Wareolestes rex – Uniting English Teeth with a Scottish Jawbone

This month has seen the publication of a scientific paper on one of the lesser known animals of the Middle Jurassic, a very distant ancestor of us and one that roamed the land that we now know as the United Kingdom. The fossil collection attributed to the morganucodontan Wareolestes (W. rex), an animal named from four isolated teeth found in Oxfordshire (England), has increased with the description of a partial jawbone (left dentary), complete with several teeth.

Writing in the publication of the Palaeontological Association, the researchers from Oxford University and the National Museums of Scotland, conclude that this animal had milk teeth, as adult teeth were identified that had not yet erupted through the jawline. This means that this little mammaliaform (close to a true mammal but not quite), was a juvenile and the jaw fossil indicates that Wareolestes replaced its teeth once, just like humans, dogs, cats, horses and many other types of extant mammal.

An Illustration of the Head of Wareolestes rex

Picture credit: Elsa Panciroli

In addition, the pattern of tooth replacement reflects an important stage in mammalian evolution and is linked to the production of milk to feed offspring. This discovery marks the first time that mammaliaform tooth replacement has been identified from Scottish fossil material.

Jawbone from the Isle of Skye

The two-centimetre-long jawbone was found on the Isle of Skye (Kilmaluag Formation), in rocks that were laid down some 165 million years ago, when this part of the world consisted of tropical islands surrounded by a warm shallow sea (Bathonian faunal stage). The Middle Jurassic was an important time for mammalian evolution, unfortunately, there are very few fossil bearing exposures around the world that record evidence of life on our planet during this important period. The Isle of Skye is one of these locations, along with a handful of other places including the western United States.

To read more about Scotland’s Mid Jurassic heritage: What Does Scotland Have in Common with Wyoming?

Linking English Teeth to a Scottish Jaw

The teeth and the newly described jawbone, although tiny by the standards of most dinosaurs, the dentary of Wareolestes is about as big an average sized tooth in the lower jaw of Megalosaurus (M. bucklandii), tells palaeontologists that Wareolestes was quite big for a mammaliaform. Wareolestes grew to be around the size of a pet guinea pig, not massive, but most of the Middle Jurassic mammaliaforms were not much bigger than shrews.

Wareolestes rex was named and described from those few isolated teeth found in Oxfordshire. Controversy surrounded the first tooth to be found, the holotype. Scientists were not sure whether the tooth represented a tooth from the upper (maxilla) or lower jaw (dentary), they were not sure from which side of the mouth the tooth came from. An analysis of the holotype tooth with the newly described Scottish jawbone clarifies the situation. The original tooth from the Kirklington mammal beds in Oxfordshire came from the left side of the lower jaw (dentary).

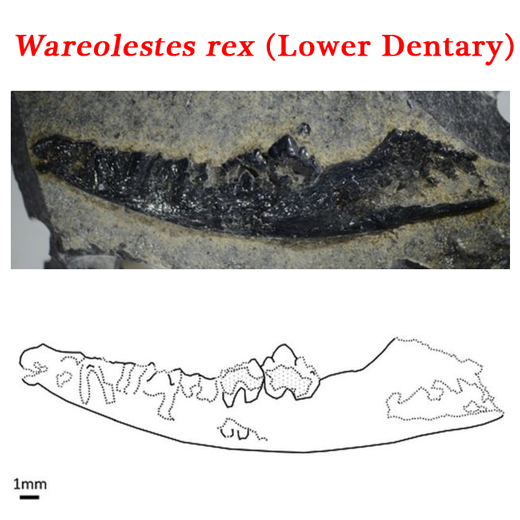

The Fossil Jaw and a Line Drawing

This little fur-covered animal, may have been nocturnal, a strategy that would have helped the guinea pig-sized Wareolestes avoid predators – crocodylomorphs and theropod dinosaurs for example. Like other morganucodontans, it was probably insectivorous. Careful CT scans and the creation of three-dimensional fossil images, allowed the English and Scottish-based researchers to identify the unerupted replacement teeth in the jaw. Had this Wareolestes perished just a few weeks later, then it is very likely that the adult teeth would have been in place and scientists would not have had confirmation of the diphyodont (two sets of teeth), nature of this little beastie.

The Specialised Teeth of Mammals

Mammals have specialised teeth, canines, incisors, molars and such like. Reptiles in contrast, have dentition that tends to be more homogeneous (all similar shapes). Wareolestes had teeth very similar to those of a modern mammal. This animal had “milk” teeth which were replaced by “adult” teeth as the animal grew. It can be inferred from this that adult females looked after and nurtured their young. Milk may have been secreted from modified pores for their offspring to lap up. There may have been small grooves or channels in this patch of skin with the milk pore, to help the liquid pool and collect so that the baby Wareolestes could feed.

This is an exciting discovery and we are looking forward to hearing more about fossil finds from the field work on the Isle of Skye. Researchers from Oxford University (England) and the National Museums of Scotland (Scotland), have found a jawbone fossil (Scotland) that solves a mystery surrounding some isolated teeth found decades earlier in England. The story has a sense of closure about it, just like the fitting cusps and crowns associated with those specialised teeth of mammals. However, we suspect that the dedicated team behind this particular piece of research will publish more papers about Middle Jurassic fossil finds, we can’t wait to get our teeth into them.

Leave A Comment