledge of the fossil record of terrestrial taxa in the eastern part of the United States. The PhD student explained that most of the vertebrate fossils associated with this strata represent marine animals as they have a higher probability of becoming fossilised than land animals. He explained that fossil finds such as this tooth, are very rare but they help scientists to understand more about the terrestrial ecosystems that existed during Miocene Epoch.

Ancient dog fossils have not been the sole preoccupation of the student from the Dept. of Earth and Environmental Sciences, last year Everything Dinosaur reported on Steven’s research that led to the identification of a new type of North American predatory dinosaur: Sniffing Out a New Dinosaur Species.

I found this in a quarry that I worked at after we finished blasting a rock wall down. I’m not sure how many hundred feet down it actually out of after we took to wall down. The quarry is in northeast Pennsylvania.