British Scientists use Dinosaur Thigh Bones to Tell Boys from Girls

A team of British scientists have concluded that the shape and size of muscle attachment scars seen on the upper hind limb bones (femur) of dinosaurs may provide clues that will help them distinguish between males and females. The technique, if proven, may help palaeontologists understand more about some of the ornate frills and crests that some dinosaurs had – anatomical differences between male and female dinosaurs of the same species.

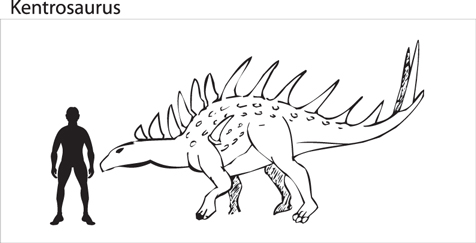

Kentrosaurus

This new study and its implications is discussed in a paper published in the scientific publication the Journal of Vertebrate Palaeontology. How to tell male from female dinosaurs apart has long been a subject of controversy for many scientists. Unfortunately, with in most cases, only the fossilised bones to study, determining which dinosaur fossils represent boys and which ones are girls is quite difficult – but not impossible. For example, studies into the structure of some large hadrosaur bones and other dinosaur remains has led to the identification of medullary bone tissue, calcium rich deposits inside the bones which females use to draw the reserves of calcium required to produce bird egg shells. If a cross-section of dinosaur bone shows evidence of medullary bone tissue, this is significant evidence to suggest that the bones come from a female. However, this is a costly and destructive technique so if another fool-proof method could be identified, one which was based on an external observation and comparison of fossil material then so much the better.

To read more about the examination of internal fossil bone structures to identify female dinosaurs and matters related to ontogeny (growth rates in dinosaurs): Research Shows that Dinosaurs May have Grown Quickly and Died Young.

Co-author of the research paper Susannah Maidment of the Natural History Museum (London) stated:

“Bones are shaped by the muscles that attach to them, so difference in the shape or size of muscle attachments on the leg bones suggests differences in the muscle mass of the animal that the leg belonged to.”

The dinosaur chosen for the study was the stegosaurid Kentrosaurus, (K. aethiopicus), known from Upper Jurassic (Kimmeridgian faunal stage) strata from the famous Tendaguru site in Tanzania (Africa). Several specimens of this particular ornithischian dinosaur have been discovered, including many individual bones, most famously by German led expeditions that explored the Tendaguru Formation between 1909 and 1912. Something like the bones from seventy different kentrosaurs have been found to date. The scientists analysed the shape and muscle attachment scars on fifty femora (the plural of femur – thigh bones).

Closely related to the American Stegosaurus, Kentrosaurus had two pairs of small plates that ran along its back and neck. The plates became pairs of spikes as they continued down the body to the tail. A larger spike was found on the shoulder blade, providing protection from attack, although some scientists believe this spike was actually positioned over the thigh.

A Scale Drawing of Kentrosaurus

Picture credit: Everything Dinosaur

Maidment went on to comment:

“We used a method that examines shape differences in the leg bones, and we were able to show that at the top end of the bone, where some of the hip muscles attach, there are shape differences. We were able to group the adult bones into two statistically significant groups: that is all adult bones had one morphology or the other morphology.”

Fossils for juvenile dinosaurs and sub-adults, did not fall into the groups, indicating that the bone shape differences didn’t occur until adulthood when the young dinosaurs likely evolved their secondary adult characteristics such as distinctive crests, frills and horns as in the case with other ornithischian dinosaurs. If the two morphologically exclusive groups of bones represent adult males and adult females, then this is a start, but at the moment the researchers are unable to conclusively state which group were males and which female.

Maidment added:

“We’ll probably never know that unless a complete, spectacularly well preserved specimen of Kentrosaurus is found with an egg in its oviduct.”

Notwithstanding the obvious problems of trying to determine the status of dinosaur fossils approaching 150 million years old, this new technique provides researchers with a tool that can be used to complement other observed differences among members of the same dinosaur species.

The scientists therefore now suspect that the unusual spikes and armoured plates found on stegosaurs may have had unique particular shapes, depending on whether the individual was a male or female. Since there are only two specimens of Stegosaurus with complete rows of armour, the researchers cannot yet assess those probable differences between the boys and girls. However, such differences are only likely to be trivial and superficial in the opinion of Everything Dinosaur’s experts. The primary function of spikes is not for displaying difference amongst genders but for defence, natural selection would not necessarily lead to armour and defensive weapons being selected for to permit gender differentiation, although it could be argued that in extant deer, the antlers of the bucks are very different from those of the does (if they have antlers) and indeed there is huge variation in antler shape and size amongst individuals.

Ken Carpenter at the Denver Museum of Nature and Science has down some work on tyrannosaur pelvises. He and a number of other researchers have identified “gracile” and “robust” forms of T. rex. Could these differences have something to do with the need to store and pass eggs in the females? It is certainly a well-written and interesting paper and we shall see how this Kentrosaurus focused story evolves.

To view models and replicas of Kentrosaurus (whilst stocks last): Wild Safari Prehistoric World Models and Replicas.

Leave A Comment