Fossil finds, new dinosaur discoveries, news and views from the world of palaeontology and other Earth sciences.

New Research Suggests Rapid Neck Evolution in Plesiosaurs

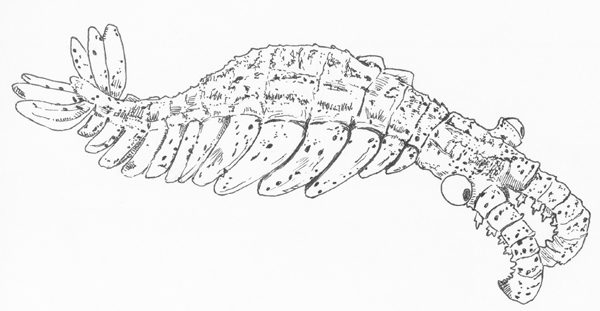

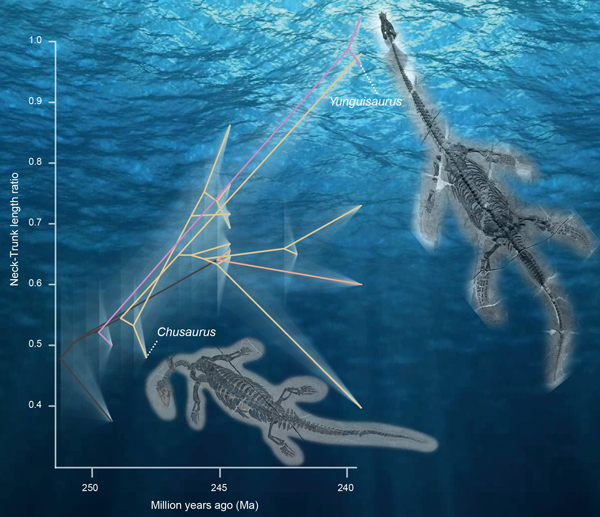

Long necks in proportion to overall body length is known in many tetrapods. Giraffes and sauropods are typical examples. The evolution of a longer neck being linked to feeding strategies. A newly described ancestor of plesiosaurs named Chusaurus xiangensis suggests that neck elongation occurred rapidly in these types of marine reptiles. Lengthy necks, ideal for pursuing fast-moving nektonic prey such as fish and squid developed quickly over a five-million-year period approximately 250 million years ago.

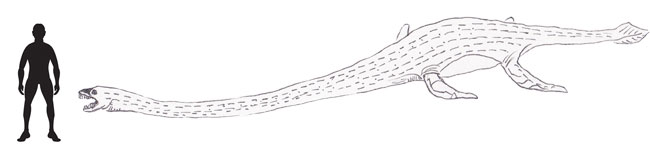

Picture credit: Qi-Ling Liu

Chusaurus xiangensis

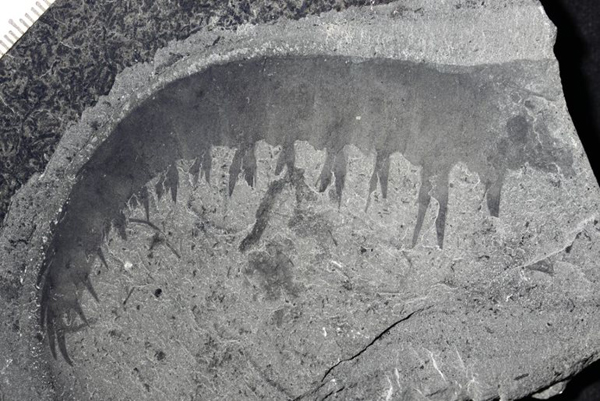

Researchers have reported a new species of pachypleurosaurid sauropterygian from southern China. The new species shows key features of its Middle Triassic relatives, but has a relatively short neck, measuring 0.48 of the trunk length, compared to > 0.8 from the Middle Triassic onwards. Comparative phylogenetic analysis shows that neck elongation occurred rapidly in all Triassic eosauropterygian lineages. This evolution was probably driven by feeding pressure in a time of rapid re-establishment of new kinds of marine ecosystems.

The lengthy necks of marine reptiles, used for chasing fast-moving fishes, developed quickly over a five-million-year period around 250 million years ago.

Adding More Vertebrae

The researchers conclude that pachycephalosaurs lengthened their necks mainly by adding new vertebrae.

The findings, published today in BMC Ecology and Evolution, and carried out by scientists in China and the UK, show that pachypleurosaur taxa lengthened their necks mainly by adding new vertebrae. One taxon, Keichousaurus had more than 20 cervical vertebrae, while some Late Cretaceous plesiosaurs such as Elasmosaurus had as many as 72. Its neck was five times the length of its trunk.

Picture credit: Everything Dinosaur

The illustration (above) was inspired by the recently introduced CollectA Age of Dinosaurs Elasmosaurus figure.

