Dinosaur Biting Techniques – Something to get your Teeth Into

Theropod Dinosaurs – A Range of Biting Styles

Bristol University researchers examine dinosaur biting techniques. A subject area for the eager students to get their teeth into.

A new study into the biting styles and the forces that could be generated as a dinosaur bit into its prey has been published in the scientific journal “The Proceedings of the Royal Society – Biology”. This study carried out by researchers at the University of Bristol, identifies at least four different biting techniques, it seems some dinosaurs were fast “nippers” whilst others had slower but more powerful bites.

The study focused on the bites of theropod dinosaurs. Theropods (Theropoda) were bipedal and mostly meat-eating although a number of forms evolved to exploit different environmental niches resulting in a non-carnivorous diet in some cases. The research shows that following a careful analysis of tooth position, tooth size, length of the jaws and the shape and design of theropod dinosaur skulls, four basic biting techniques were identified with a trade-off between bite strength and the speed of the bite.

Dinosaur Biting Techniques

The study indicates that meat-eating dinosaurs ranged from weak biters but fast biters such as the dromaeosaurs (Velociraptor, Deinonychus etc.) and the strong, more efficient biters such as the last of the tyrannosaurs (Tyrannosaurus rex).

The author of this new research, Manabu Sakamoto, a scientist in the Department of Earth Sciences at the University of Bristol (England), examined the biting characteristics of 41 different theropod dinosaurs, from Triassic, fleet-footed meat-eaters such as Coelophysis to the mighty allosaurs and tyrannosaurs.

Not surprisingly, the study shows that tyrannosaurs and allosaurs inflicted the most damaging, efficient bites. These large predators probably relied on an swift ambush attack, then withdrawing to let their victim weaken through shock and blood-loss. Tyrannosaurus rex had one of the best developed senses of smell known to science. It could have used this superb sense of smell to track down its victim, even though the hapless animal may have wandered many miles from the scene of the attack.

The ceratosaurs, are also revealed as being efficient strong, biters. Again, this is not surprising, as dinosaurs from the Ceratosaurus genus (Ceratosaurus sp.) have some of the largest teeth in proportion to the size and width of the jaws in the reptilian fossil record. Their dagger-like teeth seem almost too big for their own mouths. One Ceratosaurus species Ceratosaurus ingens is only known from fossils of huge teeth that have been found. The teeth indicate that this particular species of ceratosaurid may have been one of the biggest carnivores around during the Late Jurassic.

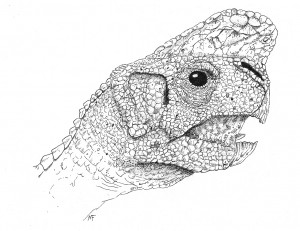

Ceratosaurus – Big Teeth = Fearsome Bite

Picture credit: Everything Dinosaur

The picture above shows a scale drawing of a typical ceratosaurid.

Interestingly, the oviraptorids come out very favourably in terms of the efficiency of their bites in this new study. Oviraptorids were very bird-like dinosaurs, not only in their general build but also as a result of the presence of a beak. Some scientists have suggested that this particular family of dinosaurs should not be classified as Dinosauria but as members of the Aves (birds).

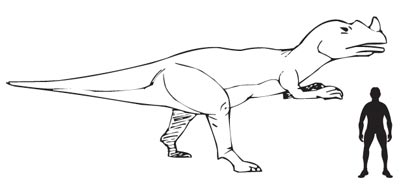

Illustration of a Typical Oviraptorid

Picture credit: Mike Fredericks

Everything Dinosaur stocks a wide range of theropod dinosaur figures and replicas: Theropod Dinosaur Models.

Studying Oviraptorids

Scientists are uncertain as to what sort of food oviraptorids ate. The jaws seem to have evolved for a crushing action, perhaps these Cretaceous animals fed on nuts or hard fruit. It has even been suggested that oviraptorids fed on shell fish, their strong jaws would have easily cracked open clams and the shells of other molluscs.

The research from the Bristol team shows that even though some dinosaurs did not have as many teeth as others, the teeth they did possess did a very efficient job.

Manabu Sakamoto commented on the efficiency on the bites of allosaurs and tyrannosaurs, he stated:

“These dinosaurs have consistently high efficiency in biting along the entirety of their relatively short tooth rows.”

The bite strength of the theropod dinosaurs studied was calculated by determining the ratio between the size of the muscles in the jaws and the biting force they could potentially generate. This is termed “the mechanical advantage” and unlike previous studies into dinosaur bite forces, the Bristol University researchers calculated the bite strength for each tooth and biting position in the jaws.

Sakamoto discovered that the most primitive type of biting belonged to dinosaurs such as Herrerasaurus, Carcharodontosaurus, and Ceratosaurus. Their back teeth did much of the work.

One of the most bizarre biting styles belonged to the coelophysoid dinosaurs, animals such as Coelophysis and Syntarsus. These fast running, relatively small, meat-eaters were widespread during the Late Triassic and Early Jurassic. Typically, they had long necks and small skulls with narrow jaws. Coelophysids could bite with a great deal of force at the back of their mouths, but their front teeth were limited to a really weak and fast bite. These particular dinosaurs probably preyed on smaller, fast moving prey such as lizards and other dinosaurs, but their long necks and narrow muzzles may have permitted them to scavenge the kills from larger meat-eaters.

The final type of carnivorous dino bite belonged to what Sakamoto called “the ostrich-like dinosaurs,” such as Velociraptor (dromaeosaurs). Typically, these dinosaurs had more teeth in their jaws when compared to the larger allosaurs and tyrannosaurs.

Manabu commented on the findings:

“These dinosaurs have consistently low efficient biting across their tooth rows so they have relatively weak bites. But, in effect, this also means that they have relatively fast biting speeds.”

He added that the research into the bite force and technique of Archaeopteryx (A. lithographica), showed that this ancient bird bit in a similar style to the Velociraptors.

Various Biting Styles

Another component of the study involved testing whether or not closely related dinosaurs bit in similar ways. For the most part, this was true, providing evidence that the various biting styles were inherited, evolved behaviours.

However, there were one or two exceptions to this rule thrown up by the study. The parrot-like oviraptorids and the therizinosaurs (Scythe Lizards), a bizarre type of theropod dinosaur that adapted to a vegetarian diet and are believed to have filled a “sloth-like” niche in Northern Hemisphere ecosystems; did not have predictable biting styles based on their evolutionary history. Although, relatives of these two groups of dinosaurs were weak, yet fast biters, the oviraptosaurids and the therizinosaurids were highly efficient, strong biters.

Commenting on this aspect of the research Manabu suggested:

“A possible explanation is that the ancestral stock of this group underwent adaptive evolution and filled an open ecological and functional niche.”