Getting Our Claws into the Megaraptora

The Consequences of the Leggy Murusraptor

With the publication of the scientific paper announcing the discovery of Murusraptor (M. barrosaensis) in the on-line access journal PLOS ONE, palaeontologists might be one step nearer to identifying where in the Theropoda the Megaraptora clade fits. One thing is for certain, the Megraptoridae family and those dinosaurs closely related to them, are not closely related to the dromaeosaurids – the likes of Velociraptor.

An Illustration of the Newly Described Murusraptor barrosaensis

Picture credit: Jan Sovak (University of Alberta)

Before we discuss the phylogeny of Murusraptor and how it relates to other types of meat-eating dinosaur, lets quickly provide an outline of this newly described dinosaur.

Large Claws and Pneumatised Bones

The fossilised remains of a large, meat-eating dinosaur were spotted eroding out of a steep sandstone cliff that makes up a part of the Upper Cretaceous Sierra Barrosa Formation of Neuquén Province, southern Argentina. The permineralised, white bones were clearly identifiable against the sandy rock matrix, but extracting the specimen proved troublesome for palaeontologists Professor Phil Currie (University of Alberta) and co-author of the scientific paper, Dr Rodolfo Coria (Consejo Nacional de Investigaciones Científicas y Técnicas, Argentina).

Murusraptor Fossils

The first fossils were discovered during fieldwork sixteen years ago, but it has taken time to extract the disassociated fossil material from the various layers that it was deposited in. Having to work half-way up a remote canyon impeded the progress of the field team. The discovery of a single, poorly preserved manual ungual, (claw from the third finger of the hand), would hardly make the layperson scream “Megaraptor”, however, at forty-two millimetres long it is comparable in size to the third-finger claw of Megaraptor (M. namunhuaiquii), fossils of which come from Patagonia too. The real giveaway that these fossils represented a new member of the Megaraptoridae family were the air-filled (pneumatised) bones.

These light, air-filled bones are very reminiscent of modern birds and typical of the Megaraptora clade.

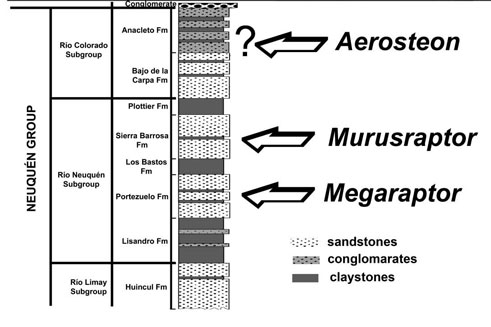

Biostratigraphic Diagram Showing Approximate Location of Patagonian Members of the Megaraptora Clade

Stratigraphic table and geologic section indicating the provenance of the megaraptorins recorded in the Neuquén group.

Picture credit: PLOS ONE

The diagram above shows some of the layers of rock that comprise the Neuquén Group of Upper Cretaceous strata that make up the Neuquén Basin of southern Argentina. A number of different types of meat-eating dinosaurs have been discovered in these rocks including Megaraptor (M. namunhuaiquii), the discovery of which led to the establishment of the Megaraptoridae, a new family of theropods.

Megaraptor Fossils

Megaraptor fossils come from the slightly older Portezuelo Formation of the Neuquén Group, the huge claw associated with Megaraptor was thought to have been a sickle-like toe claw, hence the initial description of a dromaeosaurid dinosaur. However, this claw was later interpreted as actually being from the hand (first digit). Another member of the Megaraptora clade, the nine-metre-long Aerosteon (A. riocoloradense), is known from slightly younger rocks. However, scientists remain uncertain as to where in the Order Theropoda these lightly built, large handed dinosaurs fit.

Where do the Megaraptoridae Fit In?

With the discovery of Murusraptor, palaeontologists hope to find out more about where within the Theropoda the Megraptoridae fits. Once the remains of Murusraptor were in the preparation laboratory, the researchers, Currie and Coria, were able to establish some interesting facts about this particular dinosaur. For example, they were able to conclude that the fossils represented a single animal, that it had come to rest lying on its right side and from the length of the tibia, it was a strong runner.

Two main theories have been put forward with regards to the Megaraptoridae and their phylogeny;

- Megaraptoridae family members and their close relatives making up the Megaraptora clade are the last surviving members of the once ubiquitous Allosauria clade. If, thanks to the discovery of Murusraptor, this is proved correct, then this would alter all the existing theories about the demise of the Allosauria.

