Giant Seabird with a Toothy Grin – Pelagornis chilensis

Soaring over the skies of what is now Chile some 10 million years ago was a huge seabird, unlike any found today, a giant, with a wingspan of approximately 5 metres and a beak full of sharp, pointed “pseudo teeth”. This large pterosaur-sized creature has been named Pelagornis chilensis and a full paper on this saw-toothed seabird appears in the latest edition of the scientific publication “The Journal of Vertebrate Palaeontology”.

Prehistoric Seabird

Fossils of these strange birds ascribed to the genus Pelagornis have been found at a number of Tertiary aged sites, scientists believe that these birds evolved sometime in the Late Palaeogene and survived up until the end of the Pliocene epoch. The bones of these birds were extremely light and delicate and most of the specimens found to date are badly crushed and very little articulated material is known. However, this new South American species has been identified based on an “exquisitely and exceptionally preserved” fossil specimen according to co-author of this study, David Rubilar of the Museo Nacional de Historia Natural in Santiago (Chile).

A Super-soaring Prehistoric Bird

The publication of this paper on this super-soaring prehistoric bird comes at an important time for the museum, as on Tuesday 14th September the Museum celebrated 180 years of scientific work and curation, making this establishment older than the Natural History Museum in London. The phylogeny (the development or evolution of a particular group of organisms), of these “pseudo-toothed birds” is uncertain, most scientists associate them with the Albatrosses or Pelicans, it is hoped that this new fossil material will help palaeontologists to learn more about the taxonomy of these creatures and their relationships with modern extant Aves.

An Artist’s Illustration of P. chilensis

Picture credit: Carlos Anzures

Pelagornis chilensis

The specimen includes the largest and most complete fossil bird wing yet discovered, the fine grained, sandstone strata in the north of Chile where the fossil was found could yet yield more information about these strange and enigmatic birds. The tooth-like structures in the jaws are not teeth, but adaptations of the beak that permitted these seabirds to catch and hold slippery fish and squid in their beaks. Birds lost their reptilian teeth as a result of natural selection, adapting to a need to have lighter skeletons to enable more efficient flight.

The likes of Pelagornis evolved originally from birds with normal beaks, but the “pseudo-teeth” and the albatross-like skeletons suggest a sea-going lifestyle and hunting fish and other slippery creatures out at sea.

Previous fossils of Pelagornis have been badly crushed making it difficult to estimate wingspans, but the superb preservation of this particular specimen has led scientists to confidently estimate that this species had a wingspan of seventeen feet or more, nearly 50% bigger than the wingspan of most modern Albatross’s. When on the ground, these birds would have stood nearly 1.25 metres tall, about the size of a six-year-old child.

A Close up of the “Pseudo Teeth” in the Beak

Picture credit: S. Tränkner, Forschungsinstitut Senckenberg

The picture above shows the robust and powerful beak of P. chilensis. The “pseudo teeth” superficially resemble the teeth found in a number of rhamphorhynchids, a group of pterosaurs which scientists believe were also mainly fish-eaters. As the fossil skeleton is structurally similar to a modern albatross’s, studying the albatross may help scientists to understand the likely habits and behaviours of this extinct leviathan. Note the large orbit (eye socket), in the skull, an indication that these birds had large eyes and probably excellent eyesight.

More fossils might be unearthed soon, as David Rubilar commented:

“The fossils in this [sandstone layer] are abundant… probably we will find more and more complete specimens in the future.”

An Extremely Successful Group of Birds

Estelle Bourdon, a researcher with the American Museum of Natural History (New York), although not directly involved with this particular study, stated that these type of birds were extremely successful and seemed to have existed for many millions of years as a group. Fossil evidence suggests they evolved in the early Eocene Epoch, went onto establish themselves worldwide and finally went extinct at the end of the Pliocene Epoch.

Perhaps, these creatures filled the ecological niche that was vacated with the extinction of the last of the pterosaurs at the end of the Mesozoic.

Lead author, Gerald Mayr of the Forschungsinstitut Senckenberg (Germany) commented:

“Although they would have looked like creatures from Jurassic Park, they’re true birds and not flying reptiles. In fact, it is possible some of the the last living members of P. chilensis existed at the same time as the earliest human ancestors in Africa.”

The research team have concluded that P. chilensis was probably a glider, as the skeleton does not permit extensive flapping movement of the wings.

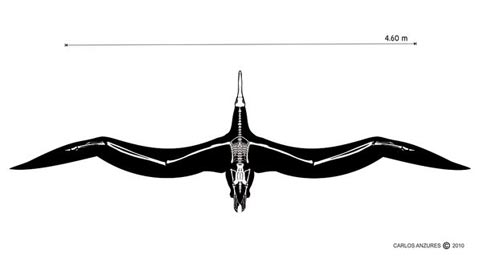

An Artist’s Illustration of the Skeletal Structure of P. chilensis

Picture credit: Carlos Anzures

The artist’s rendering shows the bird’s skeleton and the wingspan, aproaching an impressive five metres. An analysis of the arm bones shows that this bird could not rotate its wings to flap and provide lift, the research team have concluded that rather like Andean Condors today, these creatures simply “opened their arms” to take to the air, catching updrafts rising from hills and other geological features to become airborne.

Just like many modern, large seabirds Pelagornis chilensis could probably have glided for many hundreds of miles with a great efficiency of effort.

The researchers have compared the arm bones of this new specimen to the bones of Argentavis magnificens, an extinct Condor whose fossils have been found in Argentina. With a wingspan in excess of 8 metres, it is A. magnificens that currently holds the world record for the largest known flying bird.

However, the arm bone of P. chilensis is nearly 40 percent longer, so co-author David Rubilar is optimistic that larger specimens of P. chilensis could challenge this record. He pointed out that as A. magnificens probably had longer feathers it retains the world record for the largest flying bird known to science – at least for now.

For us at Everything Dinosaur, it is fascinating to note how the Aves radiated after the Cretaceous extinction event. This Order diversified and exploited a huge number of environmental niches. For example, it can be argued that these huge gliders replaced the fish-eating pterosaurs and other types of bird, such as the members of the Phorusrhacidae {thanks for the correction} (Terror Birds) evolved into large, cursorial predators replacing the theropods.

For replicas and models of prehistoric animals including prehistoric birds: Prehistoric Animal Models and Extinct Birds.

Surely “Phorusrhacidae”

Thanks for the correction, we have altered the article accordingly, our mistake, we took the notation from information picked up at the Museo Paleontological Egidio Feruglio in Argentina. Think the error occured due to problems with translating the Spanish text and the spelling mistake was not picked up in our correspondence.