Ancient Mom – Oldest Brood of Preserved Embryos Found

Evidence of Survival Strategies – Caring for Young (Waptia fieldensis)

The Cambrian was a critical time in the history of life on our planet and the Burgess Shale deposits of British Columbia have helped scientists to piece together a lot of data on the diverse marine fauna that evolved during this geological period. Some sophisticated survival strategies have been identified, including the earliest evidence recorded of brood care in an invertebrate. A research paper published this month details the discovery of a shrimp-like creature with about two dozen eggs preserved with embryos inside its body, making it the earliest example of brood care with preserved embryos in the fossil record.

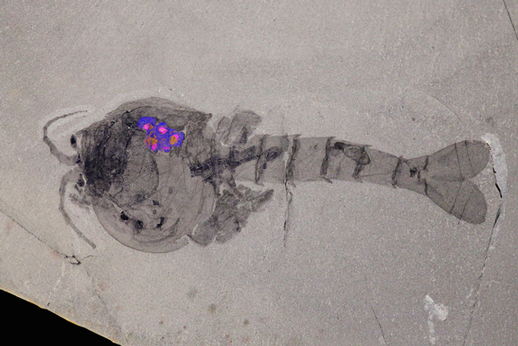

Waptia fieldensis Fossil Scanning Electron Microscope

Picture credit: Royal Ontario Museum

Waptia fieldensis

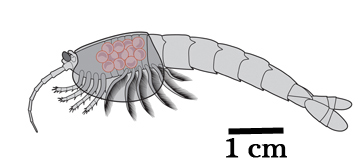

The marine arthropod known as Waptia fieldensis is one of the more abundant fossils to be found preserved in the rocks that mark the location of the Burgess Shales. The animal was named and scientifically described in 1912 by the great Charles D. Walcott, the American geologist who discovered the Burgess Shale deposits back in 1909. The fossils preserve the fauna of the Middle Cambrian (about 508 million years ago), in exquisite detail.

The research team was composed of scientists from the Royal Ontario Museum (Toronto) and the Université Claude Bernard (Lyon, France), they examined a total of 979 Waptia specimens from the Royal Ontario Museum’s own extensive Burgess Shale fossil collection and a further 866 specimens housed at the Smithsonian Institution National Museum of Natural History (Washington D.C.). From this sample, the team identified five fossils from the Canadian collection that contained eggs.

An Illustration of Waptia fieldensis

Picture credit: Royal Ontario Museum

Looking after the young, including carrying the eggs or juveniles is a form of parental care. This is a survival strategy as it enhances the offspring’s chances of becoming an adult. Rather than abandoning the eggs, these little creatures, which are distantly related to extant crabs, lobsters and shrimps, gave their babies a better chance of survival. The implication is that there were a large number of predators around who would have happily consumed the young and therefore a strategy such as this would have made sense within a complex food web.

For models and replicas of Palaeozoic invertebrates and other prehistoric animals: CollectA Prehistoric Life Models.

When Did Parental Care Arise?

One of the outstanding questions in palaeontology is at what point did such brood care strategies arise? Parental care is known to have evolved independently in a number of different types of animal, it has been thought that such strategies evolved as a response to predation pressure, a harsh environment or an environment where resources such as food and shelter were not consistently available (ephemeral resources).

Lead author of the academic paper, Jean-Bernard Caron, (Curator of Invertebrate Palaeontology, Royal Ontario Museum) stated:

“As the oldest direct evidence of a creature caring for its offspring, the discovery adds another piece to our understanding of brood-care practices during the Cambrian explosion, a period of rapid evolutionary development when most major animal groups appear in the fossil record.”

Co-author Jean Vannier (Senior Researcher at the Université Claude Bernard), added:

“This creature is expanding our perspective on the diversification of brood care in early arthropods.”

A Fossil of Waptia fieldensis (Burgess Shale)

Picture credit: Royal Ontario Museum

Eggs Held in Place on the Underside of the Carapace

The clusters of eggs were held in place on the underside of the carapace, significantly all the specimens carrying embryos showed small clutch sizes. Up to twenty-four eggs were recorded per specimen, the eggs were also relatively large compared to many extant arthropod species (egg size over 2 mm). It seems that this ancient arthropod evolved a breeding strategy that involved the production of fewer offspring but the low numbers were balanced by the greater degree of parental care shown.

In simple terms, some arthropods produce many hundreds of eggs but these are scattered and left to drift, to fend for themselves, what we at Everything Dinosaur call this a “blunderbuss” approach to reproduction. If only two or three of these eggs make it to adulthood and breed then the survival of the species is secured for at least another generation. However, W. fieldensis seems to have adopted a different strategy, investing more time, energy and care per embryo, a sort of “rifle” approach to reproduction.

Different Parental Strategies Observed in Cambrian Fossils

The strategy adopted by W. fieldensis is in contrast with the arthropod called Kunmingella douvillei from the Chengjiang biota (ca. 515 million years ago). K. douvillei fossils from China, show that this nektonic animal had a high number of small eggs. No embryos have as yet, been identified in the Chinese fossil material. As Waptia fieldensis lived some 7 million years after Kunmingella douvillei, it suggests that there was a rapid evolution of a variety of modern-type life-history traits, including a greater investment in offspring survivorship, soon after the Cambrian explosion.

Jean Vannier explained:

“The relatively large size of the eggs and the small number of them [in W. fieldensis] contrasts with the high number of small eggs found previously in another bivalved arthropod, known as Kunmingella douvillei. And though that creature predates Waptia by about 7 million years, none of its eggs contained embryos.”

The fact that W. fieldensis and K. douvillei carried their eggs in different ways hints that brood care evolved in a number of directions during the Cambrian period. In addition, the bivalved carapace likely played an important role in arthropods’ brood care, as researchers have already noted the structure’s presence in egg-carrying Middle Ordovician ostracods dating to 450 million years ago.

The study was published online Dec. 17 in the journal Current Biology.

Visit Everything Dinosaur’s award-winning website: Everything Dinosaur.