Fossilised Spermatozoa from Ancient Annelid

Dinosaurs and other large vertebrates might grab all the headlines when it comes to fossil discoveries but share a thought for those parts of the Kingdom Animalia which do not readily fossilise. Invertebrate palaeontologists working on the Annelida (segmented worms and leeches), soft bodied creatures, have very few body fossils to study. As a result, the dedicated scientists which work on them don’t have anything like a complete fossil record of these extremely important creatures.

Trace fossils, such as preserved burrows can help, but the evolutionary history of these ancient animals remains poorly understood.

Cocoon Fossils

In contrast, the distinctive egg cases, often referred to as cocoons of the worms that make up the Class Clitellata, are relatively common in the fossil record. Everything Dinosaur team members have read published papers that explore the fossilised remains of the cocoons from worms that once lived in freshwater environments back in the Triassic. These preserved cocoons provide valuable additional information as to the diversity of micro-faunas within ancient biotas. Unfortunately, little work has been carried out so far on the possibility of using such fossils to establish phylogenetic relationships between families and genera.

Class Clitellata

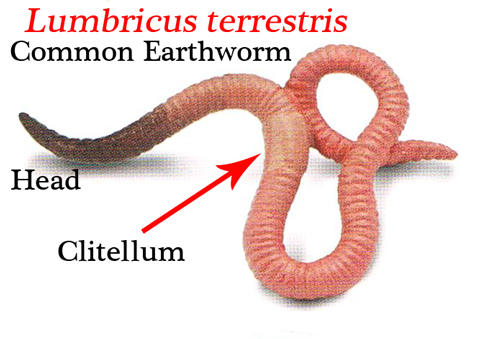

The worms that make up the Class Clitellata are distinguished from other types of segmented worm, in that they have a “collar”. It is this “collar”, called the clitellum that gives this Class its name and it is from the Clitellum that the reproductive cocoon is formed.

A Diagram of a Common Earthworm Showing the Clitellum

Picture credit: Everything Dinosaur

Fossilised Spermatozoa

A team of scientists from the University of Milan, the Swedish Natural History Museum and the Museo de la Plata (Argentina) have published a paper in the academic journal “Biology Letters” that details the discovery of fossilised spermatozoa (sperm) preserved within the secreted wall layers of a fifty-million- year-old clitellate cocoon found in Antarctica. This material represents the oldest fossil animal spermatozoa yet described.

The specimen was collected during a field expedition to the remote Seymour Island, one of a group of small islands at the tip of the Antarctic Peninsula. The Island is extremely significant to palaeontologists as the strata exposed dates from the Late Cretaceous, the Palaeogene and into the early part of the Neogene (Eocene Epoch). Fossils found on Seymour Island include marsupials, proving that in the past terrestrial mammals lived on Antarctica, but the rocks have proved most useful in helping scientists to plot climate change, including the global cooling during the Eocene that led to the glaciation of the Poles.

Fossil is Approximately 50 Million Years Old

Strontium isotope dating gives an age of approximately fifty million years for the fossilised spermatozoa (Ypresian faunal stage of the Eocene), the fossil find was made by chance as a single worm fragment just 0.8 mm wide was studied using a scanning electron microscope. A three-dimensional model was then created using sections of the fragment that had been examined under X-ray microscopy.

A Fragment of the Fossilised Worm Spermatozoa

Picture credit: Swedish Museum of Natural History (Department of Palaeobiology)

When closely examined, the clitellate was found to consist of a solid inner wall, just one fortieth of a millimetre thick. In addition, there was a spongy, outer layer of loosely interwoven cables between 100th and 200th of a millimetre in thickness. The scientists were able to observe images of the microscopic cells embedded in the cocoon wall, including rod-shaped structures with a whip-like tail.

Modestly commenting on the discovery, Benjamin Bomfleur, a palaeobotanist at the Swedish Natural History Museum remarked:

“It was an accidental find. We were analysing the fragments to get a better idea of the structure of the cocoon. When we zoomed into the images, we started noticing these tiny biological structures that look like sperm.”

A Worm Mystery

Working with biologists the team were able to conclude that the fossils resemble the sperm of extant freshwater crayfish worms (Branchiobdellida), although since these worms are only found in the Northern Hemisphere it remains a mystery as to whether or not the Antarctic fossil specimen is closely related. How the fossils came to form in the first place is a little bit of a puzzle too.

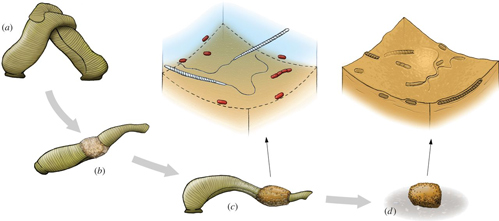

Diagram Illustrating the Inferred Method of Fossilisation of Microorganism (Clitellate Cocoons)

Picture credit: Biology Letters

In the diagram above, the common medicinal leech is used to illustrate a potential theory of how the fossil preservation occurred. Two leeches mate (a), a cocoon is secreted from the clitellum (b), then eggs and sperm are released into the cocoon before the animal retracts and eventually deposits the sealed cocoon on a suitable substrate. Spermatozoa and microbes become encased in the solidifying inner cocoon wall (d).

The scientists anticipate that this accidental discovery will permit systematic surveys of cocoon fossils coupled with advances in non-destructive analytical techniques that will open up new opportunities to explore the evolutionary relationships of minute, soft-bodied animals that are otherwise so rarely found in the fossil record.

Visit Everything Dinosaur’s award-winning website: Everything Dinosaur.