Late Permian Therapsid was Probably Venomous According to New Study

Euchambersia mirabilis was Probably Venomous

Detailed scans of the skull of the stem-mammal Euchambersia mirabilis supports a theory first proposed by the enigmatic Baron Franz Nopcsa ninety years ago, that this Late Permian creature was venomous. Scientists at the University of Witwatersrand (South Africa), concur with the Baron’s idea that this half-metre-long therapsid reptile known from the famous Karoo Supergroup, represents the earliest known venomous terrestrial vertebrate.

An Illustration of the Late Permian Therapsid Euchambersia mirabilis

Picture credit: Everything Dinosaur

For models and replicas of Palaeozoic tetrapods: CollectA Prehistoric Life Figures.

Euchambersia mirabilis and Baron Nopcsa

Baron Nopcsa was an Austro-Hungarian aristocrat who discovered and identified a number of dinosaurs and other prehistoric animals around the world. In 1933, during a trip to South Africa, he looked at the remains of a therapsid found a couple of years earlier by Robert Broom, the fossil was identified as a distant ancestor of today’s Mammalia. Nopcsa stated that the fossils probably represented an animal with a deadly bite.

Nopcsa declared that this was probably the earliest venomous species ever recorded. However, his theory couldn’t be confirmed or disproved because venom and venom glands don’t fossilise. A study of the skull and the upper jaw (maxilla) had shown that E. mirabilis had a huge, deep maxillary fossa (a hollow), associated with a ridged canine. To the Baron, this implied that Euchambersia possessed a specialised gland situated inside the maxillary fossa that was capable secreting venom down the ridged canine tooth into victims.

CT Scanning Technology Provides Support for Nopcsa’s Theory

A team of researchers from the Johannesburg-based university set out to scan the known fossil skulls of Euchambersia and to create detailed three-dimensional images. It seems that Baron Nopcsa was right, the 21st century technology supports the idea that the 255-million-year-old Euchambersia is indeed, the earliest example of a venomous terrestrial vertebrate known to science.

Some extant mammals produce venom, for example, the bizarre Australian Duck-billed platypus (a monotreme), but also amongst placentals there are venomous mammals too. With a stem-mammal probably being venomous, it puts forward a tantalising idea that in the past, all early mammal forms may have had venom, but as the synapsid lineage that was to give rise to modern mammals evolved, so the venom producing glands were lost.

Known from Only Two Fossil Specimens

The fossils that Baron Nopcsa studied back in 1933, represent a species that is only known from one other set of fossils. Both specimens were discovered in the same area, just a few metres apart close to the town of Colesberg (Northern Cape Province of South Africa). The second specimen was not found until 1966. One specimen is housed in the collection of the Natural History Museum London, the other is at the Evolutionary Studies Institute in Johannesburg.

A Closer View of One of the Euchambersia Skulls Used in the Study

Picture credit: University of Witwatersrand

CT Scans Provide Evidence

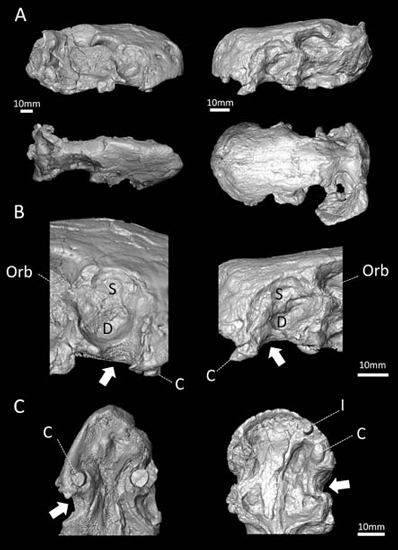

Each specimen was CT scanned at its respective institute, and the London data was sent to the researchers at the University of Witwatersrand. The three-dimensional models that the images were able to provide gave the scientists the opportunity to explore in great detail the internal structure of the upper jaw.

CT Scans Revealed New Details of Euchambersia Skull and Jaw Anatomy

Picture credit: PLOS One/University Witwatersrand

Lead author of the report, published in PLOS One, Dr Julien Benoit commented:

“We found that a wide, deep and circular fossa to accommodate a venom gland was present on the upper jaw and was connected to the canine and the mouth by a fine network of bony grooves and canals. Moreover, we discovered previously undescribed teeth hidden in the vicinity of the bones and rock, two incisors with preserved crowns and a pair of large canines, that all had a sharp ridge. Such a ridged dentition would have helped the injection of venom inside a prey.”

Dr Julien Benoit Holding One of the Skulls that was Scanned

Picture credit: University of Witwatersrand

Identifying Anatomical Adaptations in Euchambersia mirabilis

It seems that Euchambersia had anatomical adaptations which were compatible with venom production. The confirmation of the Baron’s theory strengthens the belief that pre-mammalian therapsids were very diverse and occupied a wide range of niches within Late Permian and Early Triassic ecosystems.

These ancient creatures, distantly related to our own species, diversified as herbivores and carnivores, large and small, burrowing and ground-dwelling species. As the earliest venomous species and a representative of this early wave of pioneering species, Euchambersia directly reflects the extraordinary adaptive capabilities of these mammalian forerunners.

The scientific paper: “Reappraisal of the Envenoming Capacity of Euchambersia mirabilis (Therapsida, Therocephalia) using μCT-scanning Techniques,” published in the on line journal PLOS One.

Everything Dinosaur acknowledges the assistance of the University of Witwatersrand in the compilation of this article.

Visit the award-winning Everything Dinosaur website: Everything Dinosaur Website.