Research Suggests Marine Crocodiles Were Very Different from Todays

Scientists at the University of Edinburgh have concluded that Late Jurassic marine crocodiles may have fed more like Killer Whales than extant crocodiles and one genus could have sucked prey into its mouth or simply attacked and torn other large marine creatures apart with its strong jaws and teeth.

Marine Crocodile Research

Marine crocodiles (crocodylomorphs) represent a branch of the crocodile family tree that radiated out from land base forms during the Mesozoic and evolved into a variety of families and genera. There is an extensive fossil record with numerous skulls and other fossilised bones as well a large numbers of individual teeth for palaeontologists to study.

Marine crocodiles shared similar characteristics, unlike their land-based ancestors these reptiles adapted to a nektonic (actively swimming) life by slowly losing their body armour (scutes/osteoderms) and becoming more streamlined. Their limbs evolved into paddles and most species had broad tails which ended in a hypocercal tail fin. A hypocercal tail fin is a fin which is not symmetrical along the horizontal axis in line with the caudal vertebrae (in the case of vertebrates). The lower tail lobe is enlarged and bigger than the upper tail lobe. It is very likely that these crocodiles propelled themselves through the water in the same way that crocodiles do today. The tail was the source of propulsion, the limbs (paddles) may have been used to make changes in direction and small adjustments in the water column. However, these evolutionary adaptations made these creatures much more efficient swimmers than land based crocodylomorphs.

An Illustration of a Typical Marine Crocodile

The picture (above) shows the package art for the PNSO Dakosaurus replica.

To view the PNSO range of prehistoric animals including marine reptiles: PNSO Marine Crocodiles and Prehistoric Animal Models.

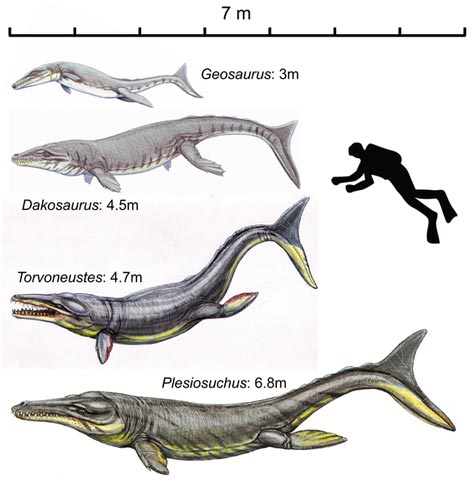

One super-family of the marine crocodiles, the Metriorhynchidae seems to have had a particularly large geographical distribution, with fossils being found in England, France, Switzerland, Italy and Germany as well as the Americas including Chile and Argentina. As a group, these carnivorous reptiles seemed to have their heyday in the Late Jurassic but fewer fossils have been found in Lower Cretaceous strata. The research team, led by Dr Mark Young of the School of Geosciences (University of Edinburgh) studied two types of marine crocodile Dakosaurus and the larger Plesiosuchus. They have concluded that these large, contemporaneous predators probably predated on different types of prey.

To read about the discovery of Jurassic crocodile fossils in Switzerland: Marine Crocodile Fossils Found in the Land of Chocolate, Pen Knives and Cuckoo Clocks.

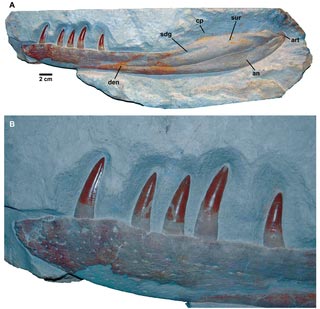

Dakosaurus

Dakosaurus spp. grew to lengths approaching five metres, they were not the largest types of marine crocodile but they did have the most robust lower jaws and in proportion to their body size, much larger teeth. The teeth of Dakosaurus spp were designed for slicing, the Edinburgh researchers conclude that this type of marine crocodile evolved a specialism for tackling large prey. The teeth and strong jaws being capable of dismembering large-bodied prey and crushing bones. In addition, the research team have concluded that one species of Dakosaurus (Dakosaurus maximus) may have been capable of creating a pressure differential inside its strong jaws that permitted it to suck in prey. Many of the teeth found in the fossilised jaws of Dakosaurus are broken and show extensive wear. The scientists have concluded that these pathologies are indicative of the tougher, larger body parts that these animals were consuming. Teeth may also have been broken as these crocodylomorphs tore their victims apart.

The Lower Jaw of a Dakosaurus (Dakosaurus maximus)

Picture credit: PLoS One

The Plesiosuchus genera also had strong jaws, large fenestrae (openings in the skull) would have anchored strong muscles to give these crocodiles a powerful bite. They could also gape their jaws very wide enabling them to tackle large prey items, but probably animals no bigger than their mouths could gape. The teeth of Plesiosuchus spp. are proportionally smaller and more conical than the teeth of Dakosaurus. Fossilised teeth ascribed to Plesiosuchus lack the crown breakage seen with Dakosaurus teeth. This suggests that Plesiosuchus did not eat the same animals as the smaller Dakosaurus. They may have killed their victims with a single bite before swallowing their meal whole.

The relationship between Dakosaurus and Plesiosuchus is very similar to that seen with North Atlantic Killer Whales today. There is a larger type of Killer Whale that lacks broken teeth, whilst there is a smaller type of Killer Whale that tends to have extensive crown breakage. Marine biologists have proposed that these differences in teeth wear are associated with diet. Each type of Killer Whale specialising in different types of prey. Plesiosuchus may have been a specialist piscivore (fish-eater) tackling prey no more than a metre in length perhaps, whereas Dakosaurus may have hunted ichthyosaurs, other marine reptiles and larger types of fish.

Size Comparisons between Different Types of Marine Crocodile

Picture credit: PLoS One

Different Types of Feeding Behaviour

The research team have concluded that this different feeding behaviour helps to explain why so many apex predators were able to live together in the Late Jurassic marine environments.

Commenting on the research, one of the authors of the scientific paper that has been published on this subject, Dr Lorna Steel stated:

“The skull and tooth morphology show that they all ate different prey, and fed in different ways.”

Leave A Comment