Everything Dinosaur’s Top Blog Posts of 2018 (Part 2)

Today, we conclude our look at our most memorable blog posts of 2018, with a review of blog posts from July through to December. Since we try to post something up every day, there are certainly a lot of articles to choose from, in our previous posting covering the first six months of the year, we certainly came up with an eclectic mix: Top Blog Posts of 2018 (Part 1), part two is very much cut from the same cloth, with a wide range of scientific subjects covered.

July – Pink Life’s First Colour

July featured marine crocodile evolution, a dinosaur discovery from Northern China (Lingwulong shenqi) that defied logic, Utah’s latest armoured dinosaur, Spanish plesiosaurs and French gomphotheres. However, we were “tickled pink” to be able to write about the analysis of 1.1 billion-year-old cyanobacteria that led to the extraction of pink coloured pigments from ancient marine shales. The world’s oldest biological colour turns out to be pink: In the Pink! The First Colour of Life.

A Team of International Scientists Have Isolated the Oldest Known Biological Colour

Picture credit: Australian National University

August – DIY Taphonomy – (Make Your Own Fossils)

The beautiful summer weather continued into August and much of the UK faced drought conditions. However, fossil finds and prehistoric animal news stories did not dry up. Team members wrote about marine reptile discoveries in Queensland, a new nodosaurid from Mexico, Chinese alvarezsaurids, a challenge to the idea of aquatic spinosaurids, Scottish sauropods and toothy pterosaurs from the Late Triassic. It was an article on how a team of scientists had learned to mimic the fossilisation process, compressing millions of years into just 24-hours that really got our attention. After all, having a better understanding of how fossils form (taphonomy), will help to improve fossil interpretation: Do It Yourself Taphonomy!

September – Dickinsonia Definitely an Animal

September turned the spotlight on the ediacaran fauna and one of the most puzzling of all the bizarre life forms to have ever existed – Dickinsonia. A research paper finally put to rest (most probably), a long-standing argument about this disc-shaped organism. It was an animal. What sort of animal? This remains an area of some debate, but the 550-million-year-old Dickinsonia is now in the same Kingdom as ourselves (Animalia). Here is our article: Mysterious Dickinsonia Classified as an Animal.

A Fossil of the Enigmatic Dickinsonia – Finally Classified and Placed in the Animalia

Picture credit: Australian National University

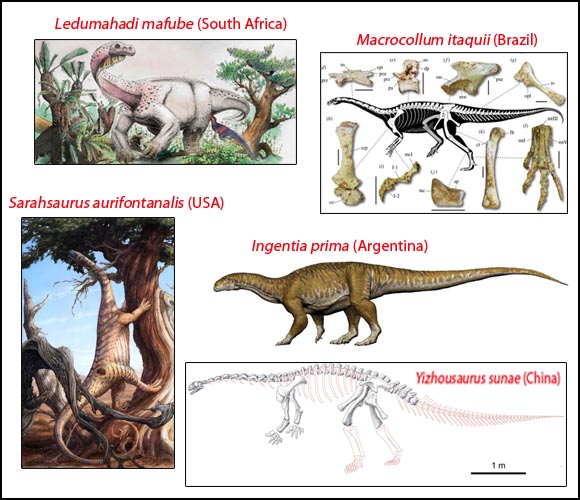

October – A Better Understanding of the Sauropodomorpha (Sarahsaurus et al)

This year, we have seen numerous scientific papers published relating to the evolution and dispersal of the Sauropodomorpha (the sauropods and their ancestral forms). For example, researchers from the University of Texas concluded that ancestors of North American, Early Jurassic sauropodomorphs, such as Sarahsaurus were essentially migrants. In China, a study of Yizhousaurus fossil material yielded new data on the evolution of long-necked dinosaurs. The announcement of the discovery of a monstrous Late Triassic sauropodomorph from Argentina (Ingentia prima), demonstrated that gigantism in the Dinosauria occurred earlier than previously thought.

Amongst all these amazing sauropodiform/Sauropodomorpha articles, we even managed to publish a feature on the oldest, long-necked dinosaur described to date – Macrocollum itaquii. October like much of the year, was dominated by the sauropods: The Ancestors of Sarahsaurus Probably Did Not Originate in North America.

Great Strides in Our Understanding of the Sauropodomorpha in 2018

Picture credit: Viktor Radermacher (Witwatersrand University), R T Müller et al, Jorge A. González, Brian Engh, Xiao-Cong Guo and Everything Dinosaur

2018 is likely to be remembered by many vertebrate palaeontologists as the year in which the evolution of the Sauropodomorpha began to make more sense.

November – Fresh Insight into the “Siberian Unicorn”

Our blog posts in November were dominated by news of new models and figures for 2019.

The weblog also covered elephant-sized Triassic dicynodonts, Oregon ornithopods, enantiornithine birds from Utah, ornithischian dental batteries, a new rebbachisaurid (Lavocatisaurus agrioensis), from Argentina and our work in schools. However, it was a feature on the enigmatic Elasmotherium, sometimes referred to as the “Siberian Unicorn” that stood out for us. A scientific paper published in November, revealed that the enormous Elasmotherium probably survived until as recently as 36,000 years ago. It was climate change that ultimately led to the demise of this beast, the paper on the relatively recent extinction of a member of the Rhinoceros family puts into focus the current plight of the remaining members of this once diverse and extensive family of hoofed mammals.

All extant members of the Rhinocerotidae face a very uncertain future.

To read about the extinction of Elasmotherium: Extinction of the “Siberian Unicorn” caused by Climate Change.

An Illustration of the “Siberian Unicorn” – Elasmotherium

Picture credit: Everything Dinosaur

December – Fuzzy Feathered Pterosaurs and the First New Ceratopsian of 2018

As the year drew to a close, the breadth and scope of the topic areas we attempted to cover did not diminish. Over the course of December lost Australian dinosaur toe bones, a new, dog-sized dinosaur from down-under (Weewarrasaurus pobeni), ichthyosaur blubber, new models and replica retirements all featured.

This month, we also wrote articles about a new Russian dinosaur (Volgatitan simbirskiensis) and featured a paper that demonstrated that the first flowering plants probably evolved at least fifty million years earlier than previously thought. Two articles we published stand out for us, firstly, on December 14th we produced an article on the ceratopsian Crittendenceratops krzyzanowskii, a new species of centrosaurine from Arizona. In the last twenty years or so, there have been an astonishing number of new horned dinosaurs described and named. Ironically, Crittendenceratops is the first (and only), new horned dinosaur to be named in 2018: A New Horned Dinosaur Species from Late Cretaceous Arizona.

A Life Reconstruction of Crittendenceratops krzyzanowskii

Picture credit: Sergey Krasovskiy

Secondly, our blog post from December 17th, featured the work of an international team of scientists who had identified four kinds of feather-like filaments on the fossils of pterosaurs: Are the Feathers About to Fly in the Pterosauria? If they are correct, then this suggests that either the Pterosauria evolved feathers as a form of convergent evolution separate from the Dinosauria, or, that feathers evolved many millions of years earlier than previously thought – in a common ancestor of the Dinosauria and the Pterosauria clades. Interesting times ahead for those palaeontologists that study flying reptiles.

Four Types of Feather-like Structures Identified in Chinese Pterosaurs

Picture credit: Chinese Academy of Sciences/Journal of Vertebrate Palaeontology

Our thanks to all our blog readers.

Visit the Everything Dinosaur website: Everything Dinosaur.

Leave A Comment