Bucking the Trend – Luskhan itilensis

Writing in the academic journal “Current Biology”, a team of international scientists which includes Roger Benson and Valentin Fischer (Department of Earth Sciences, Oxford University), have published details of a new species of ancient marine reptile, a short-necked plesiosaur that bucks the trend for the Pliosauridae. Instead of being an apex predator, roles traditionally applied to monstrous animals such as Kronosaurus, Liopleurodon, the recently described (2013), Megacephalosaurus and Pliosaurus, the first of these large-bodied, big-skulled reptiles to be scientifically described, this new species probably hunted an entirely different sort of prey.

An Illustration of the Newly Described Pliosaurid – Luskhan itilensis

Picture credit: Andrey Atuchin

Feeding on Squid and Small Fish?

The rostrum of the newly described, highly unusual pliosaurid, is very narrow and it resembles the jaws of extant fish-eaters today such as the rare Gharial and the almost equally endangered (or, in the case of the Yangtze River Dolphin functionally extinct*) River Dolphins.

The Yangtze River Dolphin (Baiji)

The skull of a gharial from the Grant Museum of Zoology (London). Picture credit: Everything Dinosaur.

Picture credit: Everything Dinosaur

The long snout suggests that this newly described pliosaur, named Luskhan itilensis specialised in catching small fish and squid. Many palaeontologists suggest that the Pliosauridae were not capable of diving to great depths and they were confined to the Epipelagic zone (from the ocean surface to a depth of approximately 200 metres), whereas Sperm Whales, the largest toothed predators today, are capable of diving to much greater depths in pursuit of squid and other prey.

“Master Spirit of the Volga”

The fossilised remains of the marine reptile were initially discovered in the autumn of 2002 by one of the co-authors of the scientific paper Gleb N. Uspensky (Natural Science Museum, Ulyanovsk State University, Ulyanovsk, Russia). The material comes from the right bank of the Volga, near to the town of Ulyanovsk, the bedding plane from which the fossil material, including a 1.5-metre-long skull was excavated, dates from the Lower Cretaceous (Hauterivian faunal stage).

Luskhan itilensis

Pliosaurids (Pliosauridae) are a family within the Order Plesiosauria. They typically have large skulls, powerful jaws, a rigid body and propelled themselves through the water using their four flippers, although recent studies have shown that only the front pair of flippers were involved in propulsion. The flight of the Plesiosauria: The Plesiosauria, Penguins and Underwater Flight. The Plesiosauria swam in a unique way, not found in other vertebrates and now it seems that one group, the Pliosauridae, adapted to a wider range of ecological niches than previously thought.

Luskhan itilensis (the name means “Master Spirit of the Volga”), very probably did not specialise in hunting other marine reptiles, it filled a different role in the marine ecosystem of the Early Cretaceous.

Commenting on the significance of the discovery, Dr Valentin Fischer (Oxford University and lecturer at the University of Liège), the lead author of the study, stated that the specialised jaw:

“Is the most striking feature, which suggests that Pliosaurs had colonised a much wider range of ecological niches than previously thought.”

Not All Pliosaurs were Apex Predators

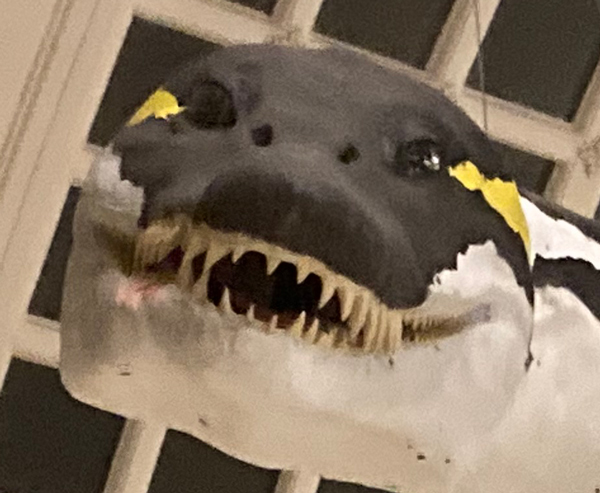

A close-up view of the pliosaur that is suspended above the ground floor at the Bristol Museum and Art Gallery (Bristol, England). The life-size replica was nicknamed “Deadly Doris”. Picture credit: Everything Dinosaur

Picture credit: Everything Dinosaur

Postcranial Plasticity (Repeatedly Evolving Long and Short-Necked Body Plans)

Of all the types of marine reptiles that evolved during the Mesozoic, the Plesiosauria was one of the most successful, having a fossil record of some 140 million years or so. During their long evolutionary history, plesiosaurs repeatedly evolved long and short-necked body plans.

In general terms, the Plesiosauria can be split into two sub-groups, the short-necked Pliosauridae and the longer-necked plesiosaurs, although this is an over simplification. The discovery of Luskhan, further muddies the evolutionary waters somewhat, as its skull shows affinities to the very distantly related Polcotylidae. A family of plesiosaurs, on the long-necked lineage side of the family tree, which evolved into fast-swimming fish hunters.

Study of the skull of L. itilensis indicates an evolutionary convergence of the cranial structure of typical polycotylids such as Dolichorhynchops. Distantly related animals evolve and ultimately resemble one another because they occupy similar ecological niches, such as the same hunting and feeding strategies.

The researchers conclude that the discovery of Luskhan itilensis demonstrates the ecological diversity of the Pliosauridae and reveals that these marine reptiles had a more complicated evolutionary history than their simple depiction as apex predators suggests.

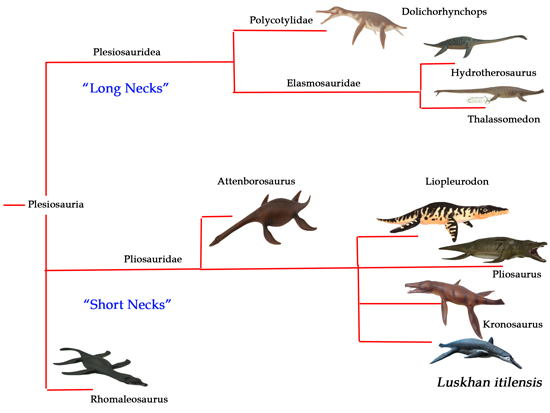

CollectA Models Help Demonstrate Cladistic Relationships Within the Plesiosauria

Picture credit: Everything Dinosaur with the utilisation of an illustration by Andrey Atuchin

The picture above shows a simplified view of the taxonomic relationships between members of the Plesiosauria. The length of the lines do not relate to geological age and the images of the animals are not to scale.

CollectA Prehistoric Life and Deluxe replicas have been used to illustrate the cladogram. To view the range of marine reptile models available from Everything Dinosaur: CollectA Deluxe Prehistoric Life Models.

CollectA Age of Dinosaurs Popular models: CollectA Prehistoric Life Figures.

The researchers conclude that the apex predator niche associated with the Pliosauridae does not necessarily reflect the diversity of this marine reptile family and that the pliosaurs repeatedly evolved long-jawed, specialist fish and squid catchers during their extensive evolutionary history.

* Functionally extinct – so few animals that there is no viable breeding population.

The Scientific Paper: “Plasticity and Convergence in the Evolution of Short-Necked Plesiosaurs” by Valentin Fischer, Roger B.J. Benson, Nikolay G. Zverkov, Laura C. Soul, Maxim S. Arkhangelsky, Olivier Lambert, Ilya M. Stenshin, Gleb N. Uspensky, Patrick S. Druckenmiller.

Visit the award-winning Everything Dinosaur website: Everything Dinosaur.

Leave A Comment