Unique Plesiosaur Fossil Provides Clue to Marine Reptile Breeding

Sea Monster in the Family Way

A paper detailing the research carried out on a superbly well preserved plesiosaur fossil has just been published in the scientific journal “Science”. The fossil, a long-necked marine reptile (plesiosaur) nick-named “Poly” could provide proof that such aquatic reptiles gave birth to live young – that they were viviparous.

Plesiosaur Fossil

The fossil, discovered on a ranch in Kansas in 1987 when fully excavated revealed something very unusual – amongst the large bones of the long-necked plesiosaur, there were the jumbled up remains of much smaller animal. Now, researchers have identified the mystery creature and published a paper into their research. “Poly” the plesiosaur may have been pregnant.

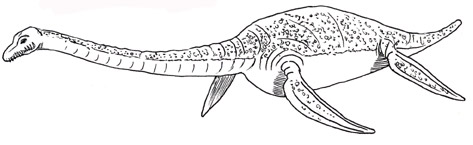

The Plesiosauria were a group of marine reptiles, ranging in size from about 3 metres in length to more than 15 metres long that lived in the Jurassic and Cretaceous. Many were long-necked, specialised fish eaters like the Late Cretaceous giant Elasmosaurus, but there were other types of plesiosaur. One group for example, were short-necked and became predators of other marine reptiles (pliosaurs).

An Illustration of a Typical Late Cretaceous Plesiosaur

Picture credit: Everything Dinosaur

If this fossil has been interpreted correctly and the small creature does resemble an unborn plesiosaur, then this sheds light on the mystery of how these large creatures bred. Some marine reptiles such as the extant turtles (Chelonia) are able to return to land and lay eggs. The females then return to the water abandoning the eggs to their fate. For plesiosaurs, returning to land may not have been an option, as certainly many later forms would have found locomotion on land with their flippers very awkward, and indeed out of the water their bodies would have been crushed by their own weight.

Commenting on the research, Xiao-Chun Wu, a palaeontologist at the Canadian Museum of Nature in Ottawa, stated that pregnant marine reptiles, although rare in the fossil record, were not that unusual. Dinosaurs living on land may have preferred laying eggs, but their aquatic kin, more closely related to modern lizards than to dinosaurs such as Triceratops and Diplodocus, had given up the terrestrial life. The flipper-ed plesiosaurs, in fact, seemed incapable of hauling themselves out of the water to find a spot on land, where it’s much safer for an egg. Researchers had discovered a number of other pregnant marine reptiles, including “fish lizards” – ichthyosaurs with several young inside their bodies. But they had yet to find a single fossil of a pregnant plesiosaur and could only speculate on how these predators that dominated the oceans of the Mesozoic reproduced.

A Plesiosaur Fossil on Display (Anterior View)

The teeth of the plesiosaur were well adapted for catching fish. Picture credit: Everything Dinosaur.

Picture credit: Everything Dinosaur

Fossils from Germany show a young ichthyosaur emerging from an adult. A number of fossilised bones of other babies can be seen in the body cavity. More than twenty years after the fossil was removed from the Kansas ranch, preparators have put together the bones and discovered the evidence for a viviparous plesiosaur.

The species Polycotylus latippinus a typical plesiosaur of the Western Interior Seaway is quite well known but no fossil like this has been found before. This specimen part of a new exhibition opened last month at the Natural History Museum of Los Angeles County, to celebrate the opening of the new dinosaur halls, measures five metres long and according to the research team, the more than a metre long youngster is not a meal but a baby inside its mum.

Polycotylus latippinus

Writing in the journal Science, the researchers state that the small creature has all the indications of being a baby, with its stubby limbs and big head. The embryos vertebrae, which in a more mature animal would be much more solid were still separated into smaller pieces. The little reptile had also been inside its mother when they met their end from an unknown fate, a thin layer of rock had fused the baby’s pelvis to the inside of its mother’s shoulder blade, something that wouldn’t be possible if the two had died side by side. O’Keefe estimates that the young marine predator was only about two-thirds developed.

Scientists have speculated that when the baby plesiosaur came to term, it could easily have exceeded 1.5 metres in length, or about a third of the mother’s body length. Having one big offspring that had a long gestation period is more akin to whale behaviour than to breeding behaviour associated with reptiles.

Most known lizards, snakes, and even ichthyosaurs produced many, even dozens of babies all at once. Marine mammals such as Orcas (killer whales) in contrast, have fewer young but also tend to be more diligent parents, suggesting that the fierce plesiosaur may have been a nurturer.

One of the researchers stated that plesiosaurs were not Orcas, but a few living reptiles also partake in mammalian-style baby making and rearing. For example, some species of Australian skinks, for instance, live in warrens with as many as seventeen relatives. Their stable family home makes child care convenient. Poly’s briny lagoon, which extended along what’s now the Mississippi River into Kansas, may have been equally calm, a researcher commented:

“It is plausible that plesiosaurs lived in some fairly stable environments in which they didn’t move around too much.”

Alternatively, plesiosaurs may have migrated to a quiet, shallow lagoon type of environment specifically so that they could give birth and spend the first few weeks in relative safety with their offspring. Although, given the state of the fossilised bones of the embryo, it is likely that the gestation period had sometime to go before this mother would give birth.

However, other palaeontologists have challenged the viviparous view, claiming that the plesiosaur baby is in fact the remains of a meal. This would explain why only one small plesiosaur was found inside the body cavity.

Kenneth Carpenter, a palaeontologist at Utah State University believes that “Poly” should not be considered as an example of live birth in plesiosaurs. The young reptile in her abdomen is missing a few bones, and he suspects that “mum” lopped them off when she fed on the unfortunate youngster. Many modern-day reptiles similarly feast on juveniles, even those from the same species:

He stated:

“This is a stronger case for cannibalism than it is for live birth.”

For models and replicas of plesiosaurs and other marine reptiles: Plesiosaurs and Prehistoric Animal Figures from CollectA.