New Research into Late Cretaceous Pterosaurs – Not Flyers but Stalkers

New research published today, led by scientists from the University of Portsmouth has concluded that many of the large pterosaurs of the Late Cretaceous may have had a completely different lifestyle than previously thought. Large azhdarchid pterosaurs may have been terrestrial hunter. Animals may have been stalked by a flock of Quetzalcoatlus! They may have been walkers, not long-distance gliders, patrolling the great fern plains snatching up prey with their long toothless beaks.

Pterosaurs are not Dinosaurs

Pterosaurs are not dinosaurs, but reptiles that shared a common ancestry with the dinosaurs (the Archosauria). The first fossils of these flying reptiles date back to the middle of the Triassic, around 230 million years ago. They evolved into a myriad of forms, from long-tailed pterosaurs with relatively short bodies and stubby wings to the huge, short-tailed pterosaurs of the Late Cretaceous with many species having wingspans in excess of 8 metres.

Pterosaur Success

These flying reptiles were very successful during the Mesozoic period, although their numbers and the diversity of the group declined sharply towards the end of the Cretaceous. Scientists have speculated about why this group of animals declined, perhaps it was because of competition from the rapidly diversifying birds. After all, feathered flyers would have a number of advantages over gliding or flying reptiles that were powered by flaps of skin, living tissue membranes, reinforced with tough, elastic fibres which were supported by an elongated fourth finger.

To read more about pterosaurs competing with birds: Did the Birds wipe out the Pterosaurs?

The last of the flying reptiles were giants, animals like Quetzalcoatlus and Pteranodon. Interestingly, Pteranodon fossils (the family is called Pteranodontidae) have been mainly found in marine sediments. This indicates that these animals lived in coastal habitats and they were probably piscivorous (fish-eaters). In contrast, fossils of the genus Quetzalcoatlus (family is called the Azhdarchidae), are associated with sediments that were laid down inland; far away from a marine environment. The fossil evidence revealed so far on the Azhdarchidae pterosaurs does not point to them being typical fish-eaters and there are some subtle differences in their anatomy when compared to other large pterosaurs that may indicate a totally different ecological niche for these bizarre creatures.

Stalked by a Flock of Quetzalcoatlus

This new study carried out by Mark Witton and Dr Darren Naish has reviewed the current data and published fossil material on the azhdarchids. They have come to the conclusion that these animals may have been the prehistoric equivalent of ground-feeding birds such as the ground hornbills and some types of modern stork.

The study of azhdarchid anatomy, footprints attributed to these pterosaurs and the distribution of their fossils by the research team shows that the coastal glider, fish-eater stereotype of large pterosaurs does not necessarily apply to this particular family of flying reptiles. Their review provides evidence that some types of azhdarchids were strongly adapted for terrestrial life. According to the review of the fossil bones of azhdarchids the scientists have concluded that they were better adapted for walking than other types of flying reptile because they had long limbs in proportion to their bodies. Their light, skulls ending in a sharp, pointed but toothless beak would have been well suited for picking up small animals and other food from the ground. They would then have manipulated their food in the huge beak before swallowing it whole (probably head first like many species of ground hunting birds do today).

Azhdarchid Pterosaurs

Azhdarchids such as Quetzalcoatlus, a huge pterosaur with a wingspan of approximately 12 metres have big eye sockets in their skulls indicating large eyes, with perhaps telescopic vision, although this can only be speculated at the moment. The placement of the eyes to the side of the head but looking forward would have enabled these large animals to judge distance accurately. Some palaeontologists believe that these physical attributes would have helped Quetzalcoatlus scan lakes for fish on the surface or perhaps to search the terrain below them for carcases to scavenge as they flew high above, just like vultures do today. However, this new paper reports on how effective these adaptations would be for spotting and grabbing prey as these huge reptiles wandered around on all fours.

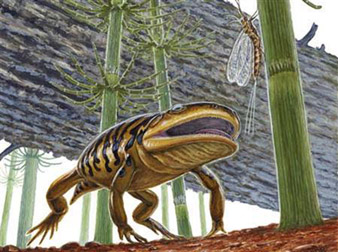

An Artist’s Impression of Quetzalcoatlus Searching for Food

Picture credit: Mark Witton

The illustration above shows a flock of Quetzalcoatlus moving through an extensive fern plain predating on small animals including baby dinosaurs hiding in the undergrowth. The wings may not have been particularly effective for flying with rapid wing beats, but could have served as giant shields to prevent potential prey escaping. Moving in a line they could have co-operated together in order to stop any small animals avoiding being eaten. Such behaviour is seen in the group hunting of some pelican species today.

