Nosing Around Qianzhousaurus sinensis – The Implications

“Pinocchio rex” Qianzhousaurus sinensis – A new Look for the Tyrannosaurs

Over the last two days or so, there has been a lot of media coverage regarding the discovery of a long-snouted member of the tyrannosaur family, a fearsome, carnivorous dinosaur that has been named Qianzhousaurus sinensis. The fossil discovery is very significant as it establishes the presence of long-snouted tyrannosaurs nestling somewhere amongst the Tyrannosauridae family. Quite where they fit is still up for debate as the phylogeny of this group is becoming more and more complicated as new genera are described. Phylogenetics looks at the evolutionary history of a species or group of organisms, it aims to map out lines of descent and taxonomic relationships.

Qianzhousaurus sinensis

This new tyrannosaur nick-named “Pinocchio rex” due to its long snout, has led to the establishment of a new branch of the tyrannosaur family. Living alongside the bone crushing apex predators that were the deep-skulled tyrannosaurs, there was another closely related group, meat-eaters that probably hunted different sorts of prey and fed in a different way. This new sub-branch or clade of tyrannosaurs has been named the Alioramini (pronounced Al-ee-oh-ram-min-eye), as for the moment it contains just two genera, Alioramus and the newly described Qianzhousaurus.

Alioramus also had a long, narrow snout. The genus name translates as “other evolutionary branch”, as ever since Alioramus was discovered, palaeontologists had suspected that there was a sub-branch of the tyrannosaur family tree. The fossils of Qianzhousaurus go a long way in helping to strengthen this hypothesis.

Long-Snouted Fearsome Tyrannosaur – Qianzhousaurus sinensis

Picture credit: Junchang Lü/Chinese Academy of Geological Sciences

The picture above shows three views of the partial skull and upper jaw of Q. sinensis. The first picture shows a view from the side (lateral), the second picture shows a view looking down onto the fossil (dorsal) and the third picture shows the view from the underside (ventral). The scale bar represents five centimetres.

Scientific Paper Published

In a paper published this week in the journal “Nature Communications”, the authors which include Stephen Brusatte (Chancellor’s Fellow in Vertebrate Palaeontology at the University of Edinburgh) and Junchang Lü (Institute of Geology at the Chinese Academy of Geological Sciences), describe this Theropod as a “remarkable find”. It is indeed, but the story of this fossil’s discovery is also very remarkable.

Back in the late summer of 2010, construction workers helping to build a new industrial park close to the city of Ganzhou in Jiangxi Province (south-eastern China), uncovered the remains of two dinosaurs. One was a small oviraptorid, the second and much more spectacular find represented a substantial meat-eater. The works foreman telephoned a local fossil hunter who visited the site and having examined some of the finds and realised their importance, called in the Ganzhou city Mineral Resources Management Department. A field team was quickly despatched and within a few hours the vast majority of the exposed fossil material was collected, which in the case of the large theropod represented much of the skull and jaws, vertebrae, parts of the pelvis and limb bones.

Late Cretaceous “Hotbed”

Many different types of dinosaur have been found in the sedimentary rocks that are exposed in and around Ganzhou city, it is often described as a “hotbed” for Late Cretaceous dinosaur discoveries. The field team had to work fast, as a number of fossil dealers had also heard of the discovery and if they had got to the bones first, then the fossilised remains could have ended up being sold on the black market.

As things turned out, following the speedy collection, the story of Qianzhousaurus slowed down to a snail’s pace. The fossils which had been bagged up remained with the Mineral Resources Management Department for the best part of eight months, before they were presented to the Ganzhou Natural History Museum. In August 2012, the museum assembled a team of Chinese scientists and technicians to examine the bones and begin the reconstruction of the specimen.

Close Phylogenetic Relationship with Alioramus

The initial research work was concluded in January of last year and the full significance of the discovery was realised. Here was an adult tyrannosaur that exhibited skull characteristics that placed it in a close phylogenetic relationship with the tyrannosaur known as Alioramus. This was proof that the long suspected sub-branch of long-snouted tyrannosaurs had existed.

