How Snakes Lost Their Legs

Serendipity can play a huge role in science, for Dr Dave Martill a chance encounter with a 115-million-year-old fossil whilst taking a group of third year students around a German museum, has led to a breakthrough in our understanding of how snakes evolved. A beautifully preserved fossil snake with four limbs, the first snake fossil with four legs ever found, making this specimen a transitional form between limbed lizards and the snakes we know today, is helping scientists to piece together the puzzle of how snakes lost their legs.

Fossil Snake

Over the last fifteen years or so the University of Portsmouth has arranged a tour of German natural history museums for their third year vertebrate palaeontology students. On a visit to one such museum, the famous Bürgermeister-Müller-Museum in Solnhofen (Southern Germany), to view the spectacular Jurassic limestone fossils including Archaeopteryx, by chance, the Museum was hosting an exhibit of much younger Cretaceous fossils from Brazil.

Dr Martill, took his students around the exhibit and to his amazement he spotted on display a small, exquisitely preserved fossil of a snake, but this snake had tiny legs. Enquiries were made and Dr Martill working with Dr Helmut Tischlinger (Bürgermeister-Müller-Museum) and Dr Nicholas Longrich (University of Bath), have published today in the academic journal “Science” a description of this unique fossil specimen.

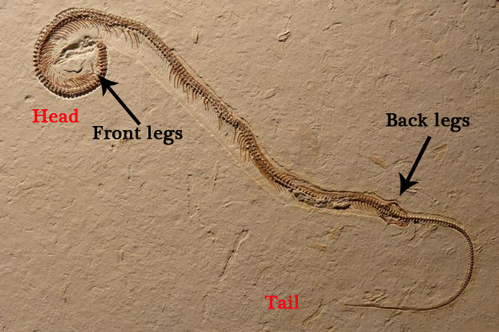

The Four-Legged Snake Fossil

Picture credit: Dr Dave Martill/University of Portsmouth with additional annotation by Everything Dinosaur

Tetrapodophis amplectus

This new snake species has been named Tetrapodophis amplectus (pronounced Tet-tra-poe-doh-fis am-pleck-tus), and it means “four-legged embracing snake”, the embracing element as the limbs were too small to be used in locomotion, they may well have served a function in holding prey or embracing mates.

Both the slab and counter slab are known but their exact provenance remains a mystery. The fossil specimens were collected many decades ago and held in a private collection. The fine-grained limestone matrix is dotted with occasional coprolites from an ancient fish called Dastilbe, bedding plains associated with these coprolites come from the Nova Olinda Member of the Crato Formation found in north-eastern Brazil.

Early Cretaceous Fossil

The exact age of this Formation is contentious, the lack of marine zonal fossils make dating extremely difficult, but scientists estimate that this important, highly fossiliferous strata dates from between 126 to 113 million years ago (Aptian to Early Albian faunal stages).

The snake measures around twenty centimetres in length and it was very probably a juvenile. Just how big this snake could grow to remains unknown. The fossil is preserved in almost complete articulation indicating a low energy fossil preservation environment and a lack of disturbance by scavengers. This little snake ended up in a hypersaline salt lake and this is what aided its fantastic preservation.

An Illustration of the Early Snake Tetrapodophis (T. amplectus) with Prey

Picture credit: Julius Csotonyi

Last Meal Preserved

Evidence of the snake’s last meal was also preserved, however, it was not a small mammal as depicted in the excellent illustration by renowned palaeoartist Julius Csotonyi. Dr Tischlinger, is an expert in the use of UV light to help expose hidden details of fossil specimens, a technique he has used to great effect on the finely-grained, lithographic limestone specimens of Solnhofen. When viewed under ultraviolet light, the fossil revealed the remains of a small vertebrate, most probably a salamander.

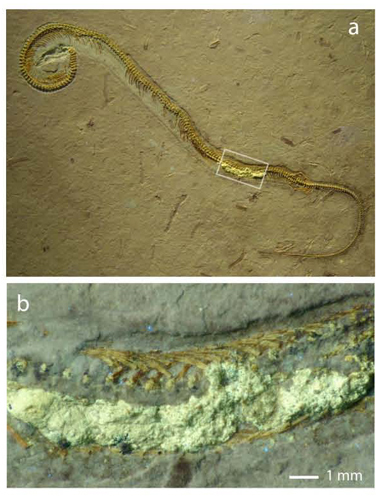

Abdomen Viewed under Ultraviolet Light Reveals Gut Contents

Picture credit: Journal Science

The photograph above shows the position of the gut contents (fluorescing white) – (a) and (b) phosphatised gut contents (also fluorescing white) with tiny fragments of bone (orange).