To view this range of prehistoric animal figures: CollectA Age of Dinosaurs Prehistoric Life Models.

Pachypleurosaurs Like Chusaurus xiangensis Evolved in the Early Triassic

These reptiles originated in the Early Triassic, four million years after the end-Permian mass extinction that wiped out around 90% of Earth’s species. Ecosystems were undergoing dramatic changes in the aftermath of the extinction event.

The authors of the study, including scientists from the University of Bristol, studied the Chusaurus xiangensis fossils from Hubei Province (China). Its neck had begun to lengthen. However, it was less than half the length of its trunk, compared to later relatives that had a neck length to trunk ratio of greater than 0.8 (80%).

Two Fossil Skeletons to Study

Lead researcher Qi-Ling Liu from the China University of Geosciences (Wuhan), commented:

“We were lucky enough to find two complete skeletons of this new beast. It’s small, less than half a metre long, but this was close to the ancestry of the important group of marine reptiles called Sauropterygia. Our new reptile, Chusaurus, is a pachycephalosaur, one of a group of small marine predators that were very important in the Triassic. I wasn’t sure at first whether it was a pachypleurosaur though because the neck seemed to be too short.”

Co-author Dr Li Tian (China University of Geosciences) added:

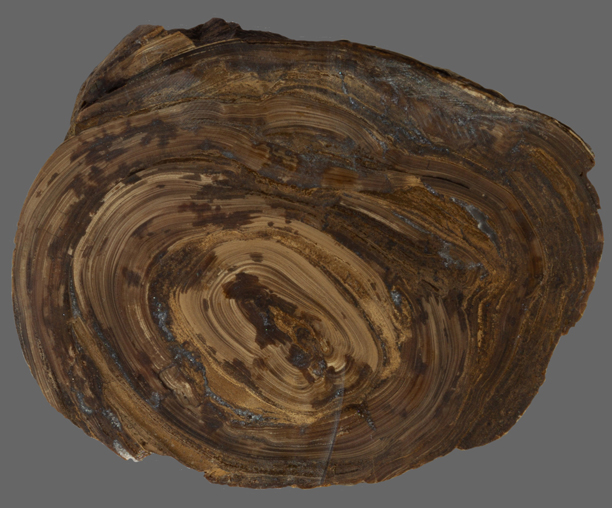

“The fossils come from the Nanzhang-Yuan’an Fauna of Hubei. This has been very heavily studied in recent years as one of the oldest assemblages of marine reptiles from the Triassic. We have good quality radiometric dates showing the fauna is dated at 248 million years ago.”

Fellow author Professor Michael Benton of the University of Bristol’s School of Earth Sciences explained:

“The end-Permian mass extinction had been the biggest mass extinction of all time and only one in twenty species survived. The Early Triassic was a time of recovery and marine reptiles evolved very fast at that time, most of them predators on the shrimps, fishes and other sea creatures. They had originated right after the extinction, so we know their rates of change were extremely rapid in the new world after the crisis.”

Not All Vertebrates Evolve in the Same Way

Not all vertebrates evolve in the same way. When it comes to evolving a lengthy neck, giraffes have changed in a different way to pachypleurosaurs. Most mammals have seven neck vertebrae. Giraffes have seven neck bones too. Each one is extremely long, so these herbivores can browse on the tops of trees. Chusaurus had seventeen. Later pachycephalosaurs had twenty-five. Late Cretaceous plesiosaurs such as the huge Elasmosaurus had seventy-two. These long necks with numerous vertebrae are likely to have been extremely flexible. These marine reptiles could whip their necks round and grab a fish, whilst keeping their body steady.

Flamingos also have long necks so they can reach the water to feed. They have extra cervical vertebrae, up to twenty, but each one is also long.

Chusaurus xiangensis – Perfectly Adapted to its Environment

Dr Benjamin Moon, who also collaborated in this study stated:

“Our study shows that pachycephalosaurs doubled the lengths of their necks in five million years, and the rate of increase then slowed down. They had presumably reached some kind of perfect neck length for their mode of life.”

Dr Moon added:

“We think, as small predators, they were probably mainly feeding on shrimps and small fish, so their ability to sneak up on a small shoal, and then hover in the water, darting their head after the fast-swimming prey was a great survival tool. But there might have been additional costs in having a much longer neck, so it stabilised at a length just equal to the length of the trunk.”

Everything Dinosaur acknowledges the assistance of a media release from the University of Bristol in the compilation of this article.

The scientific paper: “Rapid neck elongation in Sauropterygia (Reptilia: Diapsida) revealed by a new basal pachypleurosaur from the Lower Triassic of China” by Qi-Ling Liu, Long Cheng, Thomas L. Stubbs, Benjamin C. Moon, Michael J. Benton, and Li Tian published in BMC Ecology and Evolution.

Visit the award-winning Everything Dinosaur website: Everything Dinosaur.