Tracking Down Australia’s Early Cretaceous Dinosaur Ichnofauna

A number of media outlets have covered details of the new scientific paper published in the “Journal of Vertebrate Palaeontology” that maps the extensive dinosaur tracks located on the Dampier Peninsula of Western Australia. The focus of many of these reports has been on the discovery of giant sauropod footprints, which at around 1.7 metres long, have been dubbed “the biggest dinosaur footprints in the world”.

Biggest Dinosaur Footprint in the World?

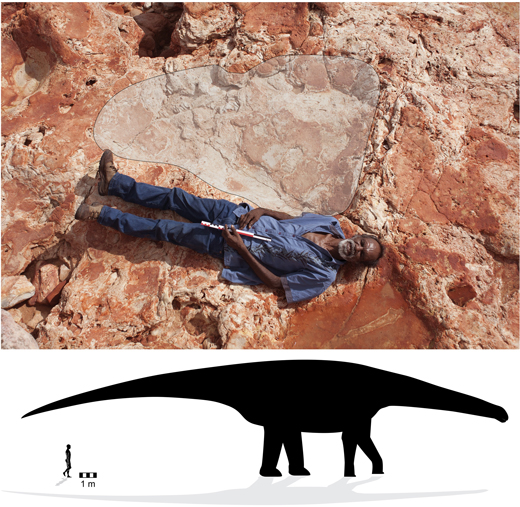

Picture credit: University of Queensland

Certainly, the picture of the individual print, with one of the field team, lawman Richard Hunter lying alongside, has captured the public’s imagination. However, some of the key findings of the academic paper have been somewhat overlooked in the mainstream media. In this article, we will briefly summarise some of the main points.

The Importance of the Broome Sandstones

The sandstone rocks of the Dampier Peninsula contain a vast amount of very well-preserved dinosaur tracks, prints and trackways. They have been studied periodically since the 1960s but were and remain, part of the myth culture related to creation for the indigenous people. The sandstones date from the Lower Cretaceous (Valanginian to Barremian faunal stages), that’s around 140 to 125 million years ago (mya).

The date of these rocks in Western Australia equates to around about the same time as the Wealden Supergroup was being formed, strata that is exposed in southern England, including the Isle of Wight and has yielded a wealth of dinosaur fossil material.

So, the trackways and prints preserved in Western Australia, permit scientists to compare and contrast the different dinosaur faunas that existed in different parts of the world, this is one of the key points from the mapping of the Australian tracks. In addition, these rocks are much older than the dinosaur fossil bearing strata in other parts of Australia, notably Queensland, the Winton area for example.

Dinosaur Tracks

The trace fossils preserved on the peninsula provide the main record of non-avian dinosaurs in the western half of Australia, this ichnofauna provides the only detailed glimpse of Australia’s Dinosaurian fauna during the first half of the Early Cretaceous.

A Dinosaur Thoroughfare – Extensive Dinosaurian Tracks Mapped

Picture credit: Queensland University

One of the implications for this study, is that the sauropod tracks provide scientists with an opportunity to research further how such large browsers and grazers shaped the environment and the ecosystem, just as elephants influence the flora to be found in Africa, where these extant herbivores are located in significant numbers (see photograph above, showing extensive Sauropodomorpha tracks – dinoturbation).

The Number of Tracks and the Different Types of Dinosaur They Represent

The research team, which was led by Dr Steve Salisbury (Queensland University), were invited by the area’s Goolarabooloo Traditional Custodians, to map and document the sacred trackways. From 2011 to 2016, the field team spent hundreds of hours recording, photographing, casting and mapping the trace fossils, a task made extremely difficult by the extent of the trackways and the fact that most of them were only exposed at low tide. Drones were used to provide an aerial view of the footprints, perhaps one of the most diverse Dinosaurian ichnofaunas found to date.

To read an article about the mapping work: Mapping the Dinosaur Heritage of Western Australia.

Forty-eight discrete Dinosaurian tracksites were identified in this area. Thousands of tracks were examined and measured in situ and using three-dimensional photogrammetry. Tracksites were concentrated in three main areas along the coast: Yanijarri in the north, Walmadany in the middle, especially around James Price Point and Kardilakan–Jajal Buru in the south.

Dinosaur Tracks and the Palaeoclimate

The researchers describe the palaeoclimate as a large braided river system within a flood plain that was periodically flooded, located close to the sea. Most of the dinosaur tracks are found in horizons that represent layers generated between the periodic floods.

Of the thousands of tracks studied, 150 could be assigned to the type of dinosaur likely to have made them. At least eleven and possibly as many as twenty-one different track types were recorded:

- Five different theropod tracks

- More than six types of sauropod tracks – including those 1.7 metre long prints left by the giant form.

