Palaeontologists Name New Species of Ottoia Worm – Burgess Shale Creatures

Whilst many a television documentary or published article on the fauna of the Burgess Shale focuses on the nektonic predators (actively swimming creatures above the sea floor), such as the formidable Anomalocaris, lurking in the soft mud of the sea floor itself was another very nasty hunter, one that left an extremely rich fossil record. The most abundant type of creature preserved in the Burgess Shale is a type of worm, a member of the Phylum Priapulidae and now thanks to a detailed study of the teeth, hooks and spines on this tubular predator, scientists have discovered a method of identifying new species and also of determining just how abundant these creatures actually may have been.

An Ottoia Fossil (Burgess Shale)

Burgess Shale Creatures

Ottoia fossils from the Burgess Shale of British Columbia (Canada), measure just a few centimetres in length and they are one of the few types of creature preserved in those 505 million year old sediments that can be associated with a living animal group, the entirely marine priapulids. At least fifteen hundred specimens have been excavated from the Burgess Shale deposits. These creatures may have lived in “U” shaped burrows and ambushed other creatures that wandered or swam to close to the burrow’s entrance. It could grab food with a proboscis, an extendible mouth which was equipped with tiny hooks and lined with teeth and spines.

The team of scientists from Cambridge University and the University of Leicester, writing in the on line Journal “Palaeontology” used a variety of techniques to examine micro-fossils to identify different types of teeth from Ottoia It is from this analysis that the team discovered that the most common type of priapulid associated with the Burgess Shale, Ottoia prolifica, actually represented two species.

Prehistoric Worms

As a result of this research, a new species of Ottoia worm has been identified in the Burgess Shale deposits – Ottoia tricuspida. O. tricuspida has been so named as it has distinctive, three-pronged teeth. Using various microscopy techniques to examine the tiny teeth recovered from drill cores and from other samples, the scientists propose that subtle variations in the teeth could help to identify more species in Cambrian biota and in addition, as the teeth are more likely to be preserved than the soft bodies of these creatures, the teeth could help to establish how widespread such worms were in the Cambrian geological period.

The Ottoia Genus

Ottoia prolifica was named by Charles Doolittle Walcott in 1911. Walcott, an American invertebrate palaeontologist, discovered the Burgess Shale deposits in the Canadian Rockies back in 1909. These bands of mudstone and shale are very rich in fossils. The frequency of Ottoia fossil material might not be anything to do with the abundance of these types of animals in the biota, the numbers found could reflect the fact that these animals lived in soft sediment. If one of these worms died in their burrow, then they could set in motion the fossilisation process. The soft mud would act as an excellent medium to promote the preservation of creatures that lived in the sediment.

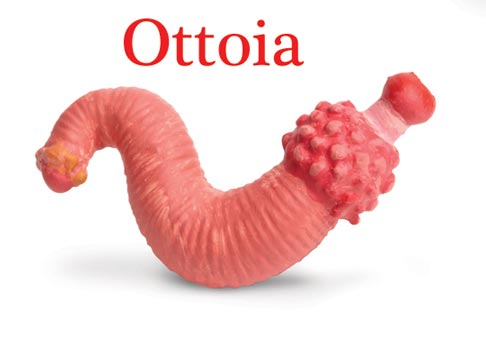

A Model of Ottoia (Safari Ltd Cambrian Life Toob)

Safari Ltd have a wonderful model of Ottoia in the Cambrian Life Toob. This Toob contains a set of eight prehistoric animals that represent the bizarre fauna of the Cambrian explosion.

To view this Toob and other prehistoric animal model sets: Wild Safari Prehistoric World Models.

A Teeth, Hooks and Spines Associated with Ottoia spp.

Picture credit: Palaeontology Journal

Leave A Comment