- That Megaraptor, Murusraptor et al are members of the Coelurosauria clade and therefore related to modern birds, certainly studies of the breathing systems of similar dinosaurs Australovenator (Australovenator wintonensis) from Australia for example, indicate that these dinosaurs had respiratory systems very similar to extant Aves. If this theory proves to be correct then the likes of Murusraptor would be related to the tyrannosaurids.

Spinosaurids?

To complicate matters further, some of the anatomical traits found in the Megaraptora are similar to those of spinosaurids. This hints at a possible link to a much older group of theropod dinosaurs, the megalosaurs.

Palaeontologists Phil Currie (red shirt) and Rodolfo Coria Examine the Fossils

Picture credit: University of Alberta

“Wall Thief”

As for the name, the genus comes the Latin word “murus” which means wall, a reference to the fossil being located halfway up the wall of a canyon (see photograph above). The trivial name honours the location of the fossil find – Sierra Barrosa.

Southern Argentina has proved a happy hunting ground for vertebrate palaeontologists, especially those who specialise in studying the Dinosauria. Rodolfo Coria was one of the scientists who helped describe two of the most iconic dinosaurs of recent times the enormous Argentinosaurus and one of the largest, terrestrial predators ever to walk the Earth – Giganotosaurus. Last week, Everything Dinosaur reported on the describing of Gualicho shinyae, fossils of which come from the Huincul Formation, which underlies the strata from which Megaraptor and Murusraptor are known. Researchers are suggesting that this meat-eater was as a member of the neovenatorids, a branch of the allosaur family tree.

To read more about the tiny-armed Gualicho: Gualicho – Sticking Two Fingers Up at T. rex.

Dr Coria hopes that by studying the fossils of Murusraptor the mystery of the Megaraptor phylogeny will be finally resolved. He explained:

“Our current strategy includes two ways to get into this problem. One way to get close to the solution of this controversy is to review all different species and build a whole new data set, avoiding biases and preconcepts.”

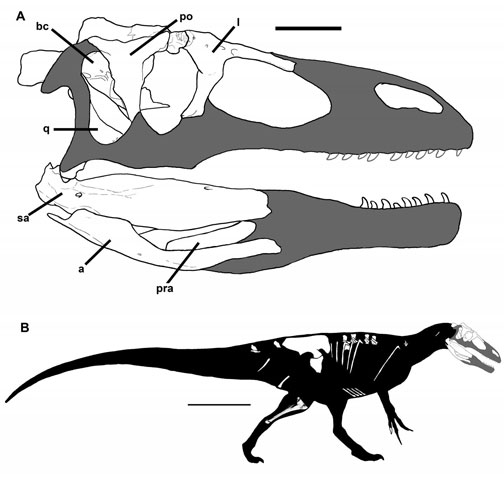

The Braincase

None of the bones associated with the front of the skull or the jaws were found, although some 31 teeth were recovered from the matrix. The largest teeth are more than twelve centimetres long. Bones from the back of the skull including those that make up the braincase were found. This is the only known braincase material from a Megaraptor-like dinosaur. A study of these braincase bones indicate that this specimen was a sub-adult, size estimates vary but this long-legged predator could have been between 6.5 and 8 metres long when fully grown.

Skeletal Drawing of M. barrosaensis

A drawing of the skull and body fossils associated with Murusraptor. Scale bars 10 cm (A) and 1 metre (B).

Picture credit: PLOS ONE

The picture above shows a close up of the skull bones (posterior part of the skull in right lateral view) and a skeletal drawing of the dinosaur (fossil bones in white).

A Super-cool Specimen

Professor Currie commented:

“This is a super-cool specimen from a very enigmatic family of big dinosaurs. Because we have most of the skeleton in a single entity, it really helps consolidate their relationships to other animals.”

Professor Currie went onto state:

“A lot of people have been waiting for this paper. When you have most of the skeleton, it takes a long time to do all the work on it. It turns out this animal is related to Megaraptor, found only thirty kilometres away in a different rock formation. The upshot was the more we looked, we could test whether Megaraptor was a dromaeosaur, which it isn’t in the strict sense, and what was thought to be the foot claws—the big can-opener claw of a dromaeosaur or raptor—were actually from the hands. We discovered all sorts of things through the course of our research.”

“A New Megaraptoran Dinosaur (Dinosauria, Theropoda, Megaraptoridae) from the Late Cretaceous of Patagonia” was published in the open-access journal PLOS ONE.

Note

Everything Dinosaur is switching to PLOS ONE from the previous nomenclature PLoS One.

Visit Everything Dinosaur’s website: Everything Dinosaur.