Snakes Evolved from Lizards

It is generally accepted that snakes evolved from lizards at some point in the distant past.

Commenting on the significance of this fossil Dr Martill stated:

“What scientists don’t know yet is when they evolved, why they evolved and what type of lizard they evolved from. This fossil answers some very important questions, for example it now seems clear to us that snakes evolved from burrowing lizards, not from marine lizards.”

Dr Longrich who has extensively studied the evolution of snakes, commented:

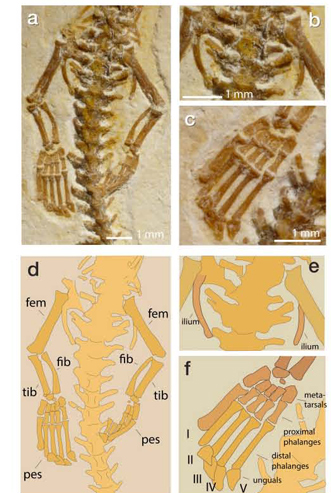

“It is a perfect little snake, except it has these little arms and legs, and they have these strange long fingers and toes. The hands and feet are very specialised for grasping. So when snakes stopped walking and started slithering, the legs didn’t just become useless little vestiges – they started using them for something else. We’re not entirely sure what that would be, but they may have been used for grasping prey, or perhaps mates.”

Fossil Snake – Limbs for Holding not for Walking

At just 4 mm and 7 mm long respectively, the tiny hands and feet were not aiding locomotion, but the well-defined claws suggest that they might have helped Tetrapodophis grasp and hold prey. They may also have served a role as “claspers” in mating.

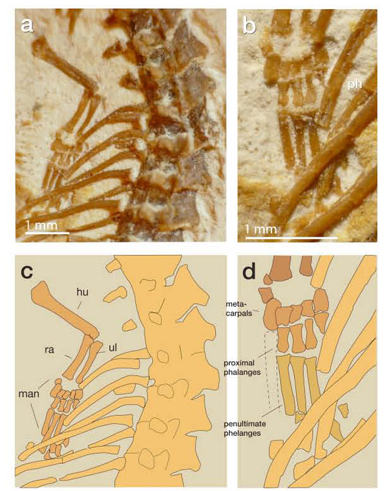

A Close Up of the Left Forelimb (Tetrapodophis amplectus)

Picture credit: Science Journal

The photographs and illustrations above show the T. amplectus holotype (BMMS BK 2-2), specifically a close up view of the left forelimb and hand (manus). Photograph (a) shows the forelimb, whilst (b) is a close up view of the manus (scale bar 1 mm). Illustrations (c) and (d) show the layout of the bones, the dotted line in (d) indicates a missing bone.

Key

- hu – humerus

- man – manus

- ra – radius

- ul – ulna

A Close Up of the Hindlimbs (Ventral View – Looking from Underneath)

Picture credit: Science Journal

The Arrangement of the Hindlimbs

The pictures and diagrams above show the arrangement of the hindlimbs (ventral view), as seen from underneath the body. Photograph (a) shows the hindlimbs, (d) an illustration of the hindlimbs, (b) is a close up of sacrum and pelvic area, illustrated by diagram (e). Photograph (c) shows the delicate hind foot which measures approximately 7 mm long. Diagram (f) shows a layout of the bones in the foot.

Key

- fem – femur

- fib – fibula

- tib – tibia

The fossil suggests that snakes may have lost their limbs to help them burrow, either through sediment of through leaf litter, speculated a member of the Everything Dinosaur team. Cladistic analysis places the origin of the snakes close to the Iguana and the Anguimorpha families, (the Anguidae family includes limbless lizards such as slow worms), although the exact phylogenetic relationship remains disputed. The discovery of this fossil suggests that the snake family, a very widespread and diverse group of reptiles today, probably first evolved on the southern super-continent of Gondwana.