If the azhdarchids did have this sort of environmental niche, it is possible to imagine them following behind the herds of hadrosaurs and ceratopsians snatching at the small creatures such as lizards, mammals and small dinosaurs disturbed by these huge herbivores as they wandered the plains.

It would be beneficial for both types of animals, the ceratopsians for example could rely on the pterosaurs with their keen eyesight to keep a look out for potential predators such as tyrannosaurs, whilst the azhdarchids could rely on the horned dinosaurs to flush out potential prey and with their horny beaks they could crop small trees and bushes helping to maintain the plains as an ideal hunting habitat for these large flying reptiles.

Loose relationships such as these can be observed on the Savannah of Africa with herds of Zebra tolerating Ostriches, as the bird’s sharp eyes can help to keep watch for predators, permitting the Zebras to remain with their heads down for longer grazing.

The Azhdarchidae

Escaping from any potential threats could pose a problem for such large pterosaurs, it had been thought that these animals needed to live by cliffs so that their take-off could be assisted by gusts of wind rising from natural obstacles. It has also been suggested that these animals used thermals, hot air rising from the land to help them gain altitude in a manner similar to vultures and birds such as condors. Being able to take to the air was perhaps their only effective means of defence against predators. Although the largest species of Azhdarchidae so far described Q. northropi had a wingspan of 11-12 metres it weighed little more than 80-90 kilogrammes, so it would have been no match even for a small or sub-adult member of the tyrannosaur family. The relatively long hind-limbs could have been quite powerful and capable of providing the impetus and initial lift to help these animals take to the air, but again the fragmentary fossil evidence of the Azhdarchidae prevents much further work on the muscle mass associated with the femur or the bones of the lower leg.

The More Typical Pose of an Azhdarchid Pterosaur

A model of the giant Pterosaur Quetzalcoatlus.

Picture credit: Everything Dinosaur

The picture above shows a model of a Quetzalcoatlus a typical large, long-necked azhdarchid pterosaur of the Late Cretaceous.

To view a range of prehistoric animal models including pterosaur figures: Dinosaur and Prehistoric Animal Models.

Despite the lack of fossils it is now known that the azhdarchids had a substantial geographic distribution. Fossils have been found in China, Japan, Jordan, Morocco, Russia, Senegal, Spain, North America and Uzbekistan. Indeed, this type of pterosaur was named from the Uzbek word for dragon.

Dr Naish said: “Azhdarchids first became reasonably well known in the 1970s but how they lived has been the subject of much debate. Originally described as vulture-like scavengers, they were later suggested to be mud-probers (sticking their long bills into the ground in search of prey), and later still suggested to make a living by flying over the water’s surface, grabbing fish.

Other lifestyles have been suggested too. These lifestyles all seem radically divergent so Mark and I sat down and carefully examined the evidence and we argue that azhdarchids were specialised terrestrial stalkers. All the details of their anatomy, and the environment their fossils are found in, show that they made their living by walking around, reaching down to grab and pick up animals and other prey.”

The two researchers studied fossils in London, Portsmouth and Germany and compared the anatomy of azhdarchids with those of modern animals, that fill the sort of ecological niches previously thought to have been occupied by the azhdarchids in the Campanian and Maastrichtian faunal stages of the Late Cretaceous. This showed that azhdarchids were strikingly different from mud-probers and animals that grab prey from the water’s surface while in flight.

Dr Naish said: “We also worked out the range of motion possible in the azhdarchid neck: this bizarrely stiff neck has previously been a problem for other ideas about azhdarchid lifestyle, but it fits with our model depicting this group as terrestrial stalkers”.

