Explosive Radiation of Bird Species After Dinosaur Demise

Birds Evolved Very Rapidly after Cretaceous Mass Extinction

The discovery of the fragmentary remains of a tiny bird is helping scientists to piece together the evolution of modern types of bird. It seems that the Aves (birds), were very quick off the mark after the demise of the dinosaurs and the flying reptiles at the end of the Cretaceous*, within a few million years of the extinction event, the ancestors of most types of today’s birds had evolved.

Palaeontologists had been aware of the rapid evolution and radiation of the Mammalia after the end Cretaceous extinction event, but the birds too underwent a speedy period of evolution to exploit the environmental niches vacated by extinct organisms. Writing in the Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences – USA (PNAS), researchers describe the discovery of a new species of fossil bird from New Mexico. As the oldest known tree-dwelling bird species amongst modern bird groups, the fossils of this nuthatch-sized creature support the theory that birds underwent an explosive period of evolution in the aftermath of the dinosaur extinction.

An Illustration of the Newly Described Early Paleogene Bird – Tsidiiyazhi abini

Picture credit: Sean Murtha

The Significance of Tsidiiyazhi abini

Scientists from the Bruce Museum (Connecticut), the Chinese Academy of Sciences and the New Mexico Museum of Natural History and Science (Albuquerque, New Mexico) have published a paper detailing the discovery of the fragmentary remains of a bird from the from the Nacimiento Formation of New Mexico.

The fossils date from 62.221 to 62.517 million years ago (Late Danian faunal stage of the Palaeocene Epoch), less than four million years after the extra-terrestrial impact event in the Yucatan Peninsula that marked the extinction of around seventy percent of all terrestrial life forms. The bird has been named Tsidiiyazhi abini, the name being derived from the local Navajo (Diné Bizaad) and it translates as “little morning bird”. At Everything Dinosaur, we have checked with the Bruce Museum to ensure we can relate the correct pronunciation, our apologies to any native Navajo speakers, but we think the name is pronounced – “City-ya-zee ah-bin-ih, with a focus on a “dee” sound in “City” rather than an emphasis on the “Tee” syllable.

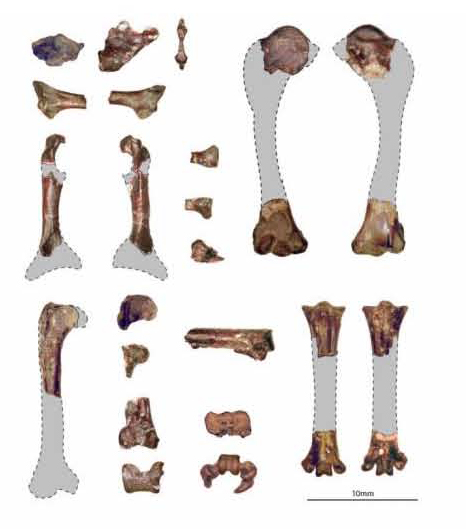

Tiny Fragmentary Fossils Tell the Story of Bird Evolution

Picture credit: PNAS

Supporting Evidence from “Molecular Clocks”

Palaeontologists are aware of the growing evidence from molecular studies into evolutionary relationships that suggests the birds diverged and evolved rapidly after the K-Pg extinction.

Unfortunately, the fossil record of birds is exceptionally poor. Very few fossils of birds are known from the Early Palaeocene. These animals tend to be small, their bones are delicate and the arboreal environment all tend to greatly reduce any fossilisation potential. The New Mexico fossil find is highly significant as T. abini has been assigned to the Sandcoleidae family, an extinct basal family of stem mousebirds (Coliiformes). The discovery of Tsidiiyazhi pushes the minimum divergence ages of as many as nine additional major neoavian lineages into the earliest Palaeocene, suggesting a very rapid evolution of Aves after the Cretaceous mass extinction.

Thanks to developments in genetics, scientists can study the evolutionary relationships of living organisms by comparing details of their genetics. A time when two, now distinct and separate but related organisms shared a common ancestor can be calculated using the idea that the molecules which form genes accumulate mutational changes in a clock-like, constant rate over geological time.

Researchers can use the changes in genetics of an organism to plot the approximate time when these species diverged from a common ancestor. The “molecular clock” data points to a period of rapid evolution for the Aves just a few million years after the extinction of the dinosaurs, fossil finds, such as the fragmentary fossils of Tsidiiyazhi abini provide further evidence to support this idea. In essence, the ancestors of all the major groups of modern birds we see today, had already evolved just a few million years after the last dinosaur (non-avian dinosaur) died.

Fossil Hunting – It’s a Family Affair

The tiny fossil bones were found by eleven-year-old twins Taylor and Ryan Williamson, the sons of Dr Tom Williamson, a palaeontologist specialising in the study of Palaeocene vertebrates based at the New Mexico Museum of Natural History and Science, who co-authored the scientific paper. Mousebirds are only found in sub-Saharan Africa today, however, these fossils help to confirm that these gregarious, fruit and seed eaters were much more geographically widespread in the past. Analysis of the delicate foot bones show that Tsidiiyazhi abini had evolved specialisations of the foot that let it reverse its fourth toe to better grasp and hold onto branches.

Twins Ryan and Taylor Williamson Found the Fossil Remains

Picture credit: Dr Tom Williamson (New Mexico Museum of Natural History and Science)

Tsidiiyazhi abini Adapted to Life in the Trees

The ability to reverse the fourth toe is referred to as semizygodactyly, this is an adaptation for life in the trees and the fossils of Tsidiiyazhi provides evidence that many groups of birds arose just a few million years after the K-Pg extinction event and had already begun to evolve specialisations of the foot bones to allow them to exploit different ecological niches.

The scientific paper: “Early Paleocene Landbird Supports Rapid Phylogenetic and Morphological Diversification of Crown Birds after the K–Pg Mass Extinction” by Daniel T. Ksepka, Thomas A. Stidham, and Thomas E. Williamson published in the Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America.

*Note

It is a common misconception that only the Dinosauria, marine reptiles and the Pterosauria were casualties of the mass extinction event that marked the end of the Cretaceous. Several other types of terrestrial vertebrate also suffered extinctions including the Aves and Mammalia. Many kinds of primitive bird along with different genera of mammals died out either at or shortly after the K-Pg boundary. Marine ecosystems were also badly affected and in addition, several families of plants did not survive this extinction.