Pterosaurs “Pole-Vaulted” to Become Airborne

New Study Suggests Large Pterosaurs Used Their Arms and Legs to Get off the Ground

A new study published in the open access and online journal PLoS One (Public Library of Science) suggests that the largest of the pterosaurs launched themselves into the air by using the powerful muscles of their legs and arms to push off from the ground, effectively pole-vaulting over their wings. Once airborne these huge creatures could fly long distances using air currents to help them stay aloft with the minimum of effort, just like many large birds do today.

Pterosaurs

Pterosaurs, otherwise known as flying reptiles, are an extinct group of reptiles that evolved in the Triassic and survived until the very end of the Cretaceous. Their wings were formed out of skin that stretched from the body over the forelimbs and along an elongated fourth finger that acted as a supporting strut for the wing membrane. A number of unrelated reptile groups had taken up gliding since the Permian Period, most likely to exploit food resources in trees and to escape from predators. An example of an early glider would be a genus like Kuehneosaurus. However, active flight in vertebrates, that is, being able to control movements in the air under the power of their own muscles, was first seen in the pterosaurs. For millions of years, these highly specialised archosaurs, had the skies to themselves. With the evolution of the birds, slowly but surely this once spectacular and diverse group of reptiles went into decline.

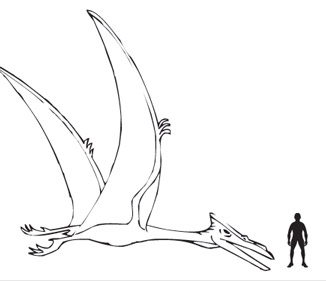

The last types of pterosaurs to evolve were huge. The very last kinds of pterosaur that survived into the Maastrichtian faunal stage of the Cretaceous belonged mainly to a family of flying reptiles known as the azhdarchids – huge creatures like Quetzalcoatlus northropi with a wingspan in excess of 12 metres. Scientists had puzzled for many years over how these very large and quite heavy creatures were able to launch themselves into the air in order to fly.

An Illustration of a Late Cretaceous Azhdarchidae Pterosaur – Quetzalcoatlus northropi

Picture credit: Everything Dinosaur

The Azhdarchidae Pterosaurs

Indeed, a recent theory regarding the largest of the Azhdarchidae, suggested that these reptiles, some of which were as tall as a modern giraffe, did not fly very much at all. Instead, they roamed the Cretaceous plains, like Secretary birds; stalking small animals in the undergrowth and snatching up unwary creatures, including baby dinosaurs with their long, sharp toothless beaks.

To read an article on this theory: Getting Stalked by a Flock of Quetzalcoatlus.

The research was conducted by Dr Mark Witton, a palaeontologist from the University of Portsmouth, a specialist in pterosaur evolution and flight mechanics. He was aided and assisted by Dr Michael Habib from Chatham University (Pennsylvania). The two scientists examined the bones of giant pterosaurs to see if they could work how these bizarre creatures could have become airborne. They concluded that these animals may have literally pole-vaulted themselves up into the air.

A Pterosaur “Pole-Vaulting” into the Air

Picture credit: Dr Mark Witton

Another, top class illustration by Dr Mark Witton shows a pterosaur, in this instance a member of the Pteranodontidae family, a Pteranodon longiceps taking to the air, by springing off the ground using its immensely strong arms.

Pterosaur Fossils

Many pterosaur fossils have been found in strata laid down in what was a marine environment. This suggest that these particular flying reptiles lived close to the sea. They could have launched themselves into the air by leaping from a cliff face, in the same way that many seabirds do today. However, for those fossils of large pterosaurs found in non-marine strata, how they would have become airborne remained more problematical. A thorny problem that now the UK and USA based researchers suggest they have a solution to.

They examined the fossil evidence and avoided trying to compare and contrast the pterosaurs with Aves (birds).

