News stories and articles that do not necessarily feature extinct animals.

The World’s Largest Bird Ever!

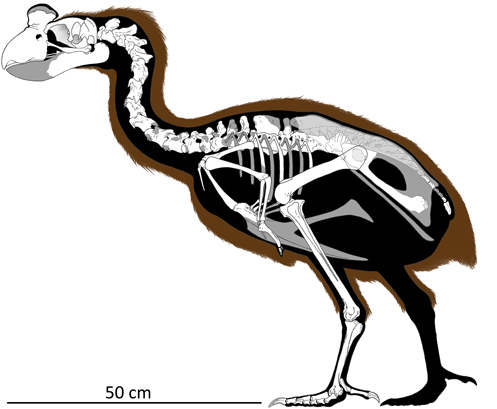

Vorombe titan – The Biggest Bird That Ever Lived

Scientists writing in the open access journal “Royal Society Open Science” have undertaken the first taxonomic revision for a very long time of the enigmatic family of giant, flightless birds, the “Elephant Birds”, that once roamed Madagascar. In the first detailed study into the Aepyornithidae for fifty years, the research team concluded that their taxonomy is in fact spread across three genera and at least four distinct species. Emerging out of this revision is Vorombe titan (meaning ‘big bird’ in Malagasy and Greek), the largest avian described to date.

Vorombe titan

V. titan may have lived as recently as 1,000 years ago and although standing more than three metres high and tipping the scales at an estimated eight hundred kilograms, this giant was relatively harmless, feeding on fruit, nuts and leaves.

At Around 3 Metres Tall and Weighing 800 Kilograms Vorombe titan is the Biggest of the Aepyornithidae

Picture credit: Jaime Chirinos

Researchers at the international conservation charity, the Zoological Society of London’s Institute of Zoology, have used complex statistical analysis to reorder the Aepyornithidae, discovering unexpected diversity in these Madagascan birds.

Complicated Taxonomy

The first scientific assessments of the “Elephant Birds” took place in the 1850s and species and genera assignment was based on comparative analysis, measurements and observed differences between fossils and bone specimens. It had previously been suggested that up to fifteen different species made up the Aepyornithidae, assigned to two genera (Aepyornis and Mullerornis). The scientists in this new study, coupled comparative analysis techniques familiar to 19th century anatomists with the latest multivariate cluster analysis and Bayesian statistical processes to re-examine these large-bodied ratites.

Using specimens from museums all over the world, the team identified three genera and at least four distinct species, as well as confirming that Vorombe titan is the biggest bird species known to science.

The World’s Largest Bird

The first species to be described, Aepyornis maximus, had been considered to be the world’s largest avian. However, in 1894, British scientist C.W. Andrews described an even larger species, Aepyornis titan, but this idea was controversial, the specimen ascribed to this new species – A. titan being thought by many scientists and academics to represent an unusually large example of A. maximus.

This new study establishes enough unique characteristics in the material associated with A. titan to conclude that it is, indeed, a separate species. The size, morphology and robust nature of its bones are so different from all other members of the Aepyornithidae, that this specimen has been placed in its own genus and named Vorombe titan.

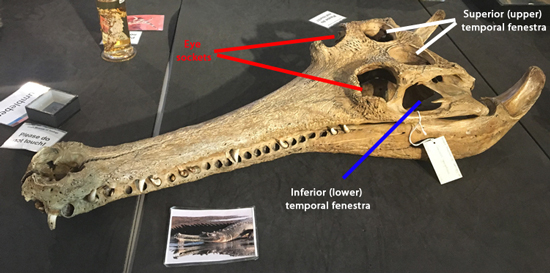

The Robust Femur of V. titan

Picture credit: Royal Society Open Science

Lead author of the study, Dr James Hansford (Zoological Society of London’s Institute of Zoology) explained:

“Elephant birds were the biggest of Madagascar’s megafauna and arguably one of the most important in the islands evolutionary history, even more so than lemurs. This is because large-bodied animals have an enormous impact on the wider ecosystem they live in via controlling vegetation through eating plants, spreading biomass and dispersing seeds through defecation. Madagascar is still suffering the effects of the extinction of these birds today.”

Helping to Understand the Evolution of a Unique Island Community

Co-author Professor Samuel Turvey (Zoological Society of London’s Institute of Zoology), added:

“Without an accurate understanding of past species diversity, we can’t properly understand evolution or ecology in unique island systems such as Madagascar or reconstruct exactly what’s been lost since human arrival on these islands. Knowing the history of biodiversity loss is essential to determine how to conserve today’s threatened species.”

This research links and clarifies the 19th century research with the very latest machine learning and Bayesian clustering statistical techniques, helping to solve a taxonomic muddle. With a better understanding of these extinct avian megafauna scientists will learn important lessons about the impact extinctions have on island communities.

The revelation that the biggest of these birds was forgotten by history is just one part of the remarkable story of the “Elephant Birds”.

The scientific paper: “Unexpected Diversity within the Extinct Elephant Birds (Aves: Aepyornithidae) and a New Identity for the World’s Largest Bird” by James P. Hansford, Samuel T. Turvey published by the Royal Society Open Science.

Visit the Everything Dinosaur website: Everything Dinosaur.