Teeth in Mammals hold the Key to Identification

Mammals have been around for approximately 210 million years, the fossil record indicates that they first appeared in the Late Triassic. Admittedly, mammals of the Mesozoic were small, many of them were shrew-like creatures, filling the niches not exploited by the dominant reptiles. It has been speculated that many of them were nocturnal and that they lived inconspicuously in burrows or rock crevices keeping out of the way of the larger terrestrial reptile groups. Mammal teeth fossils can play a key role in identification and taxonomy.

The Age of Mammals

Following the mass extinction event that ended the Mesozoic era and heralded the start of the Cenozoic, the diversity of reptiles never recovered. Instead in the animal kingdom the mammals, birds and insects seemed to have rapidly evolved to exploit the new environments and ecological niches opened up by the mass extinction. In the plant kingdom the angiosperms (flowering plants) continued to go from strength to strength dominating plant life on Earth. The naming of the Cenozoic is appropriate as translated from the Greek the word means “new life”.

The evolutionary relationships between different types of mammals is unclear, the paucity of the fossil record accounts for this. Indeed, mammals may have been more common in the Jurassic and Cretaceous than is indicated by the fossil evidence, but the poor preservation potential of these animals limits the amount of fossil specimens likely to be found.

Mammals would have had a limited preservation potential as being small any carcases would soon have been scavenged and the relatively tiny, delicate bones would have been unlikely to survive the fossilisation process. Inhabiting environments such as deserts, scrubland and woodland would have limited the opportunities for fossilisation even further (these environments are not conducive to fossil forming conditions in normal circumstances).

Mammal Teeth

However, teeth made from enamel, the hardest substance in the body, can survive fossilisation and even though mammal teeth fossils are exceptionally rare they can provide vital information as to the appearance of the entire animal and what it ate. Many of the extinct early mammal groups are known only from isolated teeth and fragments of jawbones. Unlike the simple teeth of reptiles (even dinosaurs had relatively simple teeth compared to mammals), mammalian teeth are differentiated by their shape. The shape of the teeth dictates their function.

Incisors and canines at the front of the mouth are used for obtaining food and holding on to it. The cheek teeth, towards the back of the jaw are the food processors, grinding up the food as the first part of the digestion process.

To read more about an example of mammalian teeth from the Mesozoic:

Very Ancient Udders! Mesozoic cow discovered in India.

To learn how such specimens are dated (often dated by matrix and sediment data found in-situ with the main specimen):

Dating the Mesozoic Cow! It was the fish and ostracods that did it.

These cheek teeth, the molars and pre-molars have distinctive patterns of cusps, ridges and furrows which in combination with the movement of the jaws allows for efficient cutting and chewing. These distinctive teeth, their wear patterns and size can provide palaeontologists with a surprising amount of data. An entire genus could be described from the evidence of a single fossil tooth.

Teeth in Mammals – A Key to Identification

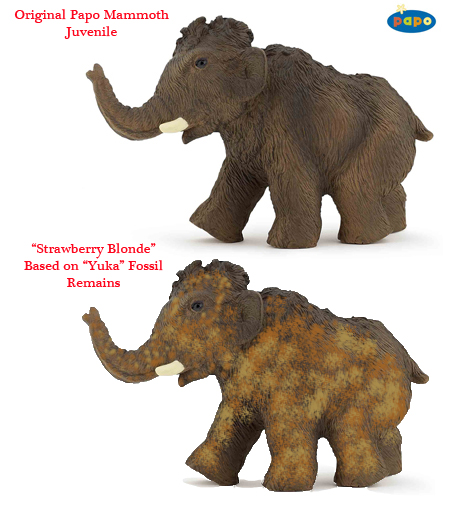

A close-up view of the mouth of the Steppe Mammoth. Mammalian fossil teeth can be pivotal in identification. Picture credit: Everything Dinosaur.

Picture credit: Everything Dinosaur

The picture (above) shows a close-up view of the teeth of the Eofauna Steppe Mammoth model, a company with a deserved reputation for producing excellent prehistoric mammal models.

To view the Eofauna model range: Eofauna Scientific Research Models.

Teeth Morphology

Teeth morphology can also help scientists distinguish between different types of mammals such as monotremes, marsupials, placental mammals (extant groups) and the now extinct group the multituberculates. The multituberculates (named after the multiple cusps or tubercles on their molar teeth), were a relatively successful group of Mesozoic and early Cenozoic mammals.

Fossil evidence has been found in Middle Jurassic strata indicating that they evolved around 160 million years ago. They were probably nocturnal, herbivorous with a burrowing habit, superficially resembling many of the rodents found today. Most of the fossil evidence has been gathered in the northern hemisphere it is not clear whether these mammals existed in Gondwanaland.

Multituberculates probably gave birth to very small, under-developed young. This associates them with Marsupials. This information has been assumed by studying the relatively few fossils of bones from pelvic area. In many specimens, the pelvic area is quite narrow and this would make the ability to give birth to larger fully formed young unlikely. This many group went into steep decline towards the end of the Palaeogene, becoming extinct approximately 35 million years ago.