Ancient Bird Voice Box Sheds Light on the Voices of Dinosaurs

The Oldest Bird Voice Box – Honking in Antarctica

The identification of the vocalisation organ in the fossilised remains of a Late Cretaceous bird has provided scientists with an insight into the sounds you might have heard had you visited Antarctica around 66 million years ago. This bird voice box (called the syrinx), is the oldest known vocalisation organ from the Aves, it suggests that the bird – Vegavis iaai, very probably honked like a modern day goose, to which Vegavis is very distantly related. As such a structure has not been found in non-avian dinosaurs, the research team hypothesise that dinosaurs may have vocalised in a similar way to today’s ostriches which also lack a syrinx.

An Ancient Bird Voice Box

Ancient Antarctic Bird May Have Honked Like a Goose

Picture credit: Nicole Fuller/Sayo Art for University of Texas at Austin.

What is a Syrinx?

Most tetrapods such as humans and reptiles make noises by vibrating vocal folds in their larynxes, which is located at the back of the throat, but for most birds, the sounds that they make, be they, chirps, coos, quacks, tweets or honks are produced by a specially evolved organ called the syrinx, located in the windpipe where it branches left and right to the lungs. This organ is not constructed from bone but from calcified cartilage that typically does not fossilise well.

Writing in the scientific journal “Nature”, the research team which includes palaeontologist Dr Julia Clarke (University of Texas at Austin), describe the oldest syrinx found to date and compare it to the vocal organs of both extinct and extant Aves, as well as making comparisons with Alligators and in turn, making some intriguing conclusions about the sounds that dinosaurs may have produced.

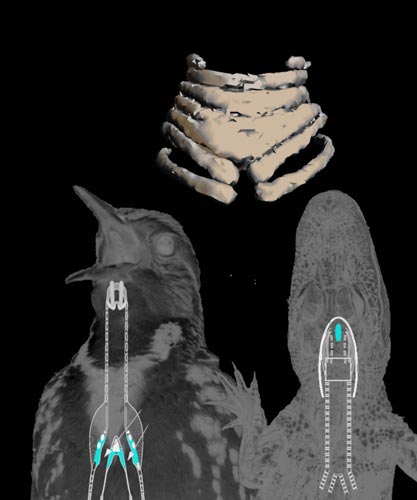

The Syrinx of Vegavis iaai is Constructed and Compared to that of Passerines and Alligators

Picture credit: Dr Julia Clarke (University of Texas at Austin)

Vegavis iaai

In 1992, a scientific expedition to explore the Upper Cretaceous deposits exposed on the isolated and remote Vega Island (a small island to the northwest of James Ross Island, on the Antarctic Peninsula), found the jumbled remains of an ancient bird. Several years later the concretion containing these bird bones was passed to Dr Julia Clarke to study.

Dr Clarke and her colleagues named and described Vegavis iaai in 2005, just one of a number of birds known from the highly fossiliferous strata that make up the Upper Cretaceous rocks that preserve an almost unbroken sequence from the Campanian faunal stage, through to the extinction of the dinosaurs into the first faunal stage of the Palaeocene (the Danian).

The Holotype Material for Vegavis iaai

Picture credit: University of Ohio

The Evolution of Dinosaur and Bird Vocalisation

In 2013, whilst working on a project on the evolution of dinosaur and bird vocalisation, Dr Clarke decided to take another look at the specimen’s vertebrae before returning it. Embedded in the rock, she discovered the tiny syrinx. This part of the Vegavis specimen was then carefully scanned using micro-CT technology, high energy X-rays that can penetrate the rock and reveal the structures of delicate fossils without damaging them.

Dr Clarke explained the reason for the research:

“While we have looked a lot at the evolution of the wings in birds, we have done very little with looking at the origin of what is perhaps one of the most striking characteristics of living birds – their songs.”

The three-dimensional computer model that was produced was then compared with the voice boxes of younger avian fossils and with a dozen living bird species. From this analysis, the team concluded that the shape of the syrinx in Vegavis iaai suggests that this ancient bird probably quacked or honked.

What Sound Did Dinosaurs Make Then?

Vegavis iaai has been classified as a member of the Anseriformes, a group of birds that consists of the waterfowl. Vegavis shared its environment with a number of terrestrial dinosaurs including theropods, ornithopods and possibly armoured dinosaurs. The apparent absence of a syrinx in dinosaur fossils of the same age, indicates that this organ may have originated late in the evolution of Aves, long after powered flight had evolved.

The researchers suggest that since there is no evidence of syrinx in the Dinosauria, dinosaurs may not have been able to make the sort of sounds that we associate with the close, living relatives the birds. Instead, dinosaurs may have been able to make closed mouth sounds, like the booming sound produced by today’s ostriches which also do not possess a syrinx.

Did Dinosaurs Vocalise in a Similar to Ostriches?

Picture credit: University of Texas at Austin/Motie Shirinkam

How Ostriches Vocalise

Male ostriches are able to produce a low frequency “booming” sound by inflating its neck to three times its normal diameter. Female ostriches can produce a hissing sound, but are not known to produce the “booming”. The discovery of the sound producing vocal organ in a fossil bird from the Late Cretaceous provides anatomical evidence that could lead onto scientists inferring aspects of prehistoric bird behaviour and social structure.

Vegavis Takes Flight Whilst a Male Theropod Dinosaur Vocalises Nearby

Picture credit: Nicole Fuller/Sayo Art for University of Texas at Austin

Visit Everything Dinosaur’s website: Everything Dinosaur.