Further work was undertaken and the formal academic paper published this week. Say hello to Qianzhousaurus sinensis. Qianzhousaurus is pronounced Chy-an-shoe-sore-us, the genus name is derived from the old name for the city of Ganzhou (Qianzhou), the species name reflects that this dinosaur was Chinese.

An Illustration of the Late Cretaceous Tyrannosaur Q. sinensis

Picture credit: Chuang Zhao

This dinosaur had a number of small horns or bumps running along its snout. It is illustrated attacking a feathered oviraptorid dinosaur, as the fossils of Qianzhousaurus sinensis were found in association with the bones of a small member of the Oviraptoridae family.

Dr Brusatte explained:

“This is a different breed of tyrannosaur. It has the familiar toothy grin of T. rex, but its snout was much longer and it had a row of horns on its nose. It might have looked a little comical, but it would have been as deadly as any other tyrannosaur, and maybe even a little faster and stealthier.”

This specimen is very significant as the fused skull bones identify it as an adult animal. Qianzhousaurus probably weighed around 1,000 kilogrammes and reached lengths of around 8-9 metres. Smaller than its deep-skulled tyrannosaur contemporaries, Qianzhousaurus probably occupied a niche in the Late Cretaceous food chain, that of a secondary predator. Even if it lived in packs, it probably did not specialise in hunting really large herbivorous dinosaurs. It was nowhere near as powerful as some of the other Upper Cretaceous tyrannosaurs known from Asia, the likes of Tarbosaurus and the recently described Zhuchengtyrannus.

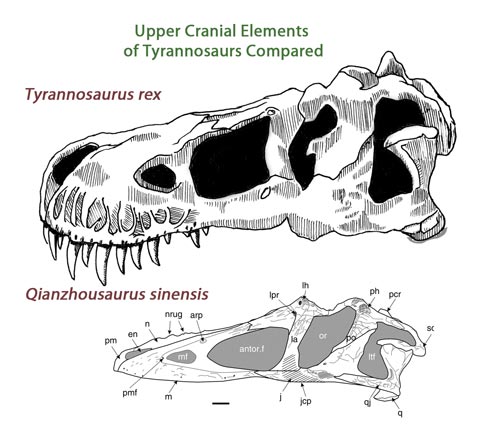

Tyrannosaur Skull Comparisons (T. rex versus Q. sinensis)

Picture credit: Journal of Nature Communications and Everything Dinosaur

To read an article about Zhuchengtyrannus: New Species of Asian Tyrannosaur Announced.

Studying Tyrannosaurs

The bite force that this predator could generate was nowhere near the bone crushing bite force of Tyrannosaurus rex. This was a more graceful, agile hunter, perhaps stalking feathered dinosaurs and other reptiles. Consider Qianzhousaurus as the leopard that shares the same habitat as a lion.

For models and replicas of Qianzhousaurus, numerous tyrannosaurs and other prehistoric animals: PNSO Age of Dinosaurs Models.

This fossil is very important for a number of reasons, firstly there is a substantial amount of fossil material to study, scientists can learn more about the tyrannosaur family as a result. Secondly, unlike the two known Alioramus specimens which both represent juveniles, this adult animal demonstrates that there were long-snouted forms of Tyrannosauridae. A sub-branch of tyrannosaurs did exist and the presence of a long-snout in the likes of the Alioramus specimens cannot be attributed to the fact that these not fully grown dinosaur specimens “hadn’t filled out yet” as a colleague puts it.

Thirdly and perhaps most crucially of all, this fossil discovery from south-eastern China was found in Upper Cretaceous deposits located more than two thousand kilometres away from the Upper Cretaceous deposits that yielded the Alioramus material. It seems that the long-snouted tyrannosaurs were widely distributed in Asia during the last few million years of the Cretaceous period. This means that there are, very probably a number of other “Pinocchio rex” tyrannosaurs awaiting discovery.

We wonder what Geppetto would have made of it all…