Dr Witton commentated:

”Most birds take off either by running to pick up speed and jumping into the air before flapping wildly, or if they’re small enough, they may simply launch themselves into the air from a standstill. Previous theories suggested that giant pterosaurs were too big and heavy to perform either of these manoeuvres and therefore they would have remained on the ground.”

However, if birds are disregarded, and the fossil evidence examined with an emphasis on anatomical features, wing proportions and muscle attachment scars on the pneumatised Pterosaur bones, then it becomes clear that these flying reptiles would have achieved flight in a very different way compared to their feathered counterparts.

Dr Witton stated:

”These creatures were not birds, they were flying reptiles with a distinctly different skeletal structure, wing proportions and muscle mass. They would have achieved flight in a completely different way to birds and would have had a lower angle of take-off and initial flight trajectory. The anatomy of these creatures is unique.”

The two doctors propose that pterosaurs with up to 50 kilogrammes of forelimb muscle, could easily have propelled themselves into the air despite their huge size and considerable weight.

Previous theories have asserted that the largest of the pterosaurs could have been six metres in height with a wingspan of up to 12 metres but the researchers argue that five metres high with a 10 metre wingspan would have been perhaps more accurate.

Commenting on the strength of the forelimbs, Dr Witton said:

”The size of the flight muscles in a giant pterosaur would be incredible; they alone would be up to 50 kg (110lbs) and account for 20% of the animal’s total mass providing tremendous power and lift.”

Dr Habib added:

”Scientists have struggled for decades to figure out how giant pterosaurs could become airborne, and some recent proposals have simply assumed it must have been impossible. But they may have approached the problem from the wrong end, instead of taking off with their legs alone, like birds, pterosaurs probably took off using all four of their limbs.”

This method of launching into the air, would be unique to the pterosaurs, if true, it might help to explain how they were able to grow to such huge sizes, with many genera of pterosaur far bigger in size than the largest flying birds today.

Dr Habib concluded:

”By using their arms as the main engines for launching instead of their legs, they use the flight muscles, the strongest in their bodies, to take off and that gives them potential to launch much greater weight into the air. This may explain how pterosaurs became so much larger than any other flying animals known.”

The researchers examined anatomical aspects of large pterosaur skeletons calculating the relative strength of the bones and assessed the animal’s likely performance when “flap gliding” – the form of flight most likely to have been undertaken by these large creatures. The team concluded that not only could flying reptiles the size of a bus, fly, they could do so extremely well and probably travelled vast distances crossing oceans and continents. Recent studies of endocasts of pterosaur brains and other elements related to skull morphology suggest that these animals had keen senses and a great sense of balance – just what is required for active, powered flight.

The scientists found that it was unlikely that the flying reptiles would need to flap continuously to remain aloft once airborne. Instead, these creatures would flap powerfully in short bursts with their large size allowing them to achieve rapid cruising speeds.

Commenting on this aspect of their study, Dr Witton said:

”Pterosaurs had incredibly strong skeletons, for their weight, they are probably amongst the strongest ever evolved. And, unlike birds, where the wings become relatively weak as they grow in size, those of pterosaurs do the opposite: they become stronger. As pterosaurs became larger, they reinforced their wings and expanded their flight muscles to ensure they could keep flying.”

A fascinating insight into how, pterosaurs could perhaps have taken off. Whilst we at Everything Dinosaur, agree that many flying reptiles living in marine environments may have used cliffs to launch themselves into the air, how those pterosaurs that lived inland became airborne has remained a mystery. Could this new theory provide the explanation?

We do have our own way of making pterosaurs fly. When we were working on the publicity shots for the new Pteranodon longiceps replica from CollectA we were asked to try to show this model flying low over the other models in the series. The shot was achieved by the use of a strategically placed hand, some fishing line and photo-shop.

Our Pterosaur “Takes to the Air”

Picture credit: Everything Dinosaur

To view the CollectA range of not-to-scale prehistoric animal models: CollectA Prehistoric Life Models and Figures.