- Six types of armoured dinosaur tracks

- Four types of ornithopod tracks

Eleven of these track types could formally be assigned or compared to existing or new ichnotaxa, whereas the remaining ten represent morphotypes that, although distinct, are currently too poorly represented to confidently assign to existing or new ichnotaxa.

One of the Newly Described Ichnotaxa – A Giant Eight-Metre-Plus Ornithopod Named Walmadanyichnus hunteri

Picture credit: Queensland University

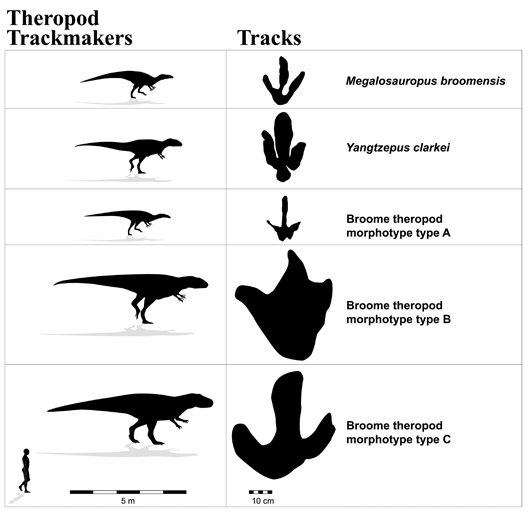

The Diversity of Theropod Dinosaur Tracks Mapped

Picture credit: Queensland University

Describing the Ichnotaxa

The researchers from Queensland University in collaboration with their associates at James Cook University, demonstrate that only two of the ichnotaxa described in this new paper, relate to already described dinosaur species. Tracks assigned to the small theropod Megalosauropus broomensis and the fleet-footed ornithopod Wintonopus latomorum have been described before.

The team have identified a total of six new ichnotaxa:

- One new theropod ichnotaxon – Yangtzepus clarkei (see illustration above).

- Two new ornithopod ichnotaxa – Wintonopus middletonae and the eight-metre-long giant Walmadanyichnus hunteri (see photograph of track in this article).

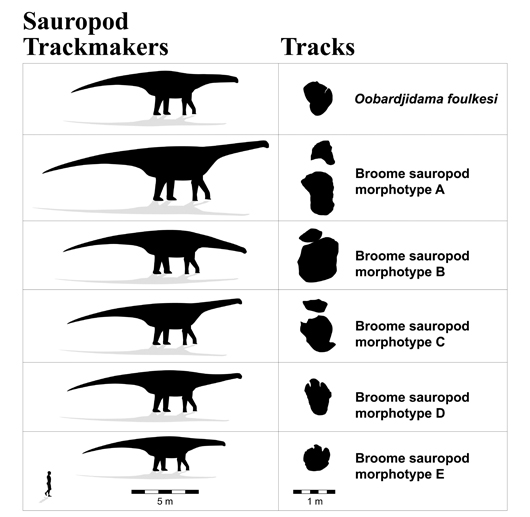

- One new sauropod ichnotaxon – Oobardjidama foulkesi (see illustration below).

- Two new thyreophoran ichnotaxa – Garbina roeorum and Luluichnus mueckei (see illustration further down this page).

Sauropod Trackmakers (Broome Sandstone)

Picture credit: Queensland University

The Importance of the Armoured Dinosaurs (Thyreophora)

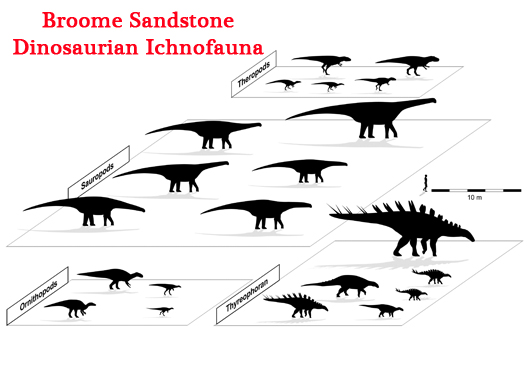

The researchers conclude that the trace fossils preserved on the Dampier Peninsula provide a unique insight into the dinosaur dominated biota of this portion of Gondwanaland in the Early Cretaceous. Both the sauropods and ornithopods seem to be diverse and abundant, with the armoured dinosaurs, the only fully quadrupedal bird-hipped dinosaurs recorded.

Importantly, the scientists report trackways associated with stegosaurids and overall, a higher density of armoured dinosaurs as well as many different types of theropod (carnivorous dinosaur), including at least two substantial meat-eaters (Broome theropod morphotypes B and C), which probably were apex predators. These large carnivores had plenty of prey, the paper, published in the “Journal of Vertebrate Palaeontology” also alludes to large bodied ornithopods as well as, giant sauropodomorphs.

