New Study Suggests a Stiff Skull Helped T. rex Crush Bones

Stiff Skull Helped T. rex Crush Bones

Numerous research papers have been published about those monstrous jaws and huge skull of Tyrannosaurus rex. Many of the studies have examined the biomechanics in a bid to better understand the bite forces that this Late Cretaceous terror could generate.

It is widely accepted that T. rex had a bone crushing bite, but just how it managed to crush the bones of a Triceratops or an unfortunate Edmontosaurus without damaging itself, has puzzled palaeontologists. A new study, published in the journal “The Anatomical Record”, suggests that the T. rex skull was much stiffer than previously thought, much more like a crocodile skull or that of a hyena than a scaled-up, flexible bird skull.

New Study Suggests T. rex Had a Stiff Skull

Picture credit: Amanda Kelley

Studying the Skull of Tyrannosaurus rex

One of the co-authors of the study, Kaleb Sellers of the Missouri University School of Medicine explained:

“The T. rex had a skull that’s about six feet long, five feet wide and four feet high and bites with the force of about six tons. Previous researchers looked at this from a bone-only perspective without taking into account all the connections, ligaments and cartilage that really mediate the interactions between the bones.”

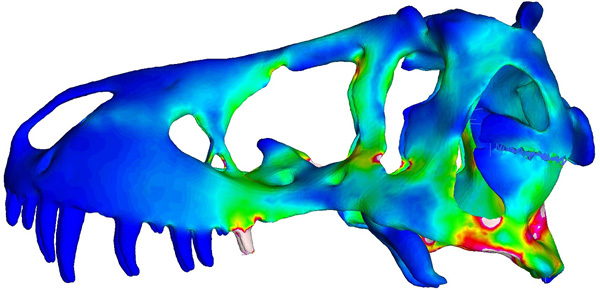

Computer Generated Models Examined Stresses in the Upper Skull with a Focus on the Palatal Area

Picture credit: University of Missouri

Looking at the Roof of the Mouth (Palatal Area)

The scientists, which included Kevin Middleton of the Missouri University School of Medicine, M. Scott Echols of The Medical Centre for Birds, Lawrence Witmer of Ohio University and Julian Davis (University of Southern Indiana), used a combination of anatomical study, computer modelling and biomechanical analysis assessing the skulls of a gecko and a parrot to examine how the skull of this apex Late Cretaceous predator was adapted to deliver such powerful bites.

Casey Holliday, from the University of Missouri, who also helped to write the scientific paper commented:

“Dinosaurs are like modern-day birds, crocodiles and lizards in that they inherited particular joints in their skulls from fish — ball and socket joints, much like people’s hip joints — that seem to lend themselves, but not always, to movement like in snakes. When you put a lot of force on things, there’s a trade-off between movement and stability. Birds and lizards have more movement but less stability. When we applied their individual movements to the T. rex skull, we saw it did not like being wiggled in ways that the lizard and bird skulls do, which suggests more stiffness.”

A Functionally Akinetic Skull

Tyrannosaurus rex is considered to have one of the strongest bites of any terrestrial tetrapod. There are lots of scientific papers and other literature that document this evidence. Over the years, Everything Dinosaur have produced many articles on this subject area, including a blog post that summarised research published in “Biology Letters” – T. rex had a Bite More Powerful than any Other Land Animal.

The Skull and Jaws of Tyrannosaurus rex

Picture credit: Everything Dinosaur

Everything Dinosaur stocks a huge range of tyrannosaur models.

To view models and replicas on the company’s website: Dinosaur and Prehistoric Animal Figures.

Tyrannosaurus rex – A Biomechanical Paradox

The skull of T. rex has been regarded as quite flexible by palaeontologists, that is, it exhibits a degree of cranial kinensis. The joints in the skull are quite mobile and flexible in relation to each other and the animal’s braincase. This contradicts with what is seen in many extant tetrapods who are known to have a powerful, bone smashing bite.

Alligators and hyenas for example, have relatively robust and inflexible skulls, when compared to the skull of a bird or a lizard. If the T. rex skull was flexible but still capable of delivering an enormous bite force, this is a biomechanical paradox, it defies a logical explanation. Furthermore, the greatest bite forces measured for crocodilians and hyenas (ourselves for example too), are detected towards the back of the jaws, whereas, in Tyrannosaurus rex, the largest bite forces that have been calculated are recorded at the front of the jaws.

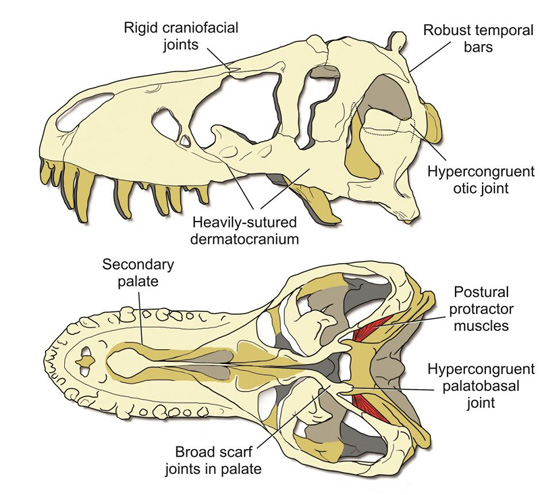

This New Analysis Suggests that the T. rex Skull was Functionally Akinetic

Picture credit: University of Missouri

The researchers identified a number of adaptations in the cranium of T. rex to support the idea that the skull was not as flexible as previously thought. The scientists postulate that the skull was functionally akinetic (much stiffer than previously surmised).

Research that Provides a Better Understanding of Our Own Joints and Bones

This study will help palaeontologists to better understand the function of tyrannosaurid skulls and the researchers postulate that their findings can help advance human and veterinary medicine.

The study, “Palatal biomechanics and its significance for cranial kinesis in Tyrannosaurus rex”, was published in The Anatomical Record. Authors include Kevin Middleton of the Missouri University School of Medicine; M. Scott Echols of The Medical Centre for Birds; Lawrence Witmer of Ohio University and Julian Davis of University of Southern Indiana.

Everything Dinosaur acknowledges the assistance of a press release from the University of Missouri in the compilation of this article.

The Everything Dinosaur website: Everything Dinosaur.