Digitally Reconstructing a Famous Dinosaur Trackway

Dinosaur Tracks Lost to Science for Decades Recreated Using Digital Technology

A set of dinosaur tracks, one from a large sauropod dinosaur, the second set from a meat-eating dinosaur, have been digitally recreated permitting scientists to study the complete tracks for the first time in more than seventy years. The footprints, which cover a distance of approximately forty-five metres, are part of a number of dinosaur trackways preserved in near marine sediments that were laid down between 113 and 110 million years ago (Cretaceous geological period). The theropod dinosaur’s three-toed prints overlie the larger sauropod prints and this indicates that the large herbivorous dinosaur passed first, perhaps the carnivore was stalking the sauropod.

“Dinosaur Chase Tracks”

The tracks, now forming part of the bed of the Paluxy River in Texas are often referred to as the “dinosaur chase tracks”, although scientists cannot be certain whether or not the theropod was stalking its prey.

The Famous Dinosaur “Chase” Tracks (Paluxy River, Texas)

Picture credit: Everything Dinosaur from original artwork by John Sibbick

The picture above shows a potential interpretation of the Paluxy River tracks, with the huge, plant-eating dinosaur being stalked by the bipedal, theropod dinosaur. It is difficult to assign a genus to these dinosaur footprints, but it has been speculated that the theropod may have been a member of the Acrocanthosaurus genus, as fossils of this large predator have been found in similar aged rocks and a dinosaur bone from the Glen Rose Formation, has been assigned to Acrocanthosaurus.

Famous Dinosaur Trackway

Using a technique called photogrammetry, scanning and combining photographs taken during research at the location back in the 1940s, the scientists were able to build a digital model of the site. The computer model created is the only complete record available to study as some of the physical tracks themselves have been lost.

The Paluxy River dinosaur tracksite is among the most famous in the world. In 1940, Dr Roland T. Bird, a American palaeontologist from the American Museum of Natural History (New York), described and excavated a portion of the site containing associated theropod and sauropod trackways, the so-called “dinosaur chase tracks”. As the river flow was in danger of completely eroding away the dinosaur footprints, it was decided to remove the tracks in a serious of carefully excavated blocks.

The trackway was thus broken up into a number of sections. Split up as it was, the fossil specimens were housed in different museum collections and over the years the slabs have deteriorated and a portion of the track has been lost.

International Research Team

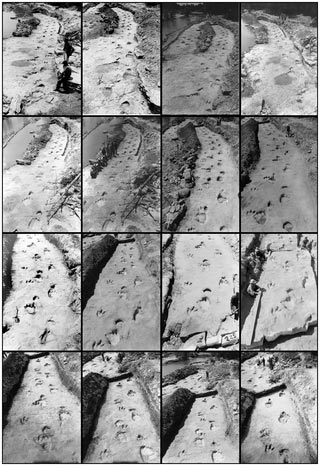

The research team, which included scientists from Liverpool University, the Royal Veterinary College (London) and Indiana-Purdue University, Indiana, applied state-of-the-art photogrammetric techniques to seventeen black and white photographs of the tracks that had been taken by Dr Bird during the 1940 trace fossil study. By producing highly detailed scans of the original photographs and their corresponding negatives the researchers were able to digitally reconstruct the site prior to its fateful excavation.

Furthermore, the three-dimensional study was able to corroborate sketches drawn by Dr Bird when the trackway was first scientifically described.

Sixteen of the Photographs from the 1940 Expedition Used to make the 3-D Digital Map

Picture credit: PLOS One

This new mapping technique demonstrates the exciting potential for digitally recreating palaeontological, geological, or archaeological specimens that have been lost to science, but for which photographic documentation still exists.

Dinosaur Footprints

Using dinosaur footprints made back in the Aptian/Albian faunal stage of the Cretaceous, this work has dramatically illustrated the potential for the technique of historical photogrammetry, permitting the creation of highly detailed and precise 3-D maps of sites that may have been physically lost and just preserved in photographs. In this instance, the last time the set of dinosaur tracks was complete was back in 1940 prior to the removal of the footprint blocks.

Commenting on the significance of this study, lead researcher Dr Peter Falkingham (Royal Veterinary College) stated:

“Here we’re showing that you can do this to lost or damaged specimens or even entire sites if you have photographs taken at the time. That means we can reconstruct digitally, and 3-D print, objects that no longer exist.”