This particular group of pterosaurs have characteristically long-necks which are relatively stiff and immobile. Such an anatomical arrangement would fit the hypothesis put forward by Mark Witton and Dr Naish as with a terrestrial, stalking habit all these animals would need to do to feed would be to raise and lower the beak in a vertical line to the ground. Studies of the bones in neck vertebrae indicate that they could certainly do this. The necks were also quite strong, able to support the head and a beak up to 1 metre long in the larger species, certainly some of these neck vertebrae were an impressive size, a single neck vertebrae, discovered in Jordan in 1943 and believed to have belonged to an azhdarchid was over 60 cm long.

Strong but Inflexible Necks

The strong, inflexible neck also provides evidence to support another theory about the diet of these animals, that they were scavengers operating like vultures. The huge wings allowing them to glide effortless across the land, coupled with their excellent eye-sight would have made them superb spotters of carrion. Once found, the carcase could be ripped open by a few strong blows of that strong, dagger-like beak. These pterosaurs if they were scavengers living on the remains of dinosaurs would have had to break through many centimetres of tough hide to reach the flesh underneath. The sharp beaks, powered by strong neck muscles could be capable of doing this. A long neck would enable these creatures to reach deep inside a carcase to feed.

In the scientific paper published today other aspects of azhdarchid anatomy are discussed. Consideration is given to their relatively small padded feet which the British researchers claim would not have been suited to walking around the muddy shores of lakes, probing for burrowing shellfish and crabs. This work casts further doubt on the mud-probers hypothesis.

In their study the researchers calculated that over 50% of all the known azhdarchid fossils are from sediments laid down inland, away from marine environments. Significantly, the few articulated azhdarchid fossils have all been discovered in areas believed to have been a long way from saltwater when the animal perished. The relative completeness of these finds indicate that the carcase may not have been transported very far before finally coming to rest and starting the preservation process. This might show that the azhdarchids were very much creatures of the land and not marine environments.

From our own observations of birds such as the Marabou stork (Leptoptilos crumeniferus) on the Masai Mara, it is possible to imagine animals such as the azhdarchids filling this niche in the food chain. Although it is worth pointing out that in the case of the Marabou stork, it scavenges carcases as well as actively hunting in the grass and reed beds of Africa. Perhaps the azhdarchids such as Quetzalcoatlus and its close relative Montanazhdarcho were also opportunists grabbing a meal in a variety of ways. If they were warm-blooded and this is quite likely given the pterosaur ability to fly, then they would have had to consume perhaps as much as ten times the food of a similar sized cold-blooded animal like one of the large crocodiles that also lived at the end of the Mesozoic.

No doubt the debate will continue for sometime to come. The paucity of the fossil record for large pterosaurs does not help, there have been several attempts to review the Azhdarchidae in order to establish relationships between genera. What is compounding the problem is that scientists are not really sure of the size of many genera so far described, many from only fragmentary remains. For example, a single bone from the Dinosaur Provincial Park Formation in Alberta, Canada could be a femur indicating an animal with a wingspan of no more than 3 metres across. However, if the same bone is described as a wing metacarpal, or an arm bone (ulna or radius) then with a bone diameter in excess of 60 mm this would indicate an immense animal with a wingspan approaching the size of the largest pterosaurs known (wingspan in excess of 12 metres).

Such are the difficulties that surround research into these amazing animals. Work on the Campanian faunal stage deposits in Alberta indicates the presence of a least three genera of azhdarchid, with wingspans from 2.5 to up to 11 metres across all living in the same area at the same time. However, the incomplete and scarce remains recovered so far mean that palaeontologists are unable to rule out the possibility that the pterosaur fossils found in this area actually represent just one genus and that the bones represent animals of different ages or perhaps even males and females. Bennett (1992) has made a convincing case for sexual dimorphism in Pteranodon, with males believed to be up to twice the size of adult females.

The truth is, until many more fossils of azhdarchids are found then the speculation on their diet and lifestyle and even some aspects of their basic anatomy are going to continue. Ten years ago for instance, Clark et all published a paper on a study of the posture of pterosaurs, this team concluded that the metatarsal-phalangeal joints of the azhdarchids (those bones that connect the ankle to the toes) did not seem well suited to a cursorial lifestyle.

This article has been produced using material from the Public Library of Science (2008, May 28) – Giant Flying Reptiles Preferred To Walk.

The work of Bennett referred to in the text is from a paper published in 1992 in the Journal of Vertebrate Paleontology – Sexual dimorphism of Pteranodon and other Pterosaurs with Comments on Cranial Crests.