Idaho State University Scientists Solve Spiral-Toothed Shark Puzzle

A team of researchers have got to the bottom of a fishy puzzle that had palaeontologists previously in a spin. Fossils of an ancient cartilaginous fish known as Helicoprion show a whorl of spiral, saw-like teeth but up until now scientists were unsure where on this prehistoric fish the teeth whorl was located. Was this strange toothed structure inside the jaw or outside, did it actually belong in the mouth at all, perhaps it formed part of a defensive structure located on the dorsal fin? After all, the fossil record does contain some remarkable fossils of sharks, for example, Stethacanthus from the Late Devonian with a large projection known as the “ironing board” on its back.

Prehistoric Fish

Using their unrestricted access to the Helicoprion spiral-toothed fossils at the Idaho State Museum of Natural History the research team were able to examine a number of beautifully preserved fossils. This museum has the largest public collection of Helicoprion teeth fossils in the world and a number of these specimens have been collected from Early Permian strata exposed in Idaho. The actual body shape of this large, prehistoric predator is open to speculation as since the skeleton of this animal was made of cartilage, very few fossils other than those of the strange teeth have been found. It had been thought that Helicoprion was a nektonic and very active predator, patrolling the water column in a similar way to a lot of extant shark genera.

Previously, scientists had thought that this creature was a type of shark, however, this new research links this 270-million-year-old fish to another group of fish with cartilaginous skeletons.

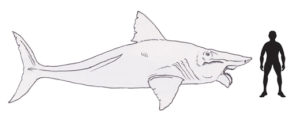

A Scale Drawing of Heliocoprion

As Everything Dinosaur prepares for the arrival of Haylee the Helioprion model from PNSO a scale drawing of this Permian fish has been commissioned. Picture credit: Everything Dinosaur.

Picture credit Everything Dinosaur

Helicoprion

A large number of Helicoprion fossils were subjected to intense examination and analysis including computerised tomography – a process whereby high-powered X-rays bombard a fossil and provide non-destructive, three-dimensional images that reveal hidden aspects of anatomical structure. One such fossil studied, measured over twenty-three centimetres in length and contained the remains of one hundred and seventeen individual, triangular teeth. However, unlike most of the other known Helicoprion fossil material, this specimen had preserved impressions which showed the placement of parts of the cartilage skeleton.

Using the detailed computer images that the CT scans produced the team were able to deduce that the spiral teeth were located at the back of the jaw, the teeth did not project forwards from the lower part of the mouth, nor was this structure located on another part of the fish. Dr Leif Tapanila of the department of Geosciences at Idaho State University and his colleagues have been able to clear up this mystery surrounding the whorl of teeth.

Tooth Whorl Analysis in Helicoprion

Helicoprion specimen IMNH 37899, preserving cartilages of the mandibular arch and tooth whorl. (a) Photograph and (b) surface scan of fossil. Picture credit: Tapanila et al in Biology Letters.

Picture credit: Tapanila et al

He stated:

“We were able to answer where the set of teeth fit in the animal. They fit in the back of the mouth, right next to the back joint of the jaw. We were able to refute that it might have been located at the front of the jaw.”

Studying the Wear Pattern

Analysis of the wear pattern on the teeth also provided the researchers with an insight into what this predator may have eaten as it swam in the Permian seas. It is unlikely that these teeth were used to crush hard bodied creatures such as shellfish or marine snails. It is more likely that Helicoprion tackled soft bodied members of the Phylum Mollusca such as cephalopods (squid and octopi).

A Scientific Paper

The paper, published in the prestigious academic journal “Biology Letters” provides further information on how the scientists think the jaws actually worked. The jaw was able to produce a rolling-back and slicing action, ideally suited to tackling soft and slippery prey. The research has also suggested that Helicoprion was not a type of shark, but that it is more likely closely related to the extant rat fish, making it a basal, but very specialised member of the Holocephalan group called the Euchondrocephali.

Dr Tapanila added:

“New CT scans of a unique specimen from Idaho show the spiral of teeth within the jaws of the animal, giving new information on what the animal looked like and how it ate.”

The teeth may be very shark-like with their triangular shape and serrated edges, but evidence from the CT scans indicates that Helicoprion should be classified as a Holocephalan.

The Idaho Fossil Specimen

The Idaho fossil specimen suggests an animal around 4.2 metres in length but other Helicoprion teeth fossils indicate fish that could have reached lengths in excess of 7 metres. The work of the scientists will form the basis of a new Helicoprion exhibit that is to open shortly at the Idaho Museum of Natural History.

It seems that this creature was a specialised predator from the end of the Permian onwards the top predator niches in the world’s oceans were to be mainly occupied by sharks, before the evolution of the larger Teleost fish challenged the shark’s dominant position.

Helicoprion and Prehistoric Fish Models

Those clever people at Safari Ltd introduced a Toob (a tube containing models), called “Prehistoric Sharks” a couple of years ago now. The models show different types of ancient cartilaginous fish including the likes of Stethacanthus and a model of Helicoprion. This set of ten prehistoric fish has proved popular and it is fascinating to see how the interpretation of Helicoprion by the design team at Safari Ltd matches up against the latest scientific data.

The Helicoprion Model from the “Prehistoric Sharks” Toob

Picture credit: Everything Dinosaur

The snout may be somewhat elongated and the body perhaps a touch more streamlined, that of an active predator in the mid water column but the front jaw does resemble quite closely the latest scientific interpretation.

Helicoprion Up Close

Picture credit: Everything Dinosaur

The morphology of this Early Permian predator may not be known but credit must be given to the design team at Safari Ltd for creating a replica that does have some similarities to the illustrations provided in the scientific paper. It remains uncertain whether this shark was an active, fast swimming hunter or whether it lived close to the sea floor and had a more sedentary habit, but at least the mystery regarding its remarkable dentition (teeth) seems to have been solved.

PNSO Helicoprion Replica

PNSO Haylee the Helicoprion replica. The stunning emerald eye on the model is reminiscent of the eye of a Chimaera such as the deep water Rabbit Fish (Chimaera monstrosa) to which Helicorprion is distantly related.

PNSO have released a superb replica of this iconic prehistoric fish. To view the range of PNSO prehistoric animal models and figures available from Everything Dinosaur: PNSO Age of Dinosaurs Models.

Everything Dinosaur acknowledges the assistance of a press release from Idaho State University in the compilation of this article.

The scientific paper: “Jaws for a spiral-tooth whorl: CT images reveal novel adaptation and phylogeny in fossil Helicoprion” by Leif Tapanila, Jesse Pruitt, Alan Pradel, Cheryl D. Wilga, Jason B. Ramsay, Robert Schlader and Dominique A. Didier published in Biology Letters.

Leave A Comment