Coelacanth caught of the island of Zanzibar

Coelacanth caught of the island of Zanzibar

Reports from African news agencies state that fishermen in northern Zanzibar have caught a Coelacanth. Zanzibar is the largest of a small group of islands of the coast of Tanzania. Coelacanths are caught occasionally in the nets of fishermen in African waters and a catch of this living fossil usually attracts the attention of the local media.

Apart from the six species of lungfish, the Coelacanth is the only other survivor of the fleshy-finned fish group of fishes that first evolved in the Devonian (410 – 355 mya). Coelacanths were thought to have died out at the end of the Cretaceous period with their fossil record disappearing around 70 – 65 mya, however, a trawler working off the coast of South Africa in 1938 was to turn scientific thinking on its head.

Trawling off the Chalumna river estuary, Hendrik Goosen captain of the trawler Nerine, and his crew noticed a bizarre looking fish amongst their haul in what had been just another day fishing in the Indian Ocean. As the trawler landed its catch word spread about this strange creature and on the 22nd December 1938, Marjorie Courtney-Latimer, the curator of the East London museum in South Africa was notified.

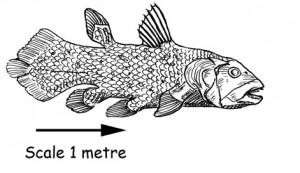

The fish was 5 feet long (1.5 metres) and weighed 127 pounds (58 kgs) and whilst it was still alive it was ferocious enough to attack anyone and anything that came within its reach. The strange three-pronged tail and the lobe shaped fins which were on fleshy stalks led Miss Courtney Latimer to conclude that this was a Coelacanth, identical to ones found in the fossil record but believed extinct.

This genus of coelacanth was named Latimeria chalumnae in honour of Miss Courtney-Latimer and the location where it was first found.

For prehistoric animal models including models of Coelacanths and other amazing creatures: Dinosaur and Prehistoric Animal Models.

Since that fateful day a number of coelacanths have been caught (the average is about a dozen per year). Most of the catches are from the Comoro island off Madagascar, the locals use the coarse-scaled skin as sand paper, roughening the inner tubes of their bicycle tyres when they want to mend a puncture.

Despite having been known to science for the best part of 70 years we still know very little about these fishes. They live on rocky reefs and caves between 500 – 2300 feet (150 – 700 metres) deep, are sluggish and nocturnal. It is believed they can grow to over 6 feet in length (2 metres) and are a metallic blue with white spots when seen in their natural environment.

In 1998, the Coelacanth once again shocked the scientific world. A marine biologist, Mark Erdman, on honeymoon on the Indonesian island of Menadtua discovered a Coelacanth on sale at the local fish market. Tests have revealed that the Coelacanths off Indonesia are genetically different from the African Coelacanths and that these fish split from the African population some 6 million years ago. How a group of them ended up off the islands of Indonesia is still unknown, what is more no one knows where else in the world Coelacanths may lurk. Hopefully, there are some more colonies out there as estimates from the Coelacanth Rescue Mission (an organisation dedicated to study and conservation of these animals), estimates that there are less than 1,000 left. There are more Black Rhinos in the world than Coelacanths, this is why this living fossil has been afforded protection under CITES (Convention on International Trade of Endangered Species of Wild Fauna and Flora).