The Earliest Paranthropus robustus Skull

The discovery of a near complete skull of the hominin Paranthropus robustus has shed new light on the evolution of this enigmatic species, related to but not likely to be a direct ancestor of the hominin lineage that led to the evolution of our own species. The fossil was found at the world famous Drimolen Main Quarry (DMQ) site, some twenty-five miles north of Johannesburg, South Africa. This site consists of in-fill deposits from an ancient cave system and it has produced a number of remarkable fossil specimens of early hominins that co-existed around two million years ago.

Paranthropus robustus

The specimen (DNH 155), is believed to represent the skull of a large, adult male and the fossil has been dated from approximately 2.04–1.95 million years ago (Gelasian age of the early Pleistocene), it is the earliest known Paranthropus skull discovered to date.

Specimen Number DNH 155 The Skull of Paranthropus robustus

Picture credit: Andy Herries, La Trobe Archaeology

Discovered on Father’s Day

Field team members from La Trobe University’s Archaeology Department (Melbourne, Australia), led the excavation work. The rare skull fossil was discovered in 2018, on June 20th, appropriately Father’s Day in South Africa. During the careful excavation, cleaning and preparation of the fossil, the specimen was nicknamed the “Father’s Day fossil”.

The skull was found close to the location of Homo erectus skull material, that at around two million years of age, provided strong evidence to support the hypothesis that H. erectus evolved in Africa rather than in Asia. Lead author of the paper outlining the discovery of the partial H. erectus skull was Professor Andy Herries (La Trobe University), the Director of the Australian Research Council-funded Drimolen project, who also co-authored the scientific paper on DNH 155 that was published this week in the journal Nature Ecology & Evolution.

To read more about the Homo erectus discovery at the Drimolen Main Quarry site: Homo erectus Originated in Southern Africa.

The Drimolen Main Quarry – A Hugely Significant Location for Early Hominin Fossil Material

Picture credit: Andy Herries, La Trobe Archaeology

Describing Paranthropus robustus

Although, small in stature compared to modern humans, these early hominins were strongly built, small-brained and they possessed particularly robust jaws and large teeth. Adaptations for a mainly vegetarian diet consisting of roots and tubers. Paranthropus robustus co-existed with other direct human ancestors and is regarded as a “cousin species” to the hominin lineage that led to Homo sapiens. The researchers postulate that the DNH 155 specimen provides the first high resolution evidence for microevolution within an early hominin species.

The most complete P. robustus skull (DNH 7), which was found at the DMQ site in 1994, differs from other P. robustus skull material found at other chronologically younger locations. These differences had been put down to sexual dimorphism, with DNH 7 believed to represent the skull of a female. This led palaeoanthropologists to speculate that if there was sexual dimorphism within the Paranthropus genus then these hominins could have lived in social groups like extant gorillas, with a large dominant male looking after a number of females and their offspring.

Examining the Skulls

However, the newly described DNH 155 skull shares a number of characteristics with the contemporaneous DNH 7 skull.

Co-lead author Jesse Martin (La Trobe University), explained the significance of DNH 155 stating that it could lead to a revised system for classifying and understanding the palaeobiology of human ancestors.

The PhD student commented:

“Demonstrating that Paranthropus robustus is not especially sexually dimorphic removes much of the impetus for supposing that they lived in social structures similar to gorillas, with large dominant males living in a group of smaller females. The DNH 155 male fossil from Drimolen is most similar to female specimens from the same site, whereas Paranthropus robustus specimens from other sites are appreciably different.”

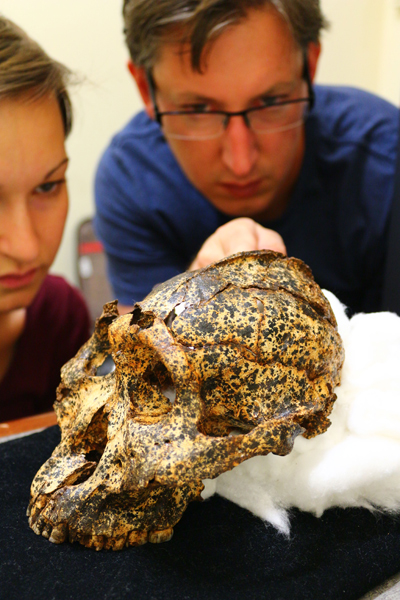

PhD Student Jesse Martin and Co-author Dr Angeline Leece Examine the Skull

Picture credit: Andy Herries, La Trobe Archaeology

A Rare Example of Microevolution within Hominins

Mr Martin said the discovery is a rare example of microevolution within a human lineage, showing that Paranthropus robustus evolved their powerful jaws and strong teeth, adaptations that evolved incrementally, possibly over hundreds of thousands of years in response to environmental change.

Mr Martin added:

“The Drimolen fossils represent the earliest known, very first step in the long evolutionary story of Paranthropus robustus.”

Professor Andy Herries elucidated:

“The DNH 155 cranium shows the beginning of a very successful lineage that existed in South Africa for a million years. Like all other creatures on Earth, to remain successful our ancestors adapted and evolved in accordance with the landscape and environment around them. For the first time in South Africa, we have the dating resolution and morphological evidence that allows us to see such changes in an ancient hominin lineage through a short window of time.

“We believe these changes took place during a time when South Africa was drying out, leading to the extinction of a number of contemporaneous mammal species. It is likely that climate change produced environmental stressors that drove evolution within Paranthropus robustus.”

Staring at the Face of DNH 155 (Male P. robustus)

Picture credit: Andy Herries, La Trobe Archaeology

Paranthropus robustus Co-existed with Homo erectus

Co-lead author, La Trobe’s Dr Angeline Leece, said it was important to know that Paranthropus robustus appeared at roughly the same time as our direct ancestor Homo erectus, as demonstrated by the H. erectus fossil material representing the skull of a child found within a few metres of DNH 155.

Dr Leece commented:

“These two vastly different species, Homo erectus with their relatively large brains and small teeth, and Paranthropus robustus with their relatively large teeth and small brains, represent divergent evolutionary experiments. Through time, Paranthropus robustus likely evolved to generate and withstand higher forces produced during biting and chewing food that was hard or mechanically challenging to process with their jaws and teeth – such as tubers. Future research will clarify whether environmental changes placed populations under dietary stress and how that impacted human evolution.”

As Dr Leece pointed out, whilst the lineage made up of our direct ancestors survived this period of environmental change and the Paranthropus genus is extinct having left no direct descendants, the fossil record indicates that two million years ago, Paranthropus robustus was much more common than Homo erectus. The Drimolen project is likely to continue to play a key role in helping us to understand the evolutionary history of our own species and the fates of those other hominins that ultimately became extinct.

Important Implications for Interpreting the Human Fossil Record

Co-author Professor David Strait (Department of Anthropology, Washington University in St. Louis USA), stated the DNH 155 skull fossil had important implications for interpreting diversity in the fossil record of hominins.

He explained:

“We think that palaeoanthropology needs to be a bit more critical about interpreting variation in anatomy as evidence of the presence of multiple species. Depending on the ages of fossil samples, differences in bony anatomy might represent changes within lineages rather than evidence of multiple species.”

Everything Dinosaur acknowledges the assistance of a media release from La Trobe University in the compilation of this article.

The scientific paper: “Drimolen cranium DNH 155 documents microevolution in an early hominin species” by Jesse M. Martin, A. B. Leece, Simon Neubauer, Stephanie E. Baker, Carrie S. Mongle, Giovanni Boschian, Gary T. Schwartz, Amanda L. Smith, Justin A. Ledogar, David S. Strait and Andy I. R. Herries published in Nature Ecology & Evolution.

The Everything Dinosaur website: Prehistoric Animal Models and Dinosaur Toys.

Leave A Comment