Illustrating the Dinosaur Biota of the Dampier Peninsula Based on Tracksite Evidence

Picture credit: Queensland University with additional annotation by Everything Dinosaur

For models and replicas of stegosaurs, ornithopods and theropod dinosaurs: PNSO Age of Dinosaurs Models.

A Giant Stegosaurian Indicated by Dinosaur Tracks

Note the giant stegosaurid dinosaur, depicted in the illustration above. Some of the stegosaurid prints are around eighty centimetres long and approximately seventy centimetres across. This armoured dinosaur rivals the Broome sandstone sauropods in terms of size. Assigned to the ichnogenus Garbina, the trackways indicate a truly huge armoured dinosaur. Although Everything Dinosaur team members, having read the scientific paper, cannot find any specific size calculations for this dinosaur, the tracks are considerably bigger than those assigned to the ichnotaxon Garbina roeorum. This stegosaurid, could be one of the largest armoured dinosaurs yet described, with a body length exceeding eleven metres.

A Biota More Representative of the Late Jurassic than the Early Cretaceous

In many respects, the biota represented by the Broome sandstone tracks suggest a carryover of typical megafauna from the Late Jurassic, a time when the majority of Dinosaurian clades had a more cosmopolitan distribution prior to the break up of the super-continent of Pangaea. Although the fossil record for the Lower Cretaceous of Gondwana is very poor, a similar mix of taxa occurs in the Barremian–lower Aptian La Amarga Formation (Argentina) and the Berriasian–Hauterivian Kirkwood Formation of South Africa. The persistence of this fauna across the Jurassic-Cretaceous boundary in South America, Africa, and Australia might be characteristic of Gondwanan Dinosaurian faunas more broadly.

The Dampier Peninsula tracksites suggest that the extinction event that affected dinosaurs in the Northern Hemisphere across the Jurassic/Cretaceous boundary may not have been as severe further south (Gondwana). The disappearance of stegosaurids from Australia as indicated by the lack of fossils in younger Cretaceous strata and the apparent decline in Theropoda diversity by the middle Cretaceous indicates that, similar to what may have happened in South America, Australia passed through a period of faunal turnover from 140 mya to around 125 mya.

The Tracks of a Large Stegosaur (Garbina ichnogenus)

Picture credit: Queensland University

The World’s Biggest Dinosaur Footprint

If we briefly side step (no pun intended), the issue as to whether the Sauropodomorpha belong within the Order Dinosauria (see our article posted up on March 23rd, which explains about a potential re-classification of dinosaurs), is one of the Broome sandstone prints the biggest dinosaur footprint yet described?

To read an article from 2016 about a dinosaur titanosauriform print found in Mongolia: Giant Dinosaur Footprint from the Gobi Desert.

For an early article on the mapping of the Broome sandstone dinosaur tracks: Mapping the Dinosaur Heritage of Western Australia.

The Sauropodomorpha Track with a Scale Drawing of the Potential Size of the Dinosaur

Richard Hunter provides the scale next to the giant sauropod print. Scale depiction of dinosaur provided below.

Picture credit: Queensland University

The picture above shows the actual image released by Queensland University to illustrate the potential size of the dinosaur which made the series of prints which measure up to 1.7 metres in length.

Assessments of stride length suggest a sauropod dinosaur with a hip height of around 5.3 to 5.5 metres. The line drawing provides scale, potentially the long-necked dinosaur that made these tracks could have exceeded twenty-five metres in length.

Unable to Assign an Ichnogenus from the Sauropod Dinosaur Tracks

There is not enough information at the moment to assign an ichnogenus to this sauropodomorph, it has been named “Broome sauropod morphotype A”. Certainly, these 1.7 metre long prints are amongst the biggest yet found.

In October 2009, Everything Dinosaur reported on the discovery of a series of huge sauropod tracks in eastern France, to read about this: On the Trail of France’s Sauropod Big Foot.

The scientific paper: “The Dinosaurian Ichnofauna of the Lower Cretaceous (Valanginian–Barremian) Broome Sandstone of the Walmadany area (James Price Point), Dampier Peninsula, Western Australia”, by Salisbury, S. W., A. Romilio, M. C. Herne, R. T. Tucker, and J. P. Nair. Published in Journal of Vertebrate Palaeontology.

Visit Everything Dinosaur’s award-winning website: Everything Dinosaur.

the drawing of the big foot dino doesn’t fit the scale of a six-foot man fitting inside a print of the saropod’s front foot – either the man should be shorter